Address at the opening of Dartmouth College, September 22, 1927

Among the many thoughts which are appropriate and desirable for such an occasion as this, time is available for the enunciation of but a few. It is, however, needful that no man enter upon his work within the College without consideration of some of these. It is indispensable alike for the achievement of the meritorious purpose of the College and for the conservation of the welfare of the individual man that certain points be emphasized. Attention should be given respectively to the service which the College can render to social welfare and to the personal benefit which may accrue to the individual man from articulating himself with this aspiration.

Truth is the ideal of education, as it is of religion. An ideal world would be a world in which all men sought knowledge and all which purports to be knowledge would be true; in which all men would intelligently seek to know the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth; and, knowing it, would strive to live in conformity with it.

It is to accelerate progress towards such an ideal that the College was founded and lives. Understanding of and reverence for the spirit of truth is the influence which the College strives to radiate. Eagerness that the College shall radiate such a spirit should come to be the insistent desire of every undergraduate who enrolls within it. To such extent as this wish remains absent from any undergraduate's mind, or even undefined, the potential ability of the College to realize its highest possibilities is weakened, as is its capability to be helpful to the individual student.

This is the basis for the assertion which I will make dogmatically,—that any man who enters upon, or continues, his course, viewing it as a task to be done, rather than as an opportunity to be utilized, ought, in fairness to the College and in deference to his own selfrespect, to withdraw from an association he does not understand and to the spirit of which he will not be helpful.

Much has been said, and rightly said, as to what the American college owes to the undergraduates, individually and collectively. The discussion, however, has begun to be somewhat more of a clamor than a debate, and it is essential for the good of society which the college serves, as well as for the value available in the college to its individual members, that we return to some emphasis upon what the undergraduate owes to the college. The relationship is one of mutual dependence and mutual obligation. The college officer or the college student who ignores this fact should be displaced.

The American college is an institution devised and developed for the needs of American life. It is beside the point to appraise its values in its own environment on the basis of its similarities or dissimilarities to educational institutions in other settings among other peoples. Its mission is the development and cultivation of an educated citizenry.

Its origin was in the desire of the Puritan commonwealth for an educated ministry in the Christian churches. The tablet on the Johnston Gate at Harvard University carries quotation from contemporary records as to the purposes which led to the foundation of America's first college, in these words:

"After God had carried us safe to New England and we had builded our houses, provided necessaries for our livelihood, reared convenient places for God's worship, and settled the civil government, one of the next things we longed for and looked after was to advance learning and perpetuate it to posterity, dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches when our present ministers shall lie in the dust."

The subsequent development of the American college was an expansion of this responsibility for a limited service to a responsibility to provide for educated members of the bar, educated physicians, educated engineers, educated business men. Now, within a decade, it has been called upon to educate a representative constituency for the good of the American people at large.

Meanwhile, also, the American college has come to be looked upon as an available and desirable agent "for the developing of leaders within all realms of public and private affairs. Increasingly we have heard about the obligation of the college to develop intelligent leaderships for all of the various needs of contemporary life.

This is justifiable if we interpret the term "leadership" sufficiently broadly. It is all wrong if we restrict its meaning to super-men. The gist of this matter cannot be better stated than it was in a baccalaureate address of President Birge of Wisconsin a few years ago, who said:

"Many writers today argue that colleges ought to select and train their students with a primary reference to leadership. I have never taken part in this discussion for I have been content that the University of Wisconsin should train its students to think and to work,'— that it should fit them for public service arising out of work well done. If these results are attained, I have been ready to allow the question of leadership to be settled—as it usually is settled—by time and by nature. Yet in the sense that my words carry today, leadership is one of your social duties; it is also a duty for which you have been trained. I do not mean that you are to assume the direction of affairs; I am not talking about anything which will get your name into the newspapers, or you into the legislature. These results may come or they may not, and for most of you they are not likely to come. Your chief work for the public will be through inconspicuous service to your fellows. But in that service there is an element of leadership —often unconscious on the part of both leader and led—which every community, every state, must have if it is to be prosperous and happy. This is the leadership of those whose lives have been nourished from the great central sources of the world's life which the University possesses —from letters, from science, from knowledge applied to every side of life's activities. It is the leadership of those whose souls have been raised to a higher level by their years in the University, and who so live in after years that their neighbors are conscious of the fact. It is the leadership of those who in their turn direct the eyes of others to the light which the University can furnish, who extend the vivifying influence of the University to their own communities, who thus enrich the life of the state as they help to create the larger campus."

