BILL BREYFOCLE '27, in a recent letter, recommended a biography, The Smithof Smiths, and two novels, both important, Malraux's Man's Fate, a powerful and exciting novel of the communist uprising in Shanghai in 1927, and Romain's many volume novel Men of Good Will.

Last month I wrote Briefly on Edward Garnett. This month in connection with South to Cadiz (Harper and Brothers, N. Y. 1934), I want to say a few words about H. M. Tomlinson.

This book supposedly concerns travel, but in reality it is a Tomlinson monologue about himself and his relation to his times. Mr. Tomlinson might just as well have taken a bus to Upper Tooting, for I believe his reactions would have been about the same. He had been asked by the Manchester Guardian to report the London Economic Conference, but he refused and went to Spain instead. Nevertheless he did report, it is true only in broad terms, this conference and there is little of the essence of Spain in his book. For this the reader might far better reread DonQuixote, George Borrow's The Bible inSpain, R. B. Cunninghame Graham's Aurora La Cujini, Salvador Madariaga's Englishmen, Frenchmen, and Spaniards, or better still his The Genius of Spain, or even Unamuno's The Tragic Sense of Life. Yet Mr. Tomlinson is a great travel writer as witness his famous The Sea and theJungle, Tide Marks, London River, Giftsof Fortune, and Under the Red Ensign. How to account for South to Cadiz? For as a travel writer I fear Mr. Tomlinson is getting threadbare.

I have long been an ardent admirer of Mr. Tomlinson, and, in fact, have all his books, and once knew him well enough to break bread with him at his table. Furthermore I shall go on recommending the above books with my last breath, and yet I cannot get steamed up over this last book of his. Mr. Tomlinson, I suspect, is a little tired. I remember that his voice is low and sounds as if it came from far away. He is one, among many, who suffered acutely, in a spiritual sense, from the war, and there is no one that I can think of who has written better on it. Illusion, 1915 partakes of the very essence of the unreality of the "Western Front; Waiting for Daylight has the sharpness and trenchant irony of one who saw and felt (in Joseph Conrad's sense in his preface to The NigSer of the Narcissus) the tragedy of ten million wasted lives. The disenchantment that he felt then he feels now, twenty years later. There has been nothing since to alleviate his feelings (katharsis), but a

great deal to increase his bitterness. He is, perhaps, a little more plaintive, but the groans are still there. They are the groans of a transcendentalist, of a gentle humanitarian trying almost in spite of his intelligence \to have faith in the goodness of human nature, living in a naturalistic world. Thoreau has not been his mentor for nothing. Mr. Tomlinson is essentially a tender-minded man, and I say this with nothing derogative in mind. Unfortunately for Mr. Tomlinson the writer, however, he has lost his sense for the fact, for the con Crete natural object, for the smell of things, and a growing passion for abstractions, for a sort of personal and introspective metaphysics, does not make for a great travel book. One notes this change in his novel The Snows of Helicon which must be judged a failure. He is shocked by our politicians, by our economics, by our merchants of death, and the elasticity of a youthful rebound has left his spirit. (It is difficult, too, to locate any sense of humor in him.) In this South to Cadiz he contributes an admirable essay on Thoreau entitled The Road to Concord, and it throws a good deal of light on Tomlinson himself. As a man Mr. Tomlinson may still be loved; as a writer he is losing his grip. If true, this is a shame, but after all we have had from him all anyone can expect from one man. The books listed above are among the finest books of our time, and if you do not know them, you have missed one of the most delightful treats that in my experience as a reader I have ever known. The war did many in, and among them Mr. Tomlinson. There is little, it seems, for him to do now save to cultivate his garden. It is what all optimists and idealists are forced to do in the end. Perhaps, as Voltaire hinted, it is a sign of wisdom.

South Street, A Maritime History ofNew York, by Richard C. McKay. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York. 1934.

