A Poem in the Dartmouth Tradition

THIS HAS been the most exciting year of my life, precisely because it has been marked by that freedom needed both for philosophical reflection and for creative writing. I have been working on a long poem entitled "Northern April," a poem placed against the background of New England in general, and Vermont and New Hampshire in particular; it roves back through time to capture ghosts of Indians and early settlers, it deals with the founding of the College, the clearing of land in preparation for the establishment of a hill-dwelling culture, which in turn flourished and died out from the inability of timber and agriculture to support it. It deals with early lumbering days on the Connecticut River, so far as I have been able to reconstruct them from infrequent written accounts and from the memory of living persons; and through it all courses the full-blooded enthusiasm, the lyric note of power, which Dartmouth alone fosters, which Dartmouth has trained in me.

The priceless advantage I have had calls for results above the ordinary, and I hope to convince those who placed their trust in me that I have not been idle. Moreover, going a step farther, I should like to assert that what I have accomplished this year is a combination of original research and creative experience which heightens and intensifies the value of that research, so that the work of the entire year, when I have finished it, shall be in perfect balance. The discipline required to carry out such a program must be of the most rigid sort, that kind imposed from within.

The undeniable advantages of the Senior Fellowship, as I see them, lie in the fact that it gives the independent mind a chance to operate independently, instead of confining it either to the pedestrian pace of the dull class, or to the grooved track into which many teachers direct their charges, with high marks as a reward for those students who most faithfully mirror the professorial bias. The disadvantages are of two kinds,—first, the purely mechanical limitations which experience has pointed out to me; second, the added responsibilities, perils, and hardships of the man blazing the trail. There is no doubt whatever in my own mind about the unique value of the educational opportunities offered to Senior Fellows at Dartmouth.

If I had space and time I should like to attempt to prove that independence, far from being antisocial, is the highest possible form of cooperation; that an original point of view logically presented is what every teacher should require of the ideal student. The ideal class would demand of the man behind the desk, I am convinced, this very pioneer force and courage, coupled with a large tolerance. It is obvious that enthusiasm is an emotion as constructive as fear is destructive; therefore a discipline based on the former of the two emotions will produce work of better quality in all respects. It is greatly to be deplored that no system of marking has yet been invented which, discounting abnormally developed retentive or imitative faculties, will equate insight and originality with high grades.

The scholarly side of my work as a Senior Fellow has been a careful survey of culture in Ireland in all its aspects, from the earliest times up to the present day. My method of study has been that employed by the students in the Experimental College at Wisconsin; I have devoted a year to the examination of one important civilization from such widely differentiated, yet closely knit, points of view as Anthropology, Art, Architecture, Sociology, History, Music, Literature, and Religion. Once a week I meet my tutor, Professor David Lambuth, and read a paper which I have prepared from material gathered throughout the week. I often exercise my privilege, as a Senior Fellow, of attending classes, and find that many of them have a bearing on what I am trying to do. For instance, a course in Central and South American Indian Cultures gives me a valuable approach, a sociological one, and provides actual facts which may be shelved in my brain against the time when I shall need to compare Mayan burial customs with the burial customs of the ancient Celts. In the process of writing a chronologically arranged account of culture in Ireland, I find that my plan of attack must vary from vertical cross-section to horizontal survey, that many of the topics I have chosen show a tendency not only to interpenetrate and to combine with each other, but to shed astounding light in my mind from as yet but dimly perceived horizons. It is difficult at times to restrain the activities of research within their original boundaries, but I have tried to do so, and to keep accurate notes, in addition to the compilation of a bibliography. At the end of the first semester I had proceeded as far, chronologically, as the year 1600; during the rest of this year I hope to examine critically the literature written in English which has come out of Ireland. Much of the most vigorously beautiful poetry and prose written today in English is the product of outlawed Irish pens.

