Photographs remind us that timelessness and tradition are valued, that change is profoundly disorienting. And so we go on making pictures of ourselves.

THIRTY-TWO THOUSAND YEARS AGO, in a cave in Chauvet, in the south of France, an ancient relative of ours filled his mouth with a mixture of milk and soot and pulverized rock. He pressed his hand against the wall of the cave, squeezed his lips together, and sprayed the messy, chalky mixture at it. When he pulled his hand away from the rock, there was its image, in negative silhouette. He stood back and, for reasons totally mysterious yet altogether understandable, admired the mark on the wall. "I was here," the handprint on the rock declared. "This was me."

Every day in the United States 41,506,844 photographs are taken. Some are meant for public attention: to influence and to inform, to delight and to entertain, 3to seduce and to sell. They fill virtually every corner of our consciousness, our newspapers and magazines, our billboards and walls, and our ever-flickering screens. Together they create a culture's memory of itself. And they communicate in what, by now, amounts to a universal, parallel language. A language in which, from earliest childhood, we have learned to converse. A language of images. The existence of this visual language is so elementally simple as to be the most taken-for-granted of modern phenomena. But consider: A photograph in this morning's paper represents one infinitesimal fraction of a second, torn from the continuum of time, removed from all connection with its original context, and presented for your attention. The instinctive, immediate, and involuntary response to create for that moment a past and a future. The photograph cannot itself make us hungry or injured or afraid. But it can trigger a sense memory of a moment in which we might have felt the same emotion we assume is part of the condition depicted. To look at the picture is, in some way, to imagine ourselves in the scene. To look at a photo of a moment passed is to transport ourselves back in time. The truths that lie within a photo are ones that we assemble from the raw material of our experiences. For the camera has created the reverse of Renaissance perspective. Instead of all Creation convening at a vanishing point representing infinity and implying God, the physical world now exists in reference to the eye of the beholder. The point at which the viewer stands becomes the fulcrum around which everything revolves. Physical reality is like a vast beacon—not one which radiates light outward, but one in which appearances travel in—entering through the eye and ultimately resting in the heart. The moment of the photo's making becomes part of a dual experience that involves the moment of its viewing. The always-present content of a photo is the difference between the two moments. Thus the apparently fixed content of a photo is fractured and multiplied into many meanings, one for each viewer and for each viewing

The overwhelming majority of the photographs made are, simply, pictures. They are destined not to carry the story of history, but simply to serve as tiles in the mosaic of an individual life. Their final destination is not the pages of our journals nor the walls of our museums. They are to be held somewhat closer to the heart. They are pictures of our loved ones and neighbors and friends. They are pictures of ourselves. They are records of our present made with the intention of showing, sometime in the future, what our past looked like. As we observe a photo, it is as if someone has laid a translucent paper over our thoughts and made a tracing of our memories.

A photo transports its subject from the then to the now; from the there to the here. A personal photo borrows a single moment from a life story and makes a gift of it to future viewers. The moment is also taken out of the realm of private experience—a single living memory—and thrust into the domain of public examination. The image becomes part of the history of how things looked then. It is the invention of photography that created the idea of nostalgia. Previously, the past consisted of a series of experiences, each superseded and cancelled out by the ones that followed. Now, photographs provide a concrete reminder of what no longer is. They put in our hands the evidence that the moments depicted—the moments lived—are forever lost.

Several months ago the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art presented an exhibition of photos taken by anonymous amateurs like the rest of us. The unique and surprising appeal of the photos—in the context of an art museum—was their unpremeditated beauty and mystery. On the walls of a museum, these bits of paper take on the character of folk art. The earnest, naive effort to simply record experience has the utility of a patchwork quilt, the quirkiness of a hand-carved weather vane. And they raise a fundamental question: Does something qualify as a work of art based on what the maker knew upon creating it, or based upon what the viewer learns upon seeing it? When we look at images that are guileless and unprepossessing, what we read into them is based on our own sense of irony or wit. We see in them the formal structure that derives from our own preconceptions about aesthetics. When we look at images like these, we sense that we are free of the pressure to understand the artist's intentions. Those intentions have been rendered transparent and comprehensible. Yet, though they are essentially utilitarian, they possess something lacking in mug shots or geological survey photos. The maker of the picture invested the scene not only with intention, but with emotion. The viewer invests it not only with curiosity but with experience. Perhaps it is simply aesthetic boredom that compels us to regard these essentially personal artifacts as "art," but perhaps it is art's very purpose to prompt the viewer to explore his own responses to the things before his eyes. If, as someone once observed, art is a dream that the artist and the viewer are having simultaneously, to see a snapshot might be to confront a memory that exists in someone else's thoughts.

