For opinions which appear in these columns the Editors alone are responsible

ADDING STRENGTH TO PERMANENCE

WHEN, within a few days, the Alumni Fund campaign for 1932 is officially inaugurated with the opening mailing piece to all of the alumni, the Fund committee and the class agents will be facing the most unusual and in many respects the most uncertain circumstances that the Fund has ever met. The quota will be the same as the quota of the past two years, $135,000. The amount of financial support requisite for fully sustaining the College in fulfilling its academic destiny will be greater than before, because of inevitable shrinkage in income from investments. The body of alumni will be enlarged with the addition of another large class of recent graduates. On the other hand, some of the most regular and most generous contributors to the Fund will be forced to reduce their gifts. A considerable number of others will be, in all sincerity and good faith, victims of the "psychological depression," and will want to reduce their gifts even though they have had no decrease in income and have had real increase in buying power, simply because retrenchment is the universal tendency of the times. And the rank and file of those who have not yet got the Fund habit will greet their class agents with the ready excuse "Depression!" on the tips of their tongues. It will be, indeed, a lively season for the class agents.

The class agents have already been active for several weeks, going over their class lists, trying to get in touch with that group of approximately 10 per cent who contribute 50 per cent of the amount subscribed in all such funds, urging the men whose resources have remained fairly constant to make up for their classmates who are in severe circumstances. As the campaign progresses towards its conclusion June 30, a stronger effort than ever before will be made to bring non-contributors into participation in the Fund. Regardless of the individual amounts contributed, a fine percentage of contributors this year would be a source of great gratification to all those who have the interests of the College close to heart.

One of the strongest appeals that the colleges will have for their alumni this year is their permanence and steadfastness in times of great disturbance. With the possible exception of the church, the college is the most lasting institution founded by man, surviving war, panic, change of government, social revolution and depression. The college has a sort of immortality peculiar to itself, joining the cumulative heritage of the strength and richness of age and tradition with a perennial renewal of youth. During a time when most of the institutions of the world have been shaken to their foundations and many are crumbling, alumni will find pleasure and satisfaction in turning to the college and, by individual participation in its steadfastly enduring life, lend it added strength when strength is most vital.

RELIGIO PUERI

SOME time ago in this MAGAZINE reference was made by one of the Christian workers in the College to the attitude of the undergraduates, as he had found it, toward religion, and its bearing on an allegation, which had been given rather irreverent expression in a DailyDartmouth editorial of the year before, that for religion the modern undergraduate "did not care a damn."

Without falling into what is probably the intended trap of condemning such an expression concerning such a subject, save only on the ground that it lacks something of gentlemanly good taste, we may say that in all probability the attitude taken by the editorial is not novel, save only in the startling form in which it is put. Undergraduates for a very long time have been prone to make light of religion. It seems to be the regular thing at that stage of the development of the human male perhaps one may, in these emancipated days, include the female as well. That it is frequently outgrown as the human being grows older and less egocentric is certain. But it is equally certain that in the days of one's youth, when the evil days come not and when life seems reasonably long and supernatural speculations rather futile, there is a very large proportion of the youthful world which feels, or thinks it feels, toward religion that indifference which the Daily Dartmouth's editor put into such arresting form. From the admonition of the Preacher (Eccl. 12:1) it is a fair inference that a similar propensity was known to exist in a much earlier day. One is self-sufficient at that age. Religion, as one comprehends it then, is a sort of old-wives' tale for very young children and for credulous elders, who feel the need of it.

And yet there is a doubt that youth is as indifferent to religion, properly understood, as it thinks and protests it is. As we recall the statement of the investigator above referred to, it indicated a lively curiosity as to what the elders really meant by religion, even if there were no profession of a tendency to believe therein. In part the contemptuous rejections of youth appear to rest on a feeling that what they may have learned about religion in their earlier infancy was akin to the Santa Claus legend—which, in the literal guise such teaching commonly assumes, may not be far from true. That there is anything in it which may be substituted, when one puts away childish things and begins to sing bass, usually does not come to be seen until some time after graduation. All that one sees is the preposterous character of one's infantile concepts. The tendency is to look with pity upon the few who retain their faith in Santa Claus. The sophisticate rejects what in boyhood he accepted and makes no secret of it—youth being inclined to outspoken honesty. If the Dartmouth's editor was nothing else, he was honest and boldly stated a truth as it seemed to him about the attitude of his fellows.