If it be asked why constantly there need be so much said about what the college is for and what it ought to do, reply must be made that it is because of the fact that conditions within the college and without the college are never the same in one time and another. Robert Louis Stevenson, in "Lay Morals," makes analogy between life and the shadow of a great oak. "The shadow," he says, "lies abroad upon the ground at noon, perfect, clear and stable, like the earth, but let a man set himself to mark out the boundary with cords and pegs and were he never so nimble and never so exact, what with the multiplicity of the leaves and the progression of the shadow, as it flees before the traveling sun, long ere he has made the circuit, the whole figure will have changed."

So it is with education. The accurately drawn figure of a given moment may be descriptive of little existent in the next. The relation of shade to light alters continuously from year to year. It is consequently incumbent upon the college, from time to time, as frequently as possible, to examine the figure it has drawn of what education is and often to make revision of its concepts of what its own artistry must portray.

Always for the college there is the increasing task,—something to be added to that for which it has been responsible before. Today it cannot lessen its emphasis upon the need for depth of knowledge, while asserting its increased extent, without stultifying itself. As well, it cannot betray the cause of the graduate school, which depends upon the college for preparation for specialization and research in restricted fields.

Yet, in our time as never before, the college must, in justice to the needs of society, emphasize the areas of knowledge, as well as its profundities. Particularly must it insist upon the importance of human experience in modifying doctrinaire hypothesis. Further, it must relate thinking to the realities of life. The possibilities of thought for thought's sake alone are soon exhausted. This proposition is early to be consigned to the limbo of useless, if not degenerate, things.

Today, the world is handicapped even more by lack of men with sense of proportion and sense of the relationship of one phenomenon of life to another than it is by lack of men of erudition in specialized branches of knowledge. Ignorance of the relationships of knowledge may be found as evident and as dangerous among men learned in specialized fields as it can be found among those who are ignoramuses in all fields. The only available agent within our system of formalized education for giving thought to this condition and for making effort to correct it is the college.

Mankind is constantly misled and often has suffered grievously from its instinctive inclination to believe without proof that authorities in restricted fields of knowledge are wise in all. The great mind which functions with superb efficiency in the field of economic production, but generalizes fallaciously in regard to the uselessness and ineptitude of historical study, is no more astray from reality than may be the scholarly social scientist who contemns machine production, in disregard of its ultimate possibilities for adding to the comfort and to the happiness of society at large.

Count Keyserling has spoken upon this point in "The World in the Making." He says, "Because only the rarest among the gifted recognize their 'natural sphere of action,' and not because they might be too one-sided, do so few amount to anything in the history of humanity; in undertaking something more or something other than in them lies, they impair their own creative function, for the productivity of a faculty depends wholly on its proper adjustment to the core of personality and the surrounding world accessible to it."

In its interpretation of what education really owes to contemporaneous needs, the college must concern itself today with the limitations of specialized scholarship in interpreting the scope of knowledge.

Furthermore, the time has come for us to say in our colleges what many of us acknowledge to ourselves,—that there is fully as much need for a constituency educated to choose its leaders as there is for educated leaders themselves. Particularly is this true if we hold democracy to be a desirable form of social organization, or if we believe in it as a form of government in political affairs.

Much speculation is given to the question whether we have in these times men as capable and as wise as were the leaders of old. If we are inclined to pessimism at this point let us in fairness recognize that the field of knowledge has so incredibly expanded and the intricacy of affairs has become so inconceivably involved that it requires men of deeper insight, wider intelligence, and more active imagination than ever before to render service comparatively significant in our day to that which was rendered in former times by leaders in the respective periods of accomplishment.

If we conceive of leadership in terms of power, we are not lacking evidence in contemporary life that in individual men this quality still persists and that authority can be seized and held and exercised by a Mussolini or a Lenin. If we hold leadership to be influence that wins affectionate confidence and fires the imagination of men, we have for contemplation the figure of a Gandhi with a greater following than any man has ever had in his own life-time in the world's history.