If you are interested in ships, trade, or American history, this is your book. Readers of Alexander Laing's The Sea Witch,Clipper Ship Era, by Captain Arthur H. Clark, or the more recent excellent Greyhounds of the Sea, by Carl C. Cutler, will find that this book ties together all three. Mr. McKay is the grandson of the famous designer of clipper ships, Donald McKay, and would seem particularly well equipped to write this history.

This is the history of our shipping from 1783 to approximately 1865. These were the years of the packets, the China clippers, slavers, and other kinds of sailingships, but by 1865 steam had already sounded the death knell of the wind jammers, though I remember about twenty years ago being thrilled by a seven-masted schooner (was it the Thomas W. Lawson?) off the Massachusetts coast.

Mr. McKay tells many interesting anecdotes which livens up considerably what might have been a prosaic economic history. I recall an anecdote of one Captain Preserved Fish. One day his boat was hailed by a custom's officer who asked for the name of the ship. "Flying Fish," was the answer. "And the cargo?" "Frozen Fish," was bellowed back through the megaphone. "And the captain?" "Preserved Fish," was the reply. No wonder the custom's officer got hot.

The author writes in a generally straightforward style though he occasionally goes Victorian as witness: "On February one, 1783, Matthew Fontaine Maury laid aside his beloved charts and confidently sailed out across the Unknown Sea to drop his anchor in the Ultimate Haven from which no voyager returns." Which may lead us to confidently assume that he died.

Mr. McKay ends his book with a plea for a United States merchant marine, though what shipping it will carry he doesn't say. He believes that the government should subsidize ships "as an adjunct to our commerce and a vital element in our national defence." It seems to me that many years ago I heard this same plea. Today with diminishing foreign trade and hundreds of idle ships rotting at the ways the plea is weaker than ever.

This is not a distinguished book as literature, but it is informative, and most entertaining.

Glory Hunter, by Frederick Van de Water. The Bobbs-Merrill Cos. 1934.

The author effectively smashes the Custer legend, that I for one, was reared on as a boy, in this impartial and complete biography. Many times my brother and I reenacted with paper soldiers the Battle of the Little Big Horn, and "Yellow Hair" Custer was our favorite soldier, and generally the last to fall. But always fall he did, for we had to be historically accurate, and when he was the last soldier standing, we put a star in crayon on his back.

Glory was Custer's mistress. Much he sought her, and found her forever, the author says, in death. To be a hero in one of the most complete reverses any American regiment ever sustained in action was Custer's lot when he met the Sioux at Little Big Horn. Only a horse, Comanche, survived. The author sketches in rather loose prose Custer's life from his boyhood, through his rather unsuccessful years at West Point, and the cavalry campaigns of the Civil War, to his final exit in Wyoming in 1876. It is a thrilling story and as far as I can see Mr. Van de Water has said the last word on General Custer. It may disillusion you, but here are the facts. My own sympathies must remain with the Sioux.

General Hugh (N.R.A.) Johnson among others objects strongly to the book, but he had better like it, for it rings true in all details.

The Georgian Scene, by Frank Swinnerton. Farrar and Rinehart. 1934.

Some of you may remember Frank Swinnerton when he spoke at Dartmouth about a decade ago. Do you also remember how we discussed his novel Nocturne in Professor Lambuth's English 51? I hope that Professor Lambuth is discussing this latest book by the same author, for it seems to me that it would make excellent collateral reading for any course in modern English literature.

Ms. Swinnerton, as author and publisher's reader, has had a wide acquaintance among English writers, and his experience of many years with manuscripts (he read, for instance, Lytton Strachey's original typescript Eminent Victorians) qualifies him to write this survey of English writers from Henry James to Joyce and Eliot. It is a most entertaining book and I am grateful to John Farrar for asking him to write it.

His discusses critically, and by the nature of the book often superficially, with summaries of certain books, and with minor biographical material enlivened with anecdotes, some seventy-five different authors, men and women, who have written during, and a few years before, the reign of King George V. For the most part it seemed to me that his comments are acute, fair, sensible, and enlightening, and written with the persuasiveness of one who knows of what he writes.