Was it really true, or only in the seeming? Undergraduates usually have some things, not of the material world, in which they do believe, although it would surprise most of them to be told that their faith savored of the religious. Call it honor, if you will. Call it reverence for plain-speaking, hatred of tale-bearing, disdain of the sneak, respect for straight dealing. After all, what men usually mean by "religion" is the outward trappings rather than the vital essence. Because one no longer entertains respect for the idea that a self-respecting God can be hoodwinked and cajoled by formal protestations of fealty, which are belied by one's conduct in daily life, and because one no longer accepts the idea of a Deity capable of acting like a rather testy and unreasonable grandfather, it does not follow necessarily that all belief is dead. What the undergraduate "doesn't care a damn" for is the pious twaddle in which he conceives religion to be dressed as a matter of necessity. The God of his nursery days he cannot even pretend to believe in, and therefore he scraps the whole idea. It puzzles him to find elderly professors of science much less sure than he himself is that there is nothing at all in religion. But it should not puzzle him. It should rather inspire the idea that perhaps he doesn't yet know just what religion really means and may be confusing his terms.

Religion is notoriously at a crisis, always in a state of flux. The heterodoxy of today is the orthodoxy of tomorrow. One recalls that so saintly a Christian as Dr. Tucker was once tried for heresy. Yet somehow it survives, and it is probable that never in the history of mankind was there more dire need of the realities of religion than now, in this age of materialism and wavering national ethics. The undergraduate does give a damn for religion—else the future is without hope. It won't be what his grandsire regarded as religion. It won't be black magic. Incantations and formulas will play no part in it. But it will be religion for all that; and for it a man will go to the stake now, as he would in the days of Peter and Paul.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAn Undergraduate Looks at His College

April 1932 By Howland H. Sargeant '32 -

Article

Article"Wildcatter"—A Play in One Act

April 1932 By James W. Riley '32 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

April 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1928

April 1932 By Leroy C. Milliken -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

April 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Article

ArticleThe Value of Fraternities to the College

April 1932 By Robert Coltman '32

Lettter from the Editor

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

MARCH 1931 -

Lettter from the Editor

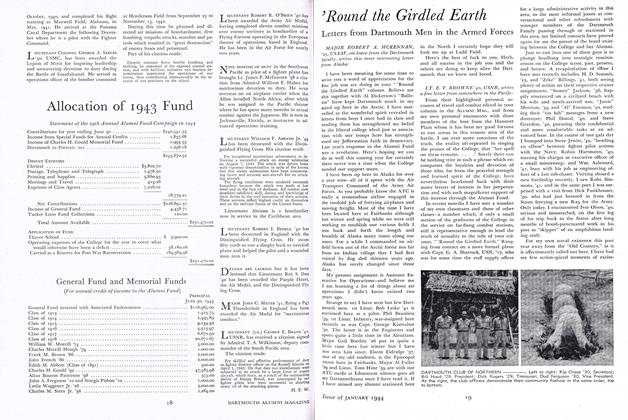

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

January 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorLetters from Dartmouth Men in the Armed Forces

February 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

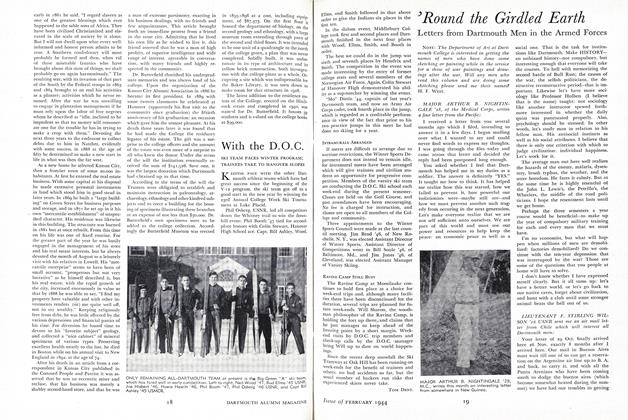

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1944 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorThe Real World

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Douglas Greenwood -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorTo an old friend

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Douglas Greenwood