Another Convocation somehow seems in order at the present time, now that House Party has come and gone and the football season is almost over. For the majority of undergraduates have been making little more than a half-hearted pretence at attending classes and accomplishing work since October. A bewildering series of football week-ends, topped by Fall House Party, and succeeded ten days later by Thanksgiving recess has not proved particularly conducive to the scholastic life.

But now, with the beginning of the three week stretch to Christmas, the boys are "putting away childish things"—mighty swell things they were, too—and getting down to the pretty task of meeting that final deadline in February. And the odds are all in favor of no appreciable drop in the College's scholastic standings. We append that paradoxical statement merely in self-defence. We've been wrong on almost every other prediction this semester.

WHAT RAH-RAH SPIRIT?

For instance, this writer, along with Steeplejack and The Dartmouth to some extent, was firmly of the opinion that Dartmouth's imposing football schedule, the return of Freshman Rules and rallies, and the general atmosphere on the campus was probably slated to effect a change in the direction of rah-rah collegiatism on the part of the student body. No such change was effected. The Dartmouth student body reversing all past custom, refused to get excited.

Startled as we were by the sight of an apathetic campus suddenly transformed into an apathetic campus under the tomtom magic of football, we are yet puzzled by one question. In all the wisdom we have acquired through three and a half years at Dartmouth we can find no solution. Is there anything on the face of the earth or under it that can arouse the Dartmouth student body?

If the answer to this very rhetorical question is a quiet negative, an interestingcorollary must follow as a matter of course. What is Dartmouth apathy? And if the answer to this is a refusal to become excited over unimportant issues, then Dartmouth College is definitely on its way to leadership among American educational institutions. Perhaps the fact that "nothing ever happens at Dartmouth" is a tacit admission of true undergraduate maturity. Then again, it might mean something else. Indeed, there is much to be said on both sides of the question, to mint a new phrase.

WE'LL TRY DOCTOR

The sole truly unaccountable fact of the last two months is that Steeplejack, Dartmouth's self-styled "Journal of Controversy and Interpretation" maintained a circulation of better than eight hundred copies for each of its four issues to date. This newspaper-magazine-critique was founded on the theory (which it followed to a certain degree in practice) that the campus was interested or could be made interested in thought about the Campus and the Outside World. In other words, amid all the actual confusion induced by a bewildering social program, some twenty-five per cent of the student body bought and really read a journal of controversy calling for intelligent thought while spelling out its four pages.

Just what this may mean, we do not know. (In September we would have known, we can promise all readers.) At any event, it looks fairly reasonable to assume that there is a base upon which to build a clear-thinking community at Dartmouth, come what may. Two campus organizations "The Junto," official offspring of the common-law mating of The Arts and The Round Table, and "The Dartmouth Union," last relict of The Dartmouth Christian Association—apparently are working under some similar assumption. The first is dedicated to the proposition that student thinking about politics, economics and esthetics in connection with the outside world might be a good idea. The latter is striving to lower the barriers between student and faculty and also to stimulate intelligent discussion of religion and religious questions.

Both groups have something to say to the campus. Whether or not the campus will listen is another matter. We favor the former; voices have been heard crying in the Dartmouth wilderness not infrequently before, and have been taken in to sit beside the fire out of common charity, if nothing else.

THOU SHALT NOT

Twelve special patrolmen were assigned to assist Spud Bray, beloved policeman of the campus; fraternity house presidents grew gray hairs far beyond their years; and Hanover fountains sold less ginger ale than ever before at the same time, as Dartmouth's 1933 Fall House Party proceeded through its allotted three days. The Administration, apparently determined to quell national rumors about the wildness of Hanover social affairs, firmly informed the undergraduates, via the fraternities, that this party was going to be orderly and sober, or else In consequence, sober and orderly it was.

Granting that in the past the undergraduate has every so often overstepped the bounds of discretion, the curtailment of the old-style "wild" Dartmouth party is yet somewhat ironic, when one considers dispassionately what good boys Dartmouth men are at heart. It is only that so many of them want to be gentlemen-hellers and a little more interesting to themselves and the folks back home than the average men at Princeton, Yale or Harvard that they have unconsciously helped to perpetuate the innocently shady traditions about their college.

Nor will all the Administration pressure in the world, which obviously would never be invoked, check that perpetuation. Our children's children will still bustle home at vacation time to spread the glad gospel that Dartmouth is the last outpost of freedom and romance in the work-a-day world.

WIN, LOSE AND DRAW

The outcome of the Chicago game is as yet unknown as we go to press, but the 1933 football season will undoubtedly go down on the books as one of the strangest in Dartmouth gridiron history. To win but one major game, to tie another, and to drop three by the narrowest of margins, certainly seems a record for long discussion in the winter months. Coach Cannell's Bates-game prediction, that we would not win or lose games by any considerable scores, reveals itself as the very word of a masculine Cassandra.