Swinnerton writes with candor and with a professional suavity that could only come from one who for many years has been active in the writing business, and who knows that most writers have feet of clay.

I missed any estimate of Theodore and Llewelyn Powys, Henry Williamson, H. A. Manhood, Colonel T. E. Lawrence (who, though he doesn't write fiction must be reckoned with among the great Georgians), Hugh Munro, George Blake, William Plomer, Roy Campbell, and several others. He underestimated C. E. Montague, and if he included such old-timers as Wells, Shaw, and Barrie, why not include Henry W. Nevinson? However, he couldn't mention everybody, and considering everything Mr. Swinnerton has written one of the most sprightly and entertaining books of the season.

Prelude to the Past, by R. G. William. Morrow and Company. 1934.

This autobiography has a racy quality about it that will appeal to the modern man or woman. The dust wrapper modestly states that "this intimate and very frank story of a woman's life is like a novel —except that it's true." It isn't much like a novel, but it is amazingly frank and probably true. I confess that when she called one of her lovers "Kobra" I reached for of soda. Fraulein Rosie Graefenberg has about as much reticence as the Albert Memorial, but it must be confessed that reticence is not the prevailing fashion in modern confessional autobiographies. However, it ill befalls a pedagogue to cavil at such trifles in this interesting story of a modern woman who "has been everywhere, seen everything, knows almost everyone."

As the book jacket says, "You may have met her .... attending some Senate hearing in Washington, or following the Massie Case (trust Rosie to be there) in Honolulu; dining among diplomats at the Crillon, or in an apron cooking some favorite dish over her own stove (the Home Beautiful touch)." Thus she will undoubtedly appeal to travellers, auditors of Senate hearings, people who frequent gaudy trials, those who are fortunate enough to know the Crillon, and the great mass of people who are moved by persons in aprons cooking their favorite dish over their (very) own stove.

Saunterer's Rewards, by E. V. Lucas. J. B. Lippincott Company. 1934.

This is a charming, modest little book of essays written by the living authority on that prince of essayists, Charles Lamb.

Red Heifer, by Frank Dalby Davison. Coward-McCann. 1934.

You may not believe that the story of a cow can be fascinating reading but this book proves that this is so. It is a gripping story of the wild cattle that roam the back ranges of Australia. An excellent story for man or boy.

This novel won the Australian Literature Society's gold medal for the best Australian novel of the year.

Oliver Cromwell, by John Buchan. Hodder and Stoughton, London. 1934.

This book is all a good biography should be. Judicious, well-balanced, and most competently written, Mr. Buchan has given us a full length, three-dimensional portrait of one of England's greatest men. There is no bias whatever in this book. The author makes clear Cromwell's weaknesses, but he indicates his genius as well, and he helps to clear Cromwell's reputation from the heated attacks of many partisan biographers.

In the early seventeenth century, England was in a transitional stage and Cromwell played with genius his prophetic part in England's crisis. Cromwell's frequent, pious, and fervent invocations to God were quite in character with his Puritan background. It seemed to Cromwell that God was on his side, and it would almost seem so to the reader of his amazingly successful military campaigns so well delineated by Mr. Buchan in this book.

Natt Emerson 'oo liked this book, and I agree with him that it is a more solid piece of work than Mr. Buchan's excellent life of Montrose of some years back.

The Riddle of Jutland, by Langhorne Gibson and J. E. T. Harper. Coward-Mc-Cann. 1934.

This book attempts to solve "the riddle of Jutland" (who won and how?), and so establish Admiral Jellicoe as one of England's greatest sea fighters. After many conflicting reports and the suppression of facts by the Admiralty at Whitehall, the British public had made the aggressive David Beatty the hero of the battle. However, the authors claim, that the years that have now elapsed since have disgorged so many facts that we now know that the Battle of Jutland is "synonymous with the name of Jellicoe and with British victory." It is very possible that the partisanship of the authors for Jellicoe vitiate to a certain degree the historical ac ;uracy of their picture. I suspect, however, that we shall not get much closer to the truth than in this book. Jutland was a complex affair, and like many naval battles, many of its intricacies may never be known.

