Chairman, Department of Art

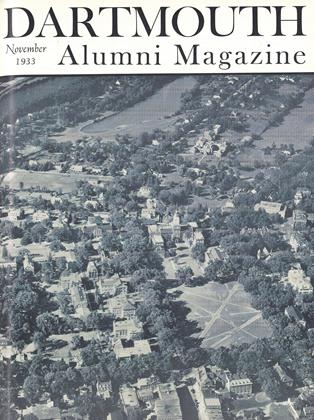

IN JUNE, 1932, Jose Clemente Orozco was commissioned by Dartmouth College to execute a large composition in fresco on the walls of the Reserve Book Room in the Baker Memorial Library. This project grew out of the desire of the Department of Art to have some good examples of mural painting for teaching purposes and of the need for a suitable decorative scheme for the Reserve Book Room in the library which is the long corridor in the basement running the full length of the building and corresponding in plan to that of the Main Delivery Hall on the first floor.

When the library was constructed no specific decorative features had been decided upon for this room. Assigned to the Reserve Book Department, where most of the books containing the prescribed readings for the various courses are issued on short two hour loans, it has developed into one of the most active rooms in the new library and the question of what sort of decoration might be added to its bare walls to give it a dignity consistent with its use had been a matter of increasing concern for several years.

Meantime the department of art, with the natural growth of its activities consequent upon the erection of the new art building, had been devoting its attention more and more to the problem of cultivating an intelligent interest in contemporary art and had become strongly persuaded of the educational advantage to be derived from having good examples of the work of some of the foremost painters of our time as teaching material on the walls of Carpenter Hall, particularly mural paintings, the special qualities of which cannot be understood through the medium of small reproductions.

In the spring of 1932 the department of art was able to secure the services of Senor Orozco to execute a small mural, the so-called "Release" panel in the corridor which connects Carpenter Hall with Baker Library, as a demonstration of the technique of true-fresco painting. It was during the period while the artist was thus engaged that he was invited to suggest a mural program for the Reserve Book Room. He proposed an "Epic of Civilization on the American Continent", an interpretation of the fundamental cultural forces which have governed the development of life in the western hemisphere from prehistoric times to the present day. Both the librarian and the college architect were quick to recognize in his plan a satisfactory solution of the decorative problem; the department of art gave its enthusiastic endorsement; and, after consideration, President Hopkins secured the approval of the Board of Trustees to the undertaking on the grounds of its immediate value as an educational enterprise.

Senor Orozco was duly commissioned to execute his mural project. For the purpose of emphasizing the educational aspect of the undertaking, he was given the title of visiting professor of art and, although he graciously consented to be available at times for private consultation with students, his real job—like that of all true artists—was to teach by doing. His lecture hall was the Reserve Book Room; his instruction in art, strictly extra-curricular, was his silent work upon the walls; and his classes were open to the hundreds of students who must pass daily to and from the more exigent duties connected with the prescribed reading for their regular courses.

The results cannot be measured in terms of examinations and credits but the earnest discussions of all manner of questions pertaining to the principles of art and the suitability of this or that kind of subject matter for mural decoration which this project has inspired among many who would otherwise have given scant attention to such interests are considered to be an important and proper contribution to the educational process. Further than that the College may be said to be contributing something equally valuable to society in providing an opportunity for one of the outstanding artists of our time to do the best work of which he is capable without any official restrictions as to the character of his expression; in other words, in extending the principle of academic freedom to one of the most important forms of public art.

Except for the services of a plasterer and such minor mechanical assistance as he has occasionally needed, the work has all been done by the artist alone, a truly Herculean task. When completed it will have been in progress for about two years, approximately half of the time being devoted to the actual painting.

The Artist

JOSE CLEMENTE OROZCO was born in 1883 in the state of Jalisco, Mexico, of parents descended trom early Spanish settlers. Having graduated from the National Agricultural School of Mexico in 1900, he spent four years at the National University, where he specialized in mathematics at the same time studying architectural drawing in the School of Fine Arts. For a time he was associated professionally with the architect Carlos Herrera and it was not until 1909 that he definitely decided on a career as an artist. From that year until the present he has occupied himself continuously with painting and, as one of the leaders of the "Syndicate of Painters and Sculptors" whose murals, executed under the patronage of the Ministry of Education, first drew the attention of the world at large to the significance of contemporary art in Mexico, Orozco was soon recognized as one of the most original and powerful members of the group.