The metaphor does not, we believe, hold in toto, for the Trojan oracle was considered "a prophet without honor in her own land." Mr. Cannell regained a good deal of his 1931 popularity on the campus with his accomplishments of this season. Faced with a dearth of sufficient good material—we say "dearth" in comparison with the material available to a football college like Notre Dame or Wisconsin—he made the best of what he had and proved fairly successful. The fault, if not winning the majority of the games merits that condemnation, lies neither with the coach or the team, which somehow failed to click on a few occasions. Though it is not our duty nor intention to act as official apologist for the football season, we do believe that both Yale and Cornell won on breaks which might just as easily have gone our way.

As we have noted above, the campus remained particularly sane on the whole subject. To be fair all around, this "rational acceptance" might be regarded as sheer hopelessness, but we refuse to consider it as such. Rather we think that Dartmouth has come to the point at which so many of its sister institutions now stand, that of being able to take its football or leave it alone. The campus is realizing that the members of the football squad attend the same classes that it does, and that they go to college too. Football as something apart from the life of the college no longer exists at Dartmouth.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1933 By Rees H. Bowen -

Class Notes

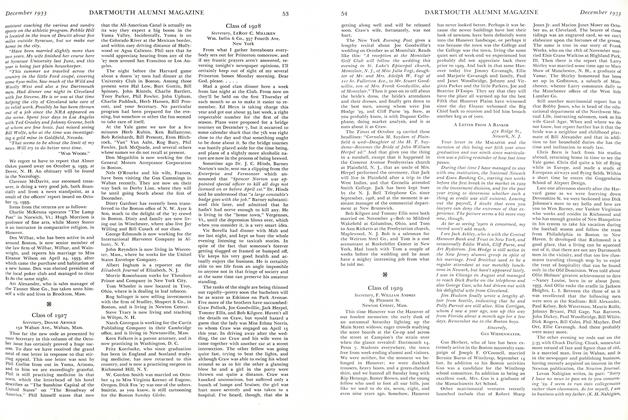

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

December 1933 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Sports

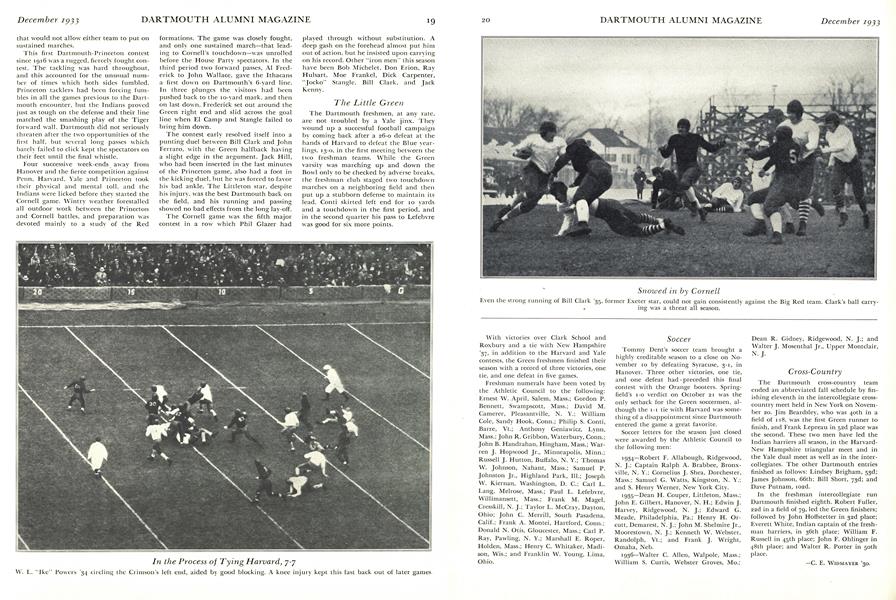

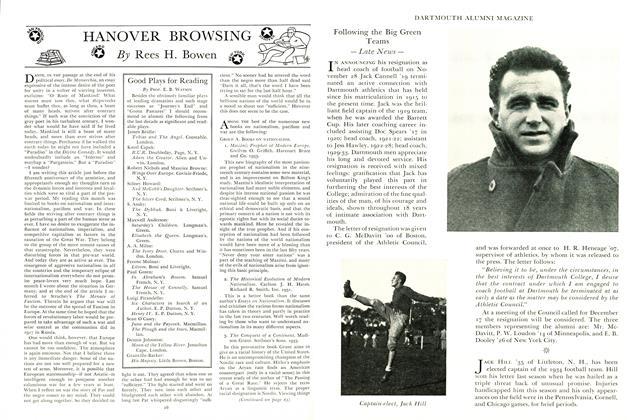

SportsFOLLOWING THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

December 1933 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

December 1933 By F. William Andres, Gus Wiedenmayer -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING, A WAY OF LIFE

December 1933 By Arthur G. Tozzer '02