In the welter of books about the fighting and heavy losses in the land forces, particularly in the infantry, one often forgets how great are the losses in modern sea fighting. When the Queen Mary went down at Jutland (off the coast of Denmark south of Skagerrak) through the explosion of her too-exposed magazine after a direct hit, 1258 officers and men went down with her and only 17 were saved. In the same battle the Invincible sank with Vice-Admiral Hood and "only six of her company of 1034 escaped with their lives."

Who won the Battle of Jutland? Britain lost 14 ships, with a total tonnage of 112,000, and 6,094 men; Germany lost 11 ships, of 60,000 tons, and had 2,551 dead. England remained master of the North Sea, and the Great German High Seas Fleet except for one unavailing sortie, remained bottled up in their harbors until the mutiny of the sailors at Kiel in 1918, and the subsequent surrender at Scapa Flow. I can guess that the German high command simply didn't dare gamble on a great German sea defeat. This was their great mistake as they must have realized when they surrendered their fleet. Messrs. Gibson and Harper contend that the important thing was "not ships sunk, but ships ready to go on fighting, determined the victory." The day after Jutland the British fleet patrolled the waters as if nothing had happened. They continued to do so until the end of the war.

For an interesting fictional account of Jutland, from the German angle, I recommend The Sunken Fleet (Little, Browti and Cos.), by Helmut Lorenz, Commander on Admiral Scheer's flagship Friedrich derGrosse. This is an exciting story and it sounds reliable. The German sailor's morale was badly let down because of the High Command's policy of keeping the fighting fleet of Germany safe in her harbors. Herr Lorenz explains all.

Burmese Days, by George Orwell, Harper and Brothers, N. Y. 1934.

Many months ago I read a striking and honest book Down and Out in Paris andLondon, by George Orwell. Evidently he has drifted out to Burma, for no one could have written this who hadn't soaked himself in Burmese life, who hadn't known the lassitude produced by the rainy season, the terrific sun of the dry periods, and who wasn't familiar with the life of the "pukka sahib" administrators and their native underlings. This book is literally saturated with atmosphere and if it isn't authentic I'll bet on the next Yale game.

The novel was recommended to me by Bill Eddy, a Princeton man, and one of our most popular professors. Incidentally Bill knows India himself, and said that this picture of British rule in India might well be a true one though it was not necessarily typical. Administrators are like U Po Kyin, subdivisional magistrate of Kyauktada, in Upper Burma, and Mr. Macgregor, Deputy Commissioner, Ellis, and Flory, while the others who carry the white man's burden reek with authenticity.

With intrigue in native politics as a background, Mr. Orwell has written the story of the defeat of Flory, who in a valiant attempt to marry a white woman to save himself from complete dissolution, ultimately meets his fate as a sahib should; and of the lives of a group of Englishmen, of their "club" life, of a native insurrection, and of the triumph of a corrupt native magistrate over a struggling native doctor, one Veraswami. That the magistrate's triumph is short lived is no sop for the happyending reader as none of the characters are worth much of the reader's sympathy.

Here is northern Burma to the life. If you like to read of far off places as they are, this is your book. Orwell has a flair for the truth, and the ability to write it down. Highly recommended.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