Since coming to the United States in 1927 his work in all mediums has been widely sought by museums and collectors and critical estimates of his genius have appeared in most of the leading art journals of the world. Fresco is Orozco's favorite medium. Some competent critics have not hesitated to hail him as "the greatest fresco-painter since the Renaissance." In the "Epic of American Civilization" at Dartmouth, certainly one of the most important compositions he has ever undertaken, one may reasonably expect to find most of the qualities upon which his ultimate reputation will be founded. In short the College may well be congratulated in having in this fresco a first-rate example of the work of an artist for whom a notable place in the history of modern art is already secure.

The Paintings

The theme is civilization on the American Continent from prehistoric times to the present day. The work is in no sense an historical description of events or people; it is an epic interpretation in plastic symbols, the language of art, of the forces, constructive and destructive, which have created the patterns of human life in the Western Hemisphere. The compositions in the West Wing portray the rise and fall of the native Indian cultures before the arrival of the Europeans; those in the East Wing are concerned with American civilization since Columbus; and the central section, opposite the delivery desk, will deal chiefly with New England and Dartmouth College. These physically separate groups are bound together like the different movements of a symphony by a closely related development of major and minor themes—themes of idea as well as of color and form

Numbers have been assigned to the various sections of the walls, as indicated on the accompanying charts, to facilitate the identification of the parts described herewith:

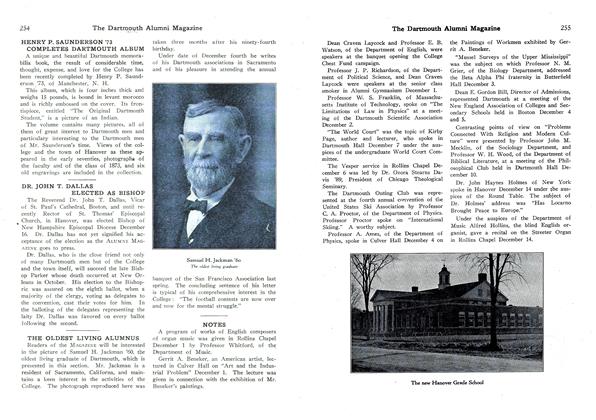

No. 1 (to the left of the West entrance) "Migrations"

The origin of American Civilization; representing the characteristic reactions of human kind to the impulse of change and progress; there are those who stand and wait; those who move with the crowd; the aggressive minority who lead; and those who fall by the wayside. The Utopian ideal of a "Promised Land" is said to be found in the traditions of most of the nomad groups which successively migrated from the north into the valley of Mexico and set up their several cultures.

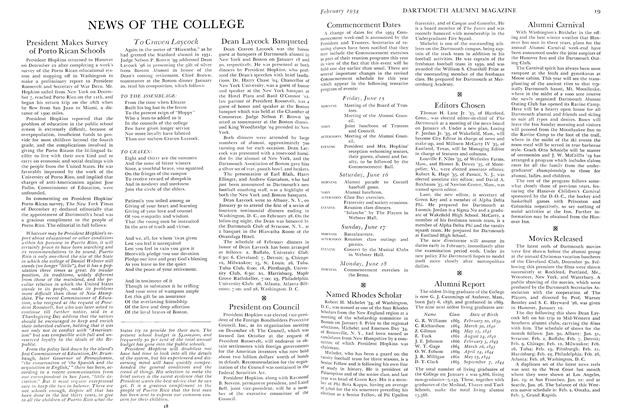

No. 2 (to the right of the West entrance) "Human Sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli"

The ideals which gave purpose and energy to the group consciousness in the nomadic stage, crystallize into institutions which demand some form of honorable human sacrifice to keep them alive. Specifically this panel depicts the propitiatory sacrifice to the Idol Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec God of War.