And the products of my own pen, they have been chiefly poetry. My aim has been to make it poetry of a high order, worthy of endeavors into which has gone the sum of my hopes, experiences, and dreams. As I stand on the summit of my twenty-one years and look back I see a great deal of kindness and love, for which I am grateful; but in addition to that I perceive the bewildering complexity of events out of which I have woven the fabric of my inner life, and it is the color of these experiences that I would attempt to fix upon the printed page. I think I may accomplish this better by poetry than in any other way, yet it is not through direct narration that such effects are to be achieved, for facts baldly presented grow tiresome, like a long procession of uneventful days; in fusing together all the various conflicting elements of my personality, finding meaning in life, I try to communicate that meaning to others. Meaning, truth, reality—it does not matter by what name it is called—to my way of thinking may be apprehended more completely through an indirect than through a direct approach. "Suggerer, viola le reve!" When we look at a Cezanne canvas, we see the essence of all trees and hill-sides that have ever been; we are amazed by the grace of a Degas dancer, and to our eyes the flowers that Renoir painted, and the voluptuous women, are more sensuous than any to be found in real life. None of these great artists made the mistake of a direct approach. Art as imitation will never seriously challenge art as interpretation.

Suggestion, then, the oblique approach, is to be desired, but it is successful only when the artist is fortified, first by a sufficient body of unique, intuitively grasped and comprehended experience, secondly by the sheer technical power to recreate this experience in such a way that the resulting ambiguity contains transcendant meaning.

The poetry printed here is the first section of my long poem, "Northern April." The pace of this first part comprising about one-third of the total number of lines, is rapid, the colors brilliant, the predominating theme, sounded toward the beginning and repeated in the last few lines, is contained in the words time has no meaning. Each of the sections resembles the movements of a symphony. The setting is New Hamphire and the time the present. My own peculiar form of blank verse, alternating, as a rule, masculine with femine endings, and varying in tempo according to subject, prevails throughout.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH MEN IN AVIATION

April 1933 By Carroll A. Boynton '33 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1933 By Harold P. Hinman -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

April 1933 By Rees Higgs Bowen -

Article

ArticleNorthern April PART ONE

April 1933 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1902

April 1933 By Hermon W. Farwell -

Article

ArticleTHE UNDERGRADUATE CHAIR

April 1933 By J. S. Monacan'33.

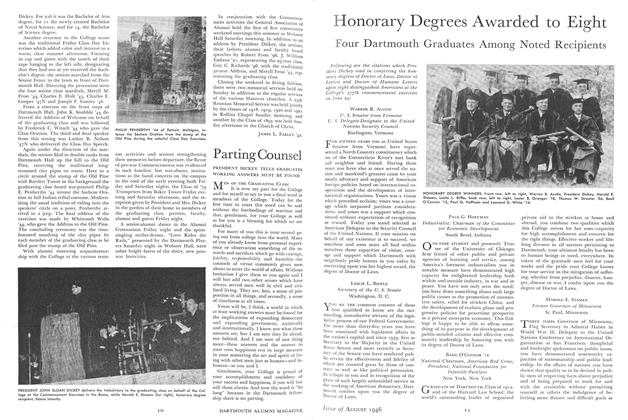

Kimball Flaccus '33

-

Article

ArticleUTOPIAN SCHOLARSHIP

April 1933 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleWhiteface, New Hampshire

December 1942 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Article

ArticleBlind Man's Buff

August 1946 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Feature

FeatureGOTHAM GAMBIT:

December 1956 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33 -

Feature

FeatureTHREE POEMS

January 1958 By Kimball Flaccus '33 -

Article

ArticleTwo Poems of England, Long Ago

NOVEMBER 1970 By KIMBALL FLACCUS '33

Article

-

Article

ArticleFaculty Activities

April, 1911 -

Article

ArticleStudents Garry World Issues to Town Groups

May 1950 -

Article

ArticleBridge Honors Knights

May 1961 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1966 By LARRY GEIGER '66 -

Article

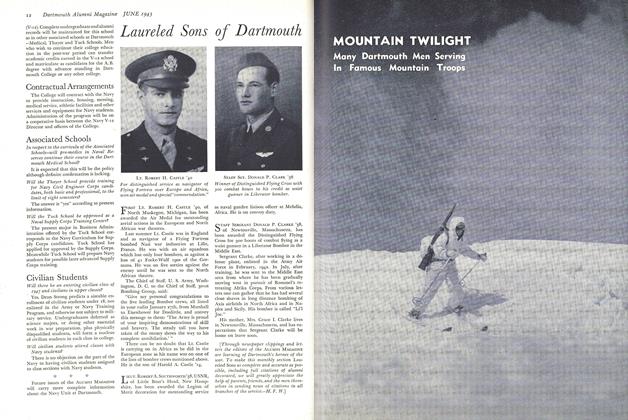

ArticleMOUNTAIN TWILIGHT

June 1943 By LT. CHARLES B. MCLANE, '41