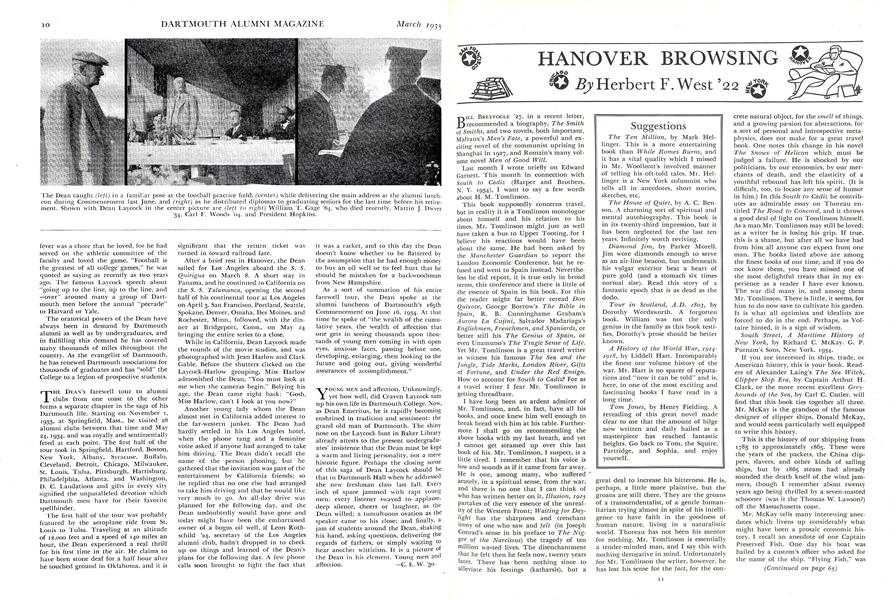

ArticleGraven Laycock: A Dartmouth Tradition

March 1935 By C. E. W. '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

March 1935 By C. Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

March 1935 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Article

ArticleTwenty-Five Years Ago

March 1935 By Hap Hinman '10 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

March 1935 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

March 1935 By Harold P. Hinman

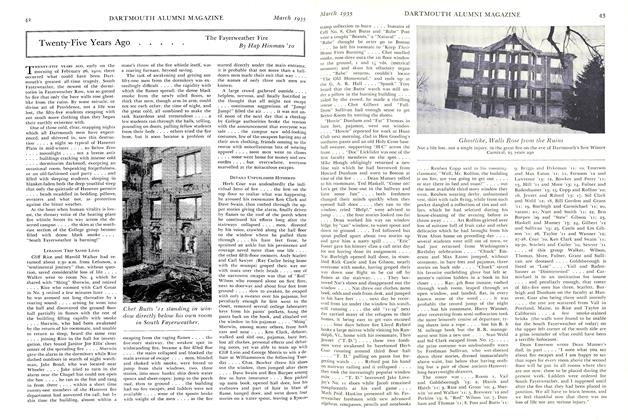

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1931 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksLEG MAN

April 1943 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Books

BooksKEEP YOUR HEAD DOWN

June 1945 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1946 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleAtlantic Odyssey

April 1943 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Association to Observe 100th Anniversary Next Month

May 1954 -

Article

ArticleSwimming

JANUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleMy 3" x 5" Boondoggle

DECEMBER 1966 By Robert E. Asher '31 -

Article

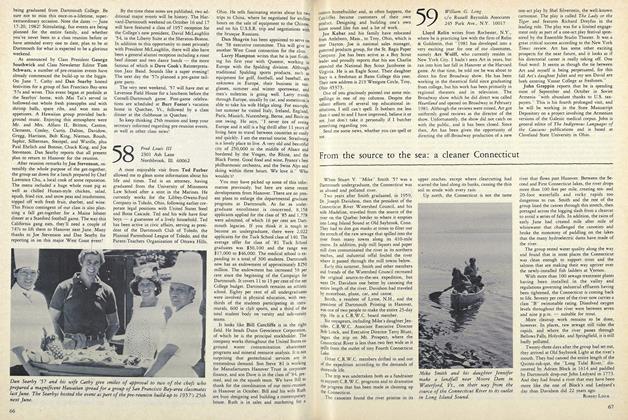

ArticleFrom the source to the sea: a cleaner Connecticut

NOVEMBER 1981 By Robert Linck -

Article

ArticleAbout 25 Years Ago

February 1937 By Warde Wilkins '13