THE VALUE which has accrued to Dartmouth College through the life of Edward Tuck cannot be judged solely by a list of stocks or checks transmitted by him to its treasurer, important as these have been to an institution of which he is the largest benefactor. The timeliness of his gifts, the significance of their contribution in the period and in the entire span of life of the College, the manner in which they were offered and the interest which accompanied them, are all of vital importance. Then too, there is Edward Tuck, graduate of the College in the class of 1862, in whose life of usefulness and accumulated rare satisfactions and awards the College has shared. The parent is honored in the son.

In the 1890's, Dr. Tucker was devoting himself to the task of reconstructing the College. Those who are familiar with the problems of that period will recall the courage and self-sacrifice necessary for the acceptance and completion of the task. His keen vision dissipated the uncertainties of the future as he foresaw the opportunity of the College to take advantage of increased interest in higher education, and the responsibility on the institution to adjust its outlook, its method, its physical plant to meet these new conditions and opportunities. But even a leader of Dr. Tucker's rare ability could not do this unaided.

Midway in this process of change the support which he so vitally needed appeared from an unexpected source. Without solicitation, Edward Tuck, long removed from contact with the College personnel and activities, offered his gracious cooperation and support.

In a New York paper Mr. Tuck had found a statement that the trustees were urging Dr. Tucker to take a "leave of absence for rest and recuperation." He promptly wrote a letter to his old roommate, suggesting that Dr. Tucker should go to Europe and plan on a visit with Mr. and Mrs. Tuck. He gracefully removed any financial obstacles to such a trip and declared his desire to do something for Old Dartmouth." President Tucker accepted the invitation and on his arrival in Paris he was delighted to find that Mr. Tuck had the mtention'of establishing an endowment fund for amplifying the income devoted to the support of instruction.

Through a letter to the trustees Mr. Tuck declared that he wished to make a donation in memory of his father, Amos Tuck, graduate of Dartmouth in the class of 1835 and trustee from 1857 to 1866, and that he was delivering to them securities of a value of three hundred thousand dollars. In a short space of time, as Mr. Tuck foresaw, the value of these amounted to five hundred thousand dollars. In his letter announcing the gift one finds the expressed desire that the income should be used principally for maintaining or increasing the salaries of the President and faculty to such degree as might be necessary to retain or secure men of the "highest ability and culture," and for the establishment in the future of additional professorships in connection with the College proper or in post-graduate departments.

The letter continues: "I avail of this opportunity to say to you personally that my interest and pride in Old Dartmouth, in common I am sure with the same sentiments among all the graduates of the College, have been greatly stimulated and quickened in observing the large development which the College has taken and the high position it has assumed under your most intelligent, energetic and liberal management. My pleasure in giving to the College which was my father's Alma Mater as well as my own, and which he served as trustee, is doubly enhanced by the feeling that I can thus encourage and support in a material way the untiring and devoted labors of you, my intimate friend and my only roommate of college days, in bringing to the College a new period of prosperity and renown equal to any in its illustrious past."

Thus the two old friends, combining leadership, material means and moral support, joined in common effort for a worthy and significant purpose. The need for this partnership at that time becomes apparent when one considers the increasing strain put upon endowment plant and personnel by a constantly enlarging student body. The College enrollment was three hundred and fifteen in the academic year 1892-93, the first year of Dr. Tucker's term as President, and six hundred and twenty-seven in 1899-1900, the period in which the gift was made. The student body had nearly doubled in seven years. In the year 1908-09, the last year of Dr. Tucker's administration, the enrollment was eleven hundred and thirty-six.

"It was the most important individual factor in the reconstruction and expansion of the College" said Dr. Tucker. "The amount of his benefactions, and equally their object gave security to advances already made, and enabled the College in due time to take the initiative in a new field of academic training. They also gave direct moral support to the policy of the administration. Mr. Tuck was the first of the alumni of means to identify himself financially with what had begun to be known as the 'New Dartmouth'; and his aid preceded any organized or collective financial support on the part of the alumni. It was the more gratifying and assuring that it was altogether unsolicited, indeed unlooked for."

