By Alexander Laing '25. New York & Boston: Duell, Sloan andPearce & Little, Brown, 1955. 524 PP. $4.95.

This is the tale of the adventurous life of Jonathan Eagle, who in 1786 came by sea as a nameless young orphan to Stonington, and soon returned to an element of which he was ever to be more a native than he was of the old Connecticut port. Young Jonathan is captured at sea by the Barbary pirates, courts a Liparian contessa while himself a slave in Algiers, voyages to the South Seas and resists the charms of willing dusky women, becomes deeply involved in the French Revolution in Guadaloupe and in Toussaint L'Ouverture's slave rising in Haiti, and finally returns, badly compromised, to an America torn between the opposing forces of Republicanism and Federalism, to be saved in the end by the steadfast love of a Stonington girl and the shrewd wits of her highly Yankee father.

It will surprise no one who knows Alex Laing that this is no mere adventure story, though Jonathan runs the gamut of all the adventures of Yankee seamen of the day, but is also a novel of political ideas. The book might have been called The Education ofJonathan Eagle, for it dramatically illustrates the early historical work of the author of TheEducation of Henry Adams, who also compiled the Documents Relating to New England Federalism and the great History of theUnited States. Unlike Adams' history, however, Jonathan Eagle ends in 1801 with the triumphant defeat of reactionary Federalism by the progressive Republican forces led by Thomas Jefferson.

As a sea story and a novel of adventure, this is a first-rate book, although one regrets a certain catering to the tradition of best sellerdom in matters of sex and sadism. As a novel of ideas it is perhaps somewhat less successful, for the sections devoted to the Federalist Republican conflict do not come off quite as well as the earlier ones, in which the author was more concerned with telling a tale than arguing a case. The analogies between Jonathan's search to discover "What is freedom? What is it, to be an American?" and the contemporary concern with the survival of freedom in another age of fear of foreign conspiracy against the nation are sometimes labored, with all the Federalists except two drawn in black and all the Republicans, if not in white, at least as the children of the Enlightenment.

But Johnathan Eagle is a useful tract for the times, as well as a stirring novel. It is sometimes reassuring to know that it has happened here before, and that the Republic survived.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom Flying Wedge to "T"

October 1955 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45, SPORTS EDITOR -

Feature

Feature"Not So, Brothers and Friends"

October 1955 By JOHN FINCH, PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH -

Feature

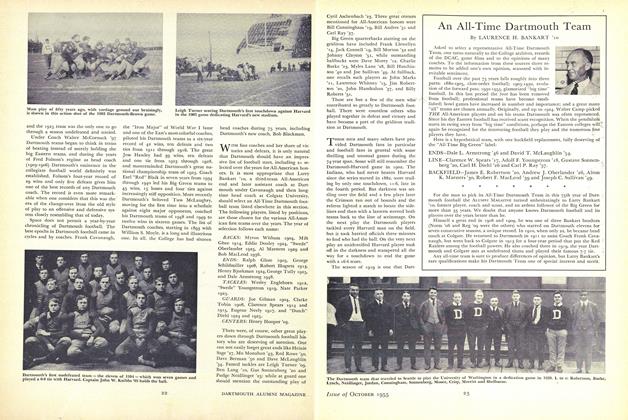

FeatureAn All-Time Dartmouth Team

October 1955 By LAURENCE H. BANKART '10 -

Feature

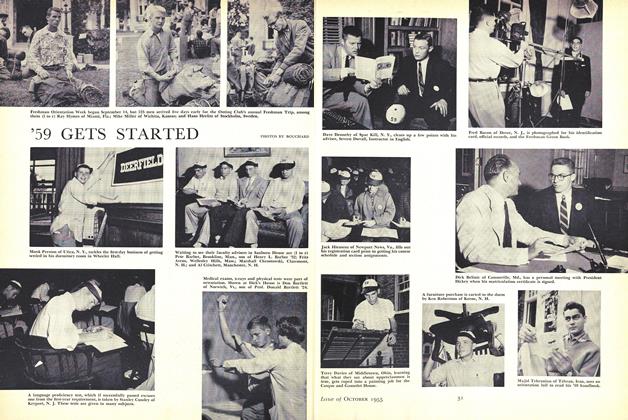

Feature'59 GETS STARTED

October 1955 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

October 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVFR, RICHARD P. WHITE -

Class Notes

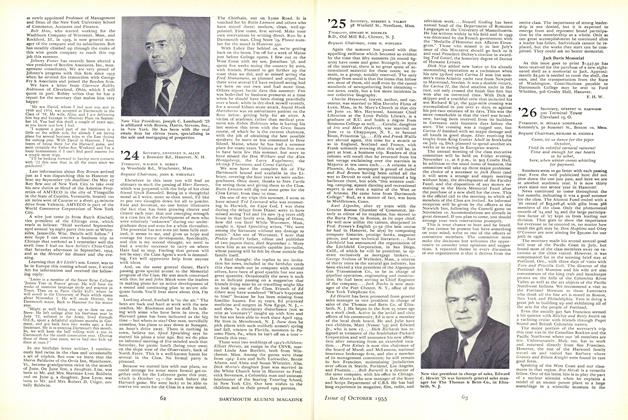

Class Notes1926

October 1955 By HERBERT H. HARWOOD, H. DONALD NORSTRAND, RICHARD M. NICHOLS

Books

-

Books

BooksBriefly Noted

JULY 1967 -

Books

BooksFrom the Ground Up

APRIL • 1985 By Courtney C. Brown '26 -

Books

BooksA SHORT HISTORY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE, VOL. 1: FOUNDATIONS OF AMERICAN LITERATURE,

January 1952 By H. G. R. -

Books

BooksWILD TRAIN: The Story of the Andrews Raiders

January 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksTHE BULLS AND THE BEARS: HOW THE STOCK EXCHANGE WORKS.

DECEMBER 1967 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

BooksBull Market

September 1975 By JOHN HURD '21