Look at the photos in this magazine. The families, the friends, the fellow students, the buildings, and the trees represented are gone—physically gone in many cases, but at the very least replaced by ones transformed by new knowledge, new experiences. To dream of preserving something in a world ever on the move is, we know, futile. But in a world of rapid change and inevitable loss, we can't help but feel that there are some things that time has no right to destroy. Perhaps our identification with our images has its roots in our spiritual beliefs, in the conviction that life is more than a series of physical impulses that cease to have any meaning the instant they stop. A person photographed has achieved a moment of redemption. The moment captured has been saved from the fate of being forever forgotten. As the age of machines has been superseded by the age of electronics, and as the cyber age redefines the elemental concept of both time and space, we fear that change occurs too fast for us to observe and absorb. We seem unable to apprehend time for long enough to create an appropriate body of memory. Our snapshots, our mementos, our images now become more dear to us than ever. They remind us that, for most of history, timelessness and tradition were valued, and change was seen as a profoundly disorienting phenomenon. And so we will doubtless go on making pictures of ourselves. We will etch our faces onto pieces of paper (and, since they're the reverse of the image we see in the mirror, we'll complain that they don't look like us). We will never escape an instinctive longing for how things were, or how we wished them to be, at the moment they were frozen by the camera. In a world of limiTLess data and ceaseless noise, these scraps of paper are our last best chance to say: "I was here. This was me."

Editorial design consultant TOM BENTKOWSKI is the former design director of Liie,for whichhe wrote the column "Speaking of Pictures."

PHOTOGRAPHS create a culture's memory of itself.

As we observe a photo,it is as if someone has laid a transluent paper over our thoughts and made a tracing of our memories.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

June 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Article

ArticleHow to Read a Photograph

June 1999 By Andy Grundberg -

Article

ArticleWorking with the Great Ones

June 1999 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Article

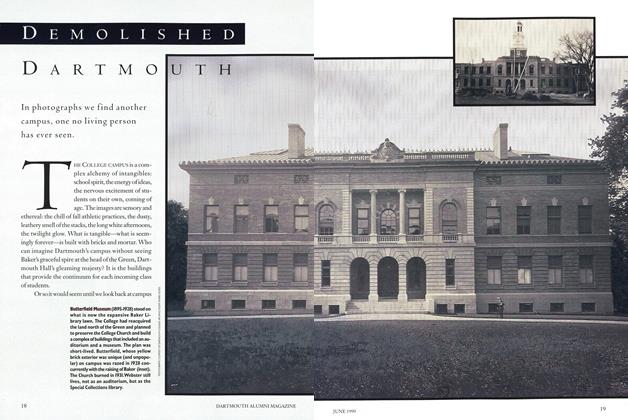

ArticleDemolished Dartmouth

June 1999 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

June 1999 By Jeffrey D. Boylan, R. James "Wazoo" Wasz -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

June 1999 By Mark Soane, Rick Bercuvitz

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SECOND IN TRIANGULAR DEBATE

-

Article

ArticleTOTALLY TUBULAR

Mar/Apr 2008 -

Article

ArticleA Challenge Still Unanswered

April 1947 By BUDD SCHULBERG '36 -

Article

ArticleSKIING

FEBRUARY 1964 By DAVE ORR '57 -

Article

ArticleTHE FACULTY

FEBRUARY 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Article

ArticleNotes from Deutsehland's other Green Party

APRIL 1999 By Jane Varner '90