The income of this fund was of primary usefulness in raising the general level of faculty salaries. As a result of a plan proposed by Dr. Tucker and accepted by Mr. Tuck the income was also employed to establish advanced courses in the departments of Modern History, Economics, Political Science and Law, Sociology, and Modern Languages, these courses to constitute a graduate school which would prepare men for the world of affairs.

The reasons for this proposal may be of interest. Through an examination of statistics on past graduating classes Dr. Tucker had discovered that in the first 50 years of the life of the College, from 1771 to 1820, ninety per cent of the graduates entered the profess ions of law, ministry, teaching and medicine; that in the second span of 50 years, from 1821 to 1870, eighty- six per cent entered these professions; that in the thirty- year period from 1871 to 1900 the percentage had dropped to sixty-four per cent. (It may be of interest to know that in the following decade it decreased to fiftyone per cent.) As a result of such consideration of the shift in life work of the graduates of the College he came to the conclusion that the institution should recognize its obligations to offer some intervening training to bridge the gap between the liberal college and the world of affairs, even as this was done for those going into the recognized professions. He says, "It was a confession of the inutility or narrowness of a liberal education, for the colleges to leave their graduates in a helpless attitude before their new responsibilities, or to commit them altogether to the fortune of their personal initiative."

It is notable that the initiative for suggesting the establishment of a graduate school of business administration should have come from a spiritual and intellectual leader, and that it should have been heartily endorsed by one whose cultural interests and tastes are so apparent. The lives and thoughts of these two men indicate clearly that the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance, named for Edward Tuck's father, was not to subvert the objective of a liberal arts college but was to be allied to it. It was to be a bridge between the unharmonized cultural interests and the applied work of the graduate's field of activity, serving those entering the field of finance or transportation or manufacturing or distribution, as the Thayer School served the prospective engineers, and the Medical School the future doctors. The cultural values which a student acquires in the liberal college might perhaps tend to be too much confined to himself and too little contributed to his business activity or time unless he had knowledge of how to make his ideals or bents or sympathies effective. If business was to be raised to the dignity of a profession it seemed desirable to offer the essentials of preparation for professional life—an organized body of knowledge, some training in its skillful use, acceptance of obligation to one's fellows.

On such conceptions was the Amos Tuck School of Administration and Finance founded. It was the first graduate school of business in the United States, possibly the first one in the world. Its unique character caused much comment at the time. In editorials or articles of the period which are readily available for examination one finds the school praised for the opportunity it offered, not available elsewhere, for securing trained capacity for dealing with the problems of its field, for its assumption that a liberal education is essential before acquiring training in business methods, for its aid in securing acceptance for the idea "that education has any place in business life or that a business man should be as highly educated as any."

Having heartily accepted the plan proposed for the use of the income from the fund of five hundred thousand dollars, Mr. Tuck wished to complete the project which he had started by housing some of the departments affected by his original gift. Therefore, in 1901, he placed one hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars at the disposal of the Trustees for the erection of a building to provide facilities for the activities of the school, and to provide classrooms for the undergraduate departments of Economics, Political Science, and History.

The next major gift of Mr. Tuck strongly suggested what later became obvious—that he might be interested from time to time in one of the parts that make up the whole College, but that his major interest was the College whole and not a part, even though the latter bore the family name. One senses here the timeliness which always added to the importance of what he offered so freely, and which likewise was a tribute to his understanding of the heavy responsibilities of leadership in the Dartmouth situation. Dr. Nichols was beginning his career as President when Mr. Tuck added five hundred thousand dollars to the endowment fund which he had established, directing that the income be used for the increase of salaries of professors and instructors, with due regard for individual merit and distinction. Dr. Tucker wrote to him of the hearty reception accorded the announcement, and in reply Mr. Tuck expressed his pleasure that his gift to the College was causing so much happiness in Hanover. He said in part, "I have felt that the institution needed money very much and very soon if the brilliant opening of Dr. Nichols's career was to be maintained and the onward progress of the College inaugurated by you was to be carried along still further." Dartmouth must be one of the best educational institutions in the country. On that point Mr. Tuck has been insistent in word and act. Loyalty and a taste for the best, whether in colleges or vintages, are ingrained characteristics of this distinguished gentleman.