In distinction from these, we have among all peoples other men of discriminating judgment, intellectual power, and spiritual conviction, who have all the potentiality needful to great leadership but whose very greatness holds them from seeking it or seizing it. Meanwhile, ignorant or irresponsible constituencies withhold from conferring it upon them. One trouble with representative government, for instance, is that it is too repre sentative. I have come, therefore, more and more to the conviction that it is not so much qualities of leadership in individual men that the world lacks today as it is - the intelligence, the desire, and the will of the public that leadership shall be intrusted to these.

Consequently, I have come to distrust the validity of much of what has been said, including much which I have said myself, in regard to its being the function of higher education to train for leadership. I ask permission to revise this statement to say that the first function of the college is to educate men for usefulness.

For more than a century, mankind has been accepting more widely each day the principle that the voice of the people is the voice of God. This has resulted in an undiscriminating confidence in the infallible worth of public, opinion in regard to any specific issue, while it has resulted disastrously to many, in their instinctive reverence for the tenets of religion. We maintain the forms of delegated responsibility but in practical operation, we demand that our legislators, our courts, our churches, and our schools shall be subject to the popular will of the time, however ephemeral or capricious this may be. Practically, and acknowledgedly, that man is held to be a more eligible candidate for high position in state, or church, or school, who has done little, good or bad, than is the man who has done much, if some of this has been, as it must inevitably have been, contrary to the popular will.

It is trite to repeat the statement that man's growing mastery over the material world has so far outstripped his knowledge of the laws of human relationship, or, indeed, his desire to know these, that progress in the latter realm is infinitesimal as compared with advance in the former. It is worthy of more than idle consideration, indeed, whether man's enlarged dominion in the fields of physics and chemistry has not introduced a hazard to the social state beyond man's ability to control.

With man's escape .from the domination and repression of the church in the search for scientific knowledge, the way was opened for an inconceivable advance in knowledge of natural laws and for the utilization of these in accordance with his desires.

Man, however, has not escaped, nor in the present temper of the public mind is he likely to be released, from attempted domination by conventional minds of his thinking, his speech, or his deeds.

The influences to restrict and to suppress thought or experimental action on the part of those who would be pioneers in the field of social or political relations are as marked, on the one hand, as, on the other, is the encouragement for and endorsement of experimental research in the fields of science.

In the large, mankind is not possessed of any desire for light or guidance as to how it may discover truth in regard to theory or practice essential to improved conditions in human relationships. He is almost as little willing to allow consideration and discussion of how possible safeguards may be erected against future catastrophe.

Meanwhile, throughout society, mutual suspicions and mutual establish what amount to professional types of mind whose affiliations preclude clear reasoning. Men adopt attitudes and take positions on current issues not so much in recognition *of the merits of the specific questions involved as in accordance with the prevailing thought of their respective economic, intellectual or social castes.

Thus, the world comes to be filled with people with causes to defend or with theses to maintain, regardless of facts pertaining to the individual case. Those desirous of light to reveal what causes are worth-while defending or what projects are worth-while espousing are few in proportion to those who resent evidence which conflicts with opinions they already hold, whether from belief, prejudice, or instinct, or the dictates of self-interest.

The influence of a college education ought to be that men should desire as complete knowledge in regard to the merits of what they do not believe as in regard to those opinions which they hold as convictions. Mutual respect between men of conflicting views ought not to be notable by its complete absence among men to whom opportunity has been offered for mental cultivation. If something of forcefulness were lost, a more than compensating gain in reasonableness would be secured. The possibility, under such conditions, that occasionally a man should be led to change his mind ought not to be held by him or by the community as dangerous to self-respect or antagonistic to the public welfare.

Macaulay, in his essay on "The Earl of Chatham," speaks of the characteristics of the Whig and the Tory, each "as the representative of a great principle, essential to the welfare of nations. One is, in an especial manner the guardian of liberty, and the other, of order. One is the moving power, and the other the steadying* power of the state. One is the sail, without which society would make no progress, the other the ballast, without which there would be small safety in the tempest."

