His Life and Works by Herbert Faulkner West, Cranley & Day:London.

"Therefore will I have our Courtier a perfect horseman for everie saddle. And beside the skill in horses, and in whatsoever belongeth to a horseman, let him set all his delight and diligence to wade in everie thing a little farther than other men, so that he may be knowne among all men for one that is excellent." —Count Baldassare Castiglione: The Book of the Courtier. Done intoEnglish by Sir Thomas Hoby Anno,1561.

The days of scoops are not over. A Dartmouth professor with the help of the President and the Trustees shipped across the seas and has written the life of the most gallant of Scots, a man whose pulse has always beaten in adventurous rhythms.

The English are sensitively aware of the irony that an American, and, what is more, an American professor (Mr. Cunninghame Graham dislikes professors, but he tells Mr. West that he seems completely unlike any professor he has ever known) should have sailed out of the democratic United States and written the first biography of a gentleman so distinguished in Scotland and London.

Americans do not know Mr. Cunninghame Graham, even though he is the author of some thirty books, but Englishmen do, for in London they have seen him riding his horses still at the age of eighty with a youthful spirit making spectators breathe faster and with hair seemingly wild but blown by winds of romantic South American memories into gentle debonairness. Consequently they are buying and reading the book, which has not yet found an American publisher. Newpapers and magazines in England and Scotland are giving it from a one-column to a full-page review.

Cunninghame Graham is one of those rare persons who has had the urge and the opportunity throughout a career of robust vitality to live picturesquely and dangerously. His mother was Spanish, his father a Scottish laird of ancient lineage harking back to the illustrious and noble Earls of Stathearn, Menteith, and Airth descended from the Royal Family of Scotland.

He was born in London, dreamed his visions at Harrow, followed them to South America at 17, and spent 16 years there among horses and cattle men and Gauchos and supported himself by ranching. At 27 he married a Chilean woman, returned to his ancestral estates where he faced debts amounting to $500,000, tried as a gentleman farmer to make his estates pay and then had to sell them despite the fact that they had been in the family for 500 years.

Mr. Cunninghame Graham turned to politics, talked a vehement and sincere Socialism, and for six years shocked the propertied classes who knew that England was right because Victoria was virtuous. His words were not empty: he made them good on "Bloody Sunday" at the Battle of Trafalgar Square.

He quit politics. He wrote books. He enjoyed the friendship of Shaw, Hudson, Blunt, and Conrad. He travelled beaten and unbeaten paths. He struck up acquaintanceships often with failures by a romantic preference in the United States, Central America, South America, Spain, Madeira, the Canary Islands, and Morocco.

Professor West's problem was more difficult than appears on the surface. Even though he is a friend of Mr. Cunninghame Graham, he did not have access to his private papers. Mr. West is no Mr. Archibald Henderson and Cunninghame Graham no Bernard Shaw. The task of the biographer was no less than to write a life without having access to correspondence and to MSS. or even to dates, let alone intimate details of life in undress, except in so far as they appear in the thirty volumes.

The result is a tactful and enthusiastic interpretation without any attempt to probe or to weigh critically. And this is part of the charm of the book, which at the same time leaves one unsatisfied. Still Professor West's buoyancy is full of Vitamins A and D and for those who cannot be gentleman-adventurers here is a bottle with rejuvenating pellets, like a magical one always well stocked, to bring back colour into steam-heated cheeks and thermostated blood streams.

Mr. Cunninghame Graham has a titillating turn of phrase—and Professor West stands with his idol—when it comes to such questions as imperialism and respectability, the philosophy of failure, the white man's burden and whiskey, Conrad and the ironic attitude to life, naturally perverse Latins and metaphysical Northerners, Nietzsche and slave morality, and the relative charm of the smells of coal dust and camel dung.

A certain man high up in the Dartmouth Administration told Professor West that he began this book because of the author, but he finished the book because of Mr. Cunninghame Graham. The compliment is a pretty one because it is apt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDeath

February 1933 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleA PRACTICING LAWYER

February 1933 By George M. Morris 'II -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

February 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1926

February 1933 By J. Branton Wallace, Ritchie C. Smith -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1933 By Frederick William Andres, Mace Ingram, Bill Keyes

Books

-

Books

BooksFACULTY PUBLICATIONS

March 1920 -

Books

BooksRETURN TO CASINO.

MARCH 1964 By HARRY T. SCHULTZ '37 -

Books

BooksLAUGHTER AND TEARS.

FEBRUARY 1972 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Books

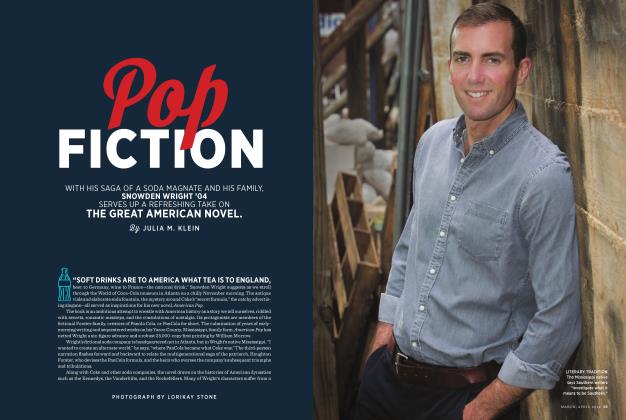

BooksPop Fiction

MARCH|APRIL 2019 By JULIA M. KLEIN -

Books

BooksIMAGINATION.

JULY 1963 By RALPH A. BURNS -

Books

BooksTHE IROQUOIS EAGLE DANCE AN OFFSHOOT OF THE CALUMET DANCE.

February 1954 By ROBERT A. McKENNAN '25