In his thoughtful action which followed three years later, one finds two of his major loyalties combined. Announcing to President Nichols the transfer to the College of stock valued at sixty-two thousand five hundred dollars, he said:

"Having long felt an affectionate interest in the French people as well as in Dartmouth College, I wish to promote among the students of the College a more intimate knowledge of the French language and of French thought and civilization. My desire is that our graduates, in so far as it may be given them to influence public opinion concerning the French nation, may, from their fuller understanding and appreciation of French culture and ideals, assist to bring about an even closer friendship between two peoples already united by many bonds of sympathy and of historic association, and separated only by difference of speech."

The income from this fund has been used in the support of means which aid the attainment of the ends he described.

A second gift made that year, 1913, has been affected by undeveloped plans of, others, but, in the minds of many, affected advantageously' to the College. Mr. Tuck gave forty-two thousand five hundred dollars "for the survey and building of the new road that is to connect the College center of the town, through the Hitchcock property, with the site of the contemplated new bridge." The road, soon known as Tuck Drive, was completed, but plans for the new bridge gather dust. At that time travelers to Hanover arrived by train at Norwich, Vermont, and it was hoped that a modern bridge and a handsome drive would introduce visitors and residents to the College Green. But mode of travel to Hanover has changed for the great majority, the motor car bringing the arrivals by way of the New Hampshire highways. Many of us, however, would consider the change fortunate and would have regret if the original plan had been carried out completely. For here is an old covered bridge, redolent of its use and of its history; and winding up to the campus is a curving road of beauty, lined with tall pines and overhanging green banks, a quiet haven for walks and idle dreaming. Its upper stretches move straight to the great library, and lead from the rooms of study back to the pines and the river.

Then, in 1917, came the war. The College experienced strain on its organization and structure far beyond the stress of its continued expansion and forward pace of the previous thirty years. The college organization had been set up for a normal year, but undergraduates were leaving in masses for enlistment in the various branches of the service. Income from tuition and room rents melted away, and many of the fixed expenses of the College remained almost constant. Inability to support the faculty corps would have resulted in serious losses in morale and personnel, irreparable for years. Drastic retrenchment might have affected the College permanently.

Quite unsolicited, and exacting the promise that no publicity should be given to his action, Mr. Tuck assumed obligation for sharing the responsibility of President and trustees. In June, 1917, when the problem first became acute, he transferred stocks having a value of one hundred and eighty thousand dollars to the Tuck Endowment Fund. In April, 1918, the Fund was increased by the addition of securities to take care of the unexpected depreciation of some securities already held. At this point the trustee record of thanks emphasizes the timeliness of the gift in this difficult situation of the College. In March, 1919, bank stock to the value of two hundred and twenty thousand dollars was presented to swell the total of the Endowment Fund. In accepting this addition to the sum of his benefactions the trustees declared, "Voted, in accepting this new gift on the conditions connected with it, that the trustees express to Mr. Edward Tuck their full appreciation of the significance, not only of his generous gifts, but of his intelligent thought and foresight in behalf of the College, through which in so large measure the prestige of Dartmouth College at the present day has been established."

Edward Tuck continued to care for his own. In December, 1919, he gave a block of securities valued at one hundred thousand dollars, a part of it to be used for the reconstruction of Tuck Hall. Owing to very rapid appreciation in the value of the stock, sixty thousand dollars was credited to the Tuck Endowment Fund and nearly sixty thousand dollars was used for reconstruction. This portion of the gift provided classroom space, as well as offices for instructors, thus relieving the pressure for such additional equipment. In June, 1921, he sent a check for ten thousand dollars after learning that there might be a deficit at the end of the College year.