Nos. 3-9 "Quetzalcoatl" (Long west panel)

(The Long Wall of the West Wing depicts the rise and fall of the great civilization of the Mayas and the Toltecs, embracing a period of several thousand years, and including the highest cultural achievements of the native Indian races. The story is told in terms of the Myth of Quetzalcoatl which is bracketed between a symbol on the left of the Militaristic Aztecs, who conquered the Toltecs, and a visionary symbol on the right of the Spanish Conquest which overcame the Aztecs.)

The worship of Quetzalcoatl ("The Plumed Serpent") has its counterpart in the man-god concepts of many of the primitive religions of the world and includes some of the characteristics of pantheistic systems such as those of ancient Greece and Scandinavia; some elements of systems based on sun-worship such as we find in Egypt and the Orient; and some striking resemblances to the more advanced prophet-messiah formula associated with the idea of an Omnipotent Creator exemplified in Buddhism, Christianity, and Mahometanism. The concept of a supreme deity with the same attributes as the Quetzalcoatl of the Toltecs, Mayas, and Aztecs is found under different names among all the aboriginal tribes of North and South America (the beneficent Great Spirit, Manitou, for example of our Western Indians, and the Manibozho of the Algonquins from whom Longfellow derived his figure of Hiawatha). It is a curious fact that these names were applied locally to the white man wherever he first appeared among the Indians. All the arts of life that conduce to the welfare of mankind are as- sociated in one combination or another with this god-hero who is represented as teaching his people the various crafts and the ethical codes upon which a satisfactory life among men is founded.

No. 3 "Aztec Warriors"

This carries on the aggressive theme of the Migration (No. 1) and corresponds plastically to the symbol of the European conquest at the other end of the wall (No. 9). The knights of the eagle and the knights of the tiger can be distinguished by their uniforms, carrying banners made of silver and feathers. The sculptured head of the plumed-serpent, symbol of Quetzalcoatl, refers to the native cultural heritage.

No. 4 "Teotihuacan—The Gods"

No. 5 "House and Volcano of Orizaba"

Rising up between two pyramids (typical of the temples devoted to his worship) appears the Great White Father, the King of the Gods and the Ruler and Teacher of men. Behind and on either side appear the figures of the older gods who symbolize the forces which influence the destinies of men. From left to right they are specifically the God of Greed, dressed in the skins of his victims; the God of Magic, with feet of smoking mirrors; the God of Rain and Storm; the God of Death; the God of War, with feet of feathers;-and the God of Fire, whose home was in the cone of the volcano Orizaba.

Quetzalcoatl is represented as arousing men from their intellectual and spiritual torpor to learn the arts of civilization. To the right of the sleeping figures is a group of people (No. 5) conversing together on the porch of a Toltec house, a symbol of the beginnings of co-operation and understanding without which no society can exist.

No. 6 "Agriculturist, Sculptor, and Astronomer"

The three large figures symbolize the outstanding accomplishments in Agriculture, Art, and Science. The ancient American Civilization was founded on an agricultural economy growing out of the expert cultivation and use of maize; the monumental carvings of the Toltecs and Mayas are among the most remarkable sculptures that the world has produced; and the understanding of the heavens which these peoples possessed was actually in advance of that of Western Europe at the same period.

No. 7 "The Reactionaries"

According to legend Quetzalcoatl's departure from the land of the Toltecs was brought about by the machinations of evil priests and magicians who sought by a series of treacheries and enchantments to counteract his beneficent influence and to regain control for the powers of darkness over the minds and hearts of men. Witchcraft and human sacrifice were re-established and in their wake followed war, disease, and the destruction of Tollan, the great Toltec city.

No. 8 "The Prophecy of Quetzalcoatl"

This part of the legend depicts the God as a disappointed messiah, who, renounced by his people, departs into the East from whence he came on a boat made of serpents, prophesying that he would return in five hundred years with other white gods who would destroy the civilization of those who failed to follow his precepts and set up a new civilization in its stead.

No. 9 "Europe"

A symbol of the European civilization of the time of the Spanish Conquest. The men and horses in armor, the Church Militant, and the classic and mediaeval elements in Spanish Renaissance culture are suggested.

No. 10 "The Missionaries—Dartmouth College"

Symbols of Dartmouth College.

No. 11-A "Missionaries and Explorers"

No. 11-B "Settlers"

The Puritans in New England.

