IT HAS BEEN my privilege to have a somewhat remarkable interview with Orozco, who, despite our disagreement in the interpretation of terms, I found to be one of the most delightful personalities in the contemporary art world. He is a short, but well set-up man, with a wealth of black hair, a small, close-cropped mustache, and eyes that seem to pop through thick, amber-rimmed glasses. With him at Dartmouth, where he holds the title of Visiting Professor of Fine Arts during the execution of his murals, is his wife and three youngsters. When not at work on the huge panels, Orozco dresses in a plain and inexpensive sack suit, and his tie is straggling. In intense conversation he gesticulates with his right arm, and handless left one, in the picturesque manner of the Latin. He is soft spoken, almost mild. While one may question somewhat the logic of his reasoning which disassociates the responsibility of the clear-cut "story" which a viewer reads into a picture from the aesthetic intent, there can be no questioning of his sincerity.

I had already studied the now more than half completed frescoes in Baker Library, and had inquired their purpose. It is a personal conviction that the "story" of a work of art does matter, and during the life-time of its active influence is of greater importance than its aesthetic significance.

Compared with his Mexican murals, where the "idea" was dominant, the frescoes at Dartmouth are, at this writing, tamely historical—although they have been otherwise interpreted. In some ways they are best compared with Abbey's famous and much vilified "Holy Grail" series in the Boston Public Library. Technically they are far apart, and Abbey strove for pleasant decoration, while Orozco seeks forceful plasticity. But each tells a story in chronological fashion, chapter by chapter.

For me, Orozco's every brush stroke is born of deep-rooted conviction, even though the course of our discussion would seem to indicate that he feels interpretation as being the responsibility of the viewer. I think his works in Mexico are potent messages to the living in whose time they were created. I think he believed sincerely in the corruption of native politics, baneful outside interference by militaristic and capitalistic interests, and in the existence of a rapacious and thieving clergy. His convictions may have been those of a hot-heated young revolutionist. His convictions may have been arrived at by an earnest effort at impartial consideration. They may have been totally justified by facts. They may not have been justified at all. Yet there seems no reason to doubt Orozco's integrity.

Art Editor, Boston Transcript

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

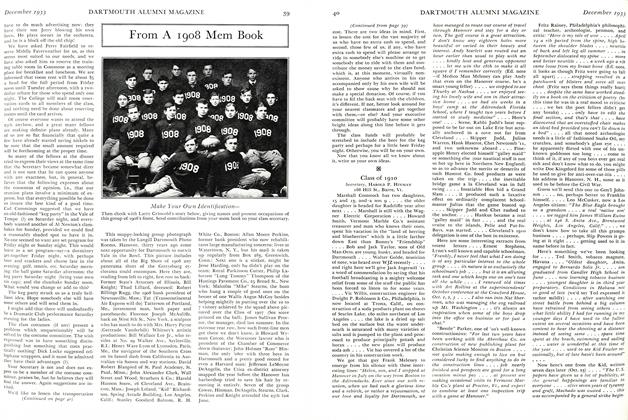

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING, A WAY OF LIFE

December 1933 By Arthur G. Tozzer '02

Article

-

Article

ArticleMajors

December 1974 -

Article

ArticleThe President and PC

June 1993 -

Article

ArticleAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2004 By Katherine Taylor '97 -

Article

ArticlePractical Memorial

December 1945 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleValedictory to 1959

JULY 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Article

ArticleWith the D.O.C.

January 1956 By ROBERTS W. FRENCH '56