The importance of these gifts in the period from 1917 to 1921 became even more apparent when the College after the close of the war was tested by the strain of expansion in numbers. The fact that the College could accept but a fraction of the large number of applicants resulted in more rigid examination and greater expectation on the part of the public and the men accepted. Faculty salaries had been increased to a point where the College could attempt to compensate its personnel adequately for their demonstrated loyalty and capacity, and it was enabled to make necessary and valued additions to the corps. Through its benefactor's thoughtfulness the College had consolidated advances made over a long period of years, and it was prepared to conserve the advantages of the extraordinary prestige which it now experienced.

His watchful oversight of college needs and his unfailing generosity continues through the remaining years, always accompanied by the gracious interest of Mrs. Tuck. In 1923 he transferred to the Tuck Fund account securities of a value of two hundred thousand dollars. In 1926 he exchanged some securities held by the College for some of his own, with obvious advantage to Dartmouth. At regular intervals through the following years appeared checks for ten thousand dollars, with accompanying notes suggesting that the President might find the checks useful in preventing deficits.

In 1925 he matured a plan which he had discussed with his old friend Mr. Kimball, long-time trustee of the College, and more recently with his respected associate in Dartmouth affairs, Mr. Thayer. To the latter he wrote, "The present residence is certainly out of date, and has neither the comfort nor the dignity appropriate for the home of a President of the College and especially of Mr. Hopkins. ..." Consequently the President received a letter saying that the writer was contributing some funds (which finally amounted to one hundred and thirty-three thousand dollars) "for the building of a new and appropriate residence for the President, worthy of the College with the high standing and reputation which it has now attained throughout the country, in such location as the trustees may decide upon."

"The inadequacy of the present home, which was President Tucker's and is now yours, was often a subject of discussion between Mr. Kimball and myself, and I am sure that it would be a great satisfaction to Tiim were he still living to know that the project we had talked about was now to be carried out. To myself it is a double satisfaction to feel that the planning and construction of the building are likely to be made with your personal approval and supervision, and it is my earnest hope that the house when completed will be occupied by yourself and your family for many years to come."

The house was built, and its usefulness to the President and the College has been apparent. Suitable for the entertainment of guests of the College, for the discharge of social responsibilities which President and Mrs. Hopkins assume, as well as for its use as the comfortable home they deserve, it has fulfilled the hopes of the donor. The latter in his typical unwillingness to define details of administration of his gifts refused to suggest the site or form of structure, contenting himself with the insistence that it should not bear his name. "There would be neither rime nor reason in attaching my name to it in any way. Don't consider it for a moment." He experienced the pleasure of learning that in the following year many institutions were contemplating the erection of a President's house, after seeing the value of his gift to Dartmouth.

It was in 1928 that he learned that the trustees, in considering the long-time plan for the physical development of the College, were considering the advisability of providing space for a Tuck School group in the area near Tuck Drive, on the plateau overlooking the river, removed from immediate proximity to the campus. Inquiring in regard to the expediency of the shift in location and the development of a separate group of buildings, he came to the conclusion that it was desirable to arrange this at once. He informed the trustees of his opinion and assured them that he was ready to take care of the cost. This amounted to more than seven hundred thousand dollars, absorbed by the receipt of securities worth six hundred thousand dollars and by credit for the value of the vacated building turned over to general college purposes.

Thus provision was made for the present Tuck School group, with its central administration building, named after the donor, containing classrooms, offices, and library; its two dormitories, Woodbury House and Chase House; and its handsome refectory, Stell Hall, named for Mrs. Tuck. Excellent in its conception and planning, beautiful in its location and architecture, it constitutes a handsome gift and valued addition.