No. 12-A} "19th Century Immigrants"No. 12-B}

Nos. 13 to 19 "The Return of Quetzalcoatl" (Eastlong panel) This series symbolizes the white man's civilization on the American continent, past, present, and future.

No. 13 "Cortez' Ships Destroyed by Himself' Symbol of the determination of the white man to colonize America.

No. 14 "Hernan Cortez" Symbolizing the conquest of the continent under the aegis of the Cross and the end of the old civilization.

No. 15 "The* Machine—lndustrial Development" Symbolizing the white man's development of the natural resources of the continent.

No. 16 "Anglo-America, Town Meeting and School Teacher"

An interpretation of the racial psychology and the social and political ideals of North America.

No. 17 "Hispano-America—The Rebel and His International Enemies" An interpretation of the racial psychology and the social and political ideals of Spanish-America.

Nos. 18 and 19 "The End of Superstition—Triumph of Freedom"

No. 20 "Modern Human Sacrifice" (East endpanels) A complement to panel No. a.

No. 21 "Nationalism, Armaments"

No. 22 and 23 Decorative panels.

Panel No. 1—"Migrations"

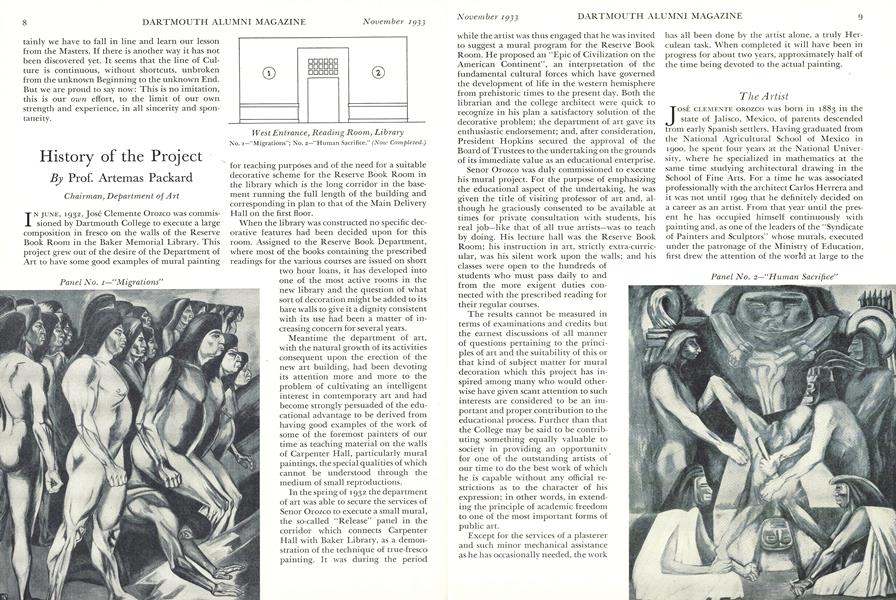

West Entrance, Reading Room, Library No. 1—"Migrations"; No. 2—"Human Sacrifice." (Now Completed.)

Panel No. 2—"Human Sacrifice"

Opposite Delivery Desk No. 10—"Dartmouth College"; No. 11-A—"Missionaries and Explorers"; No. 11-B—"Settlers"; Nos. 12-A and 12-B—"l9th Century Immigrants." (Thesepanels not yet started.)

East End Panels No. 20—"Modern Human Sacrifice"; No. 21—"Nationalism, Armaments"; Nos. 22 and 23—Decorative panels. (Work on this wall not yet started.)

Panel No. 9—"Europe" A symbol of the European civilization at the time of the Spanish Conquest.

Long East Panel, Reserve Book Room No. 13—"Cortez' ships destroyed by himself"; No. 14—"Hernan Cortez"; No. 15—"The Machine—lndustrial Development"; No. 16"Anglo-America, Town Meeting and School Teacher"; No. 17—"Hispano-America—The Rebel and His International Enemies"; Nos. 18 and 19—"The End of Superstition—Triumph of Freedom/' (The artist has completed panels Nos. 75,14, and 15. He is now paintingthe others in this section.)

Panels 13 and 14—'Hernan Cortex"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

November 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

November 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

November 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

November 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

November 1933 By Laurence W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1903

November 1933 By Dr. Edward K. Burbeck