By GEORGE W. ELDERKIN 'O2. Princeton University Press, 1924.

The search for origins has, most fortunately, not been confined to the field of biology. In the last half century the aim of enlightened scholarship has been the widening of the historical horizon, the extending of that horizon back to centuries hitherto only vaguely surmised, the destruction of emotional prejudices, and, perhaps the most important of all, the annihilation of obscurantism in all fields. Professor Elderkin's book, one of the "Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology," is a contribution to this general movement.

Taking as the spirit of his book the sceptical utterance of Epicharmus, "Remember to disbelieve," he proceeds, in a series of essays of varying length, to deal with the most primitive religious experience of man and with the expression of this experience in artistic form. Not the least valuable characteristic of the book is the equating of this religious life ot the ancients in its various manifestations with the modern religious practices derived from them, a process which points out clearly and strikingly the essential unity of all human civilization. To the average reader the most interesting and perhaps startling, thing about the book is the way in which so much of our Christian ritual is shown to have its origins in the primitive nature worship of Dionysus and Demeter, the two great divinities of vegetation, of ever recurring life, and hence symbols of immortality.

Kantharos, the title of the volume, is the symbol of Dionysus, the Greek god of wine Originally meaning "beetle" the word "kantharos" was later applied to a particular style of wine-cup because its shape resembled that of a beetle, according to one explanation. In Egypt the beetle was a symbol of immortality and even in the patristic writings we find St. Ambrose referring to Christ as "the beetle on the cross." So in Greece the kantharos or "beetle-cup," was a sign" of immortality because it was used in the ritual of Dionysus. The kantharos appears frequently on gravestones, some of which are reproduced in this book. Besides the kantharos appear also other symbols of immortality and the after-world, such as the pomegranate, the serpent, the cock, the fork and spade, implements used in the resuscitation and resurrection of plant life and so symbols of immortality.

Professor Elderkin traces the sacrament of the Eucharist back to a preanthropomorphic period of religion in which grain and grapes were themselves considered as gods. With the advent of anthropomorphism the use of the bread and wine continued but their significance changed and the cannibalistic "eating of the god" appeared, ecclesiastically known as transsubstantiation.

These are but illustrations of the nature of the first part of the book. It is, of course, impossible to give an exhaustive idea of the whole work, but so much is typical of the spirit and method of the earlier portions. The latter part of the book is of a purely technical nature and is concerned with the identifying and equating of certain Greek, Roman, Etruscan, and even Semitic deities. These identifications are made chiefly on a linguistic basis and the author himself refers to his "etymological vagaries." The roots do at times seem a bit Protean!

Though the book is largely of an esoteric nature the layman will find much in it to stimulate his thinking in channels all to" little employed. Being a pedagogue and realizing that this review may be read by a reasonably large group of Dartmouth graduates, 1 cannot refrain from expressing the hope that the reading of Professor Elderkin's book ma) lead to the reading of extended works on the subject, such as Sir James Frazer's "The Golden Bough" and Miss Jane Harrison's "Prolegomena to the Study of the Greek Religion."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleWHAT ARE THE TRUSTEES DOING?

June 1924 By Lewis Parkhurst '78 -

Article

ArticleMATERIES MEDICI

June 1924 By Edwin J. Bartlett '72 -

Article

ArticleSaturday Morning Session

June 1924 -

Article

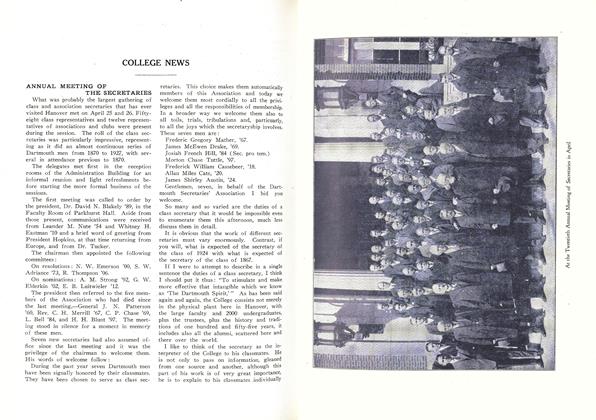

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE SECRETARIES

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleThe Responsibility of the College to its Alumni

June 1924 By P. S. M. -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1903

June 1924 By Perley E. Whelden

Royal Case Nemiah

Books

-

Books

BooksALUMNI PUBLICATIONS

February 1939 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

JANUARY 1967 -

Books

BooksAlumni Articles

OCTOBER 1967 -

Books

Books"Portraits of a Half Century"

January, 1926 By Edwin J. Bartlett -

Books

BooksSOCIETY AND SELF.

JULY 1963 By LLOYD H. STRICKLAND -

Books

BooksGOLDEN MOMENTS IN AMERICAN SCULPTURE.

OCTOBER 1967 By WINSLOW EAVES