NOT long ago a prominent alumnus of Brown University gave tongue to some rather vehement criticism of the custom of bestowing degrees honoriscausa, citing what he regarded as a flagrant case of the abuse to which many colleges are prone, although he named no names, merely stating that his own University had recently bestowed its accolade on "two men who in no way deserved and had in no sense earned" the degrees that were given them; adding that any Brown man would know whom he had in mind, and further implying that it would be well if the College gave more honorary degrees to its own sons and fewer to the sons of other colleges.

For the latter contention it is improbable that many sponsors could be convoked. There are evils enough about the honorary degree business, but in-breeding is not commonly one of them. In fact the readiness of the College to recognize conspicuous merit and to honor it, wherever found, is usually regarded as a redeeming feature. The real blemish is the persistent award, year after year, of degrees "in no way earned or deserved" but bestowed because of friendly consideration, pull, or other force, sometimes with the hope of financial response all too prominently in mind. What virtue there remains in honorary degrees is due to the readiness of any college to reward merit in eminent persons, regardless of their college affiliations, because of the fact that they have greatly distinguished themselves in some definite way.

There appears from the comment on the Brown criticism to be a shrewd suspicion that the offense was mainly toward the pet beliefs of the critic—that is, that degrees were bestowed on men holding social or political views that were anathema to him. Such things do happen, but are capable of defense on the ground that able and independent thinking merits recognition, even where the thinker reaches a conclusion to many minds unorthodox. A Fundamentalist might with some reason react against the giving of a degree to a scientist who had developed striking theories of evolution—might resent singling out a Charles Darwin as the recipient of a doctorate, while ready to approve an LL.D. for a Bryan—without proving very much beyond his own narrowness. Of course there is such a thing as paying too much reverence to thinking merely because it is "independent and courageous," virtuous as such thinking is, and too little reverence to its apparent good sense. It would take some courage and much independence to maintain the theory that the moon is made of green cheese in the face of hostile astronomers; but that would hardly justify making the holder of the notion an honorary Doctor of Science. Something depends on the possible validity of the thing thought, as well as on the courage required to think it. It is doubtful that any college is under any duty to bestow honorary degrees merely to demonstrate its readiness to be hospitable toward intellectual rebellion; but on the other hand it hardly can afford to demonstrate a dogged unwillingness to be hospitable, where the rebel has something in his favor. Independence is no sin—neither is it necessarily so resplendent a virtue that it must always expect applause.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEdward Tuck: A Biographical Sketch

June 1932 By Horatio S. Krans -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Greatest Benefactor

June 1932 By Russell R. Larmon -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

June 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Sports

SportsIron Man

June 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

June 1932 By Arthur E. McClary

Article

-

Article

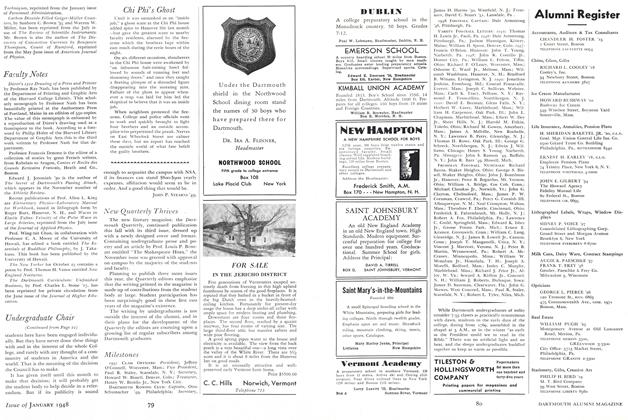

ArticleChi Phi's Ghost

January 1948 -

Article

ArticleAdvanced Placement

May 1960 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MAY 1984 -

Article

ArticleBuildings Spring Up and Athletes Get Down

MAY 1997 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleTHE LIFE AND LETTERS OF NATHAN SMITH, M.B., M.D.

November, 1914 By Emily A. Smith, C.C.S. -

Article

ArticleThe Fight

Sept/Oct 2000 By TOM SLEIGH