Edward Tuck has retained his interest in the school since its inception, refusing to interfere in its administration, happy to hear of its contributions to its men and its field. Confidence in its Dean, Mr. Gray, and contact with him, knowledge of the respect in which the School and faculty are held generally, have given Mr. Tuck added satisfaction and assurance of its worth.

This long list of gifts of the last thirty years gives incomplete knowledge of the thoughtfulness of the benefactor, even when it is suggested that the total endowment in the Edward Tuck Endowment Fund, as listed in the report of the treasurer, amounts to three and a half million dollars and that the gifts to construction have reached a total of nearly a million dollars. The income received from the investments of the Edward Tuck Endowment Fund alone has amounted to over two million dollars since its establishment. In divers ways he has given much to which he would not allow publicity. There have' been gifts of miscellaneous character, testimony to his watchful concern. One recalls the presentation of the monument to the brave Richard Hall of the class of 1916, hero in service to France. Twice he has assumed the cost of collections of books. Owing to his concern, a silk Dartmouth flag hangs with those of its sister institutions in the library of the University of Louvain, and a room in the Maison des Nations Americaines of the Comite France-Amérique in Paris bears the name of the College.

But there are indirect gifts as well, and they are of impressive magnitude. In one way or another he has been of direct influence in securing gifts to Dartmouth totaling several million dollars. The influence that his gifts and his implicit faith have had in stimulating generosity in others and their confidence in Dartmouth cannot be estimated, but it is substantial. In addition to such indirect contribution, he made the invaluable one of nourishing the courage and faith of the board of trustees and the President at times when such qualities were demanded and were present but in need of substantiation and support.

It is interesting in connection with all his generous sharing of responsibility for the institution that this was assumed voluntarily as a result of his own desire and on his own initiative. Letters and visits of college officials, of Dr. Tucker and Mr. Kimball in past years, of President Hopkins in particular in recent years, have kept him informed of developments and plans. When he learned of need he was anxious to satisfy it, not perhaps because the College seemed poor and in need of aid but because he believed in it and its personnel, believed in its increasing power to influence its times. His Dartmouth connection as a graduate gave him his initial interest. His constant examination gave him conviction of essential values that must be preserved and given increased power. Edward Tuck is not one who associates himself with ineffective individuals, groups, or causes.

In satisfying his interest in the College, he secured much information about its changing activities and positive policies. There must have been frequent temptation for him to question policy or details of execution, for he was far from the situation, and many of the reasons for various announcements or changes must have been unavailable for consideration at the moment. Yet he was willing support to the group in control loyally, without interference.

President Hopkins' addresses at various times have been concerned with controversial social issues but they have not attracted criticism from Mr. Tuck. He has not assumed to direct what the College should do or what the President should believe or declare. He has been positive only in insisting that Dartmouth should be the best possible educational institution.

There are two exceptions to this policy of noninterference. He once smilingly but firmly prevented President Hopkins from flying to London from Paris, on the ground that he was too valuable cargo to be entrusted to the hazards of the air. Another time, on learning that the President and a trustee were acquiring pride in the speed of their cars, he facetiously suggested that some colleges had a rule that students could not have automobiles, and that it might be advisable to apply this to presidents and trustees as well.

Possibly this suggests the affectionate relationship existing between Mr. Tuck and President Hopkins. For the last fifteen years through extensive correspondence and personal contact their intimacy and profound mutual respect have developed. A survey of their letters and the personal statements they have freely expressed indicate obviously the joy and the value each has received through sharing thoughts and responsibilities and happy experiences with the other.

One form in which his generosity to Dartmouth has appeared has been highly prized by those individuals fortunate enough to have experienced it. Mr. Tuck has been a gracious, princely host at Vert-Mont or 82 Champs-Elysees or Monte Carlo to those members of the Dartmouth group who have had the privilege of being his guests. They are not likely to forget their association with that rare personality. His youthful spirit and twinkling eyes, his resolute opinions and strong loyalties, his discriminating taste, evidenced in manner, enjoyments, surroundings, leave an indelible impression. His profound loyalty to Dartmouth increases their own appreciation of its worth.

He represents in so many respects the aspirations of the College for its sons. If one of the primary functions of a liberal arts college is to educate men for usefulness Edward Tuck fulfills this requirement in superb degree. Institutions, groups, individuals without number, in this country and France are the beneficiaries of his generous and intelligent patronage. Through his thoughtfulness countless sick have been and will be made well, play and recreation have been afforded where they did not exist in like degree before, historical records and historical monuments have been preserved and displayed, art objects of rare interest and value donated to the public good, education supported in time of need. In recognition of his unique eminence in the cause of usefulness he has been honored by the highest awards within the power of the beneficiaries of his altruism: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor, Prix de Yertu, gold medal of the City of Paris, Century Medal of the Bank of France, medal of the National Museums of France. These are but a portion of the honors heaped on him by his beloved France.

Long ago the College suggested its high esteem by bestowing upon him the degree of Doctor of Laws. Two years and a half ago the trustees conferred the highest honor which their thoughts and desires could express. A golden bowl, in form the sole replica of the historic punch bowl presented to the first President of Dartmouth by the colonial governor of New Hampshire on the occasion of the first Commencement of the College, was given to Edward Tuck by them as individuals, to symbolize his unique position in the Dartmouth fellowship. The inscription follows:

EDWARD TUCK

Upon the records of the Trustees of Dartmouth College are spread formal resolutions significant of the gratitude of the official College for your many benefactions.

We, as individuals and alumni, having had as trustees the opportunity to realize best what the timeliness, the munificence and the wisdom of your gifts have contributed to the life of your and our Dartmouth, present to you this first and only replica of the historic President's Punch Bowl as a token of the gratitude and esteem which is ours and which no official action can express.

His life has been fused into the life of the College, affecting all those values it will transmit for uncounted years to come. His personality and works have acquired timelessness. In the quiet twilight at Vert-Mont he can review and foresee his boundless span of life, in deep satisfaction and clear joy.

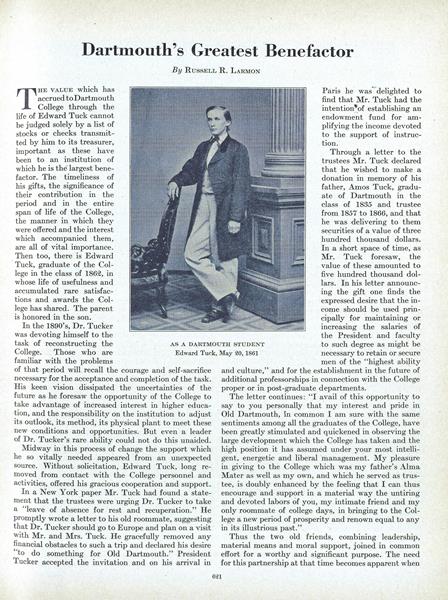

AS A DARTMOUTH STUDENT Edward Tuck, May 20, 1861

THE OLD TUCK SCHOOL Built in 1901 to house the newly created School. Renamed McNutt Hall when Mr. Tuck built the new home for the School in 1929

TUCK HALL AND WOODBURY HOUSE WITH TUCK DRIVE AND BAKER LIBRARY AT THE RIGHT

THE ENTRANCE TO CHASE HOUSE, TUCK SCHOOL

FOYER OF TUCK HALL SHOWING BUST OF EDWARD TUCK

CERCLE FRANgAIS ROOM Equipped in Robinson Hall by Mr. Tuck for a "fuller understanding and appreciation of French culture and ideals"

THE TUCK SCHOOL GROUP STELL HALL CHASE HOUSE TUCK HALL WOODBURY HOUSE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEdward Tuck: A Biographical Sketch

June 1932 By Horatio S. Krans -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1910

June 1932 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1926

June 1932 By J. Branton Wallace -

Sports

SportsIron Man

June 1932 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1905

June 1932 By Arthur E. McClary -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Meet

June 1932