For any among you familiar with sailing, who have been rendered helpless in a calm or brought near to catastrophe in a storm, the analogy will not require elaboration. In any helpful theories of social progress we must respect the values of sail and ballast, alike.

If it seems to some of us that the ship of social welfare is in danger of being over-dressed with sail, the arguments for attention to the need of ballast must needs deserve careful investigation. If to others of us it seems that in the imperatively desirable voyage to some safe harbor, time is the essence, the argument for further .spread of sail should not be lightly disregarded.

Surely, among educated men it ought not to be held that all merit, except in most infrequent circumstance, will be found wholly in one attitude or another.

This seems to me to be the quality of the spirit of tolerance which the college should crave in its men, not that they should lightly abandon conviction and belief, but that they should be willing to examine the validity of their beliefs in the light of all possible data bearing upon these. Meanwhile, I would add, as a personal opinion, that the man with a positive belief, even if a fallacious one, is better than the man without any. Forcefulness has the possibility of becoming intelligent and useful. For passiveness there is little use or hope.

At this point we come inevitably to the question of authority. The weakening of the respect for authority may well be held to be the greatest problem of the present era. Few would argue, even among the extreme malcontents, that all authority can be dispensed with and civilization still be preserved. The unceasing quest among men of intelligence is where authority may be found and for knowledge of the attributes by which it may be recognized.

If all of our thinking is not to end in futility and if all our works are not to be in vain, we must arrive speedily at some working hypothesis, generally accepted, however much it may be held subject to eventual correction. Otherwise, we must end in anarchy and chaos and destruction, and become a generation known for its destructive genius without capacity for constructive thought or cooperative action.

Prince Andre Lobanow-Rostovsky has recently pointed out in an article in "The Hibbert Journal" that authority derived its power for countless centuries from the assumption that it was derived from the Source of Supreme Authority on High and was bespoken through His representatives on earth. "God became more distant and invisible, but the rulers acted and spoke in His name and were considered responsible to Him for their rule."

Prince Rostovsky continues that though definitely dead now, the idea stood the test of seventeen centuries of the Christian era, as well as the many thousand years of the pre-Christian civilization.

He concludes,—

"We find, therefore, at the opening of the twentieth century, humanity drifting into a period of cyclonic changes and revolutions and the crisis of authority, from lack of a solid transcendental basis, has become a crisis of civilisat.on.

"What will be the outcome of this deadly disease? A reversion to the old idea of 'God in Heaven, King on Earth,' is impossible owing to the weakening of religious faith in the masses. The absolute grip over souls that it had a few hundred years ago and its domination in matters secular have vanished presumably for ever. Eoose and slovenly democracies with noisy elections bringing to power men who have no qualifications except skilfulness in electoral tactics, will probably be eliminated by the very force of things, by more disciplined and concentrated communities, whether civilised or barbaric.

"If it is impossible to forecast, still it is the first duty of every thoughtful mind which has witnessed within the last fifteen years a nearly total collapse of civilisation, to scrutinise the problem with the utmost penetration. One may say with certainty that the very life of Europe depends on whether or not out of the present turmoil there will be evolved a conception of authority sufficiently stable to assure the continuity of its development, and broad enough to embrace all modifications of thought and custom which progress will present. The problem offers two aspects: First, the designation of the proper men to exercise power; and, secondly, the endowing of their authority with sufficient moral backing to make it effective."

Herein lies one of the greatest questions of all time. Has our generation an answer? Can education help? What have the men of this college to say?

Finally, for a moment, I would ask my associates in the instruction corps and the students in the classrooms to consider one particular responsibility that rests upon the college. This is that in arguing the need for a sharpened critical faculty among men and a more rigorous attempt to subject all the phenomena of life to a rule of reason, we do not make extravagant and unjustified claims for what rationalization is capable of in explaining life or in determining action.

After the maudlin sentimentality and the simpering emotionalism widely prevalent in the Victorian era, it was as inevitable as it was desirable that reaction should set in and that we should approach the realities of life with less posing and more genuineness. It was likewise natural that this process should be particularly emphasized within our colleges, even perhaps until all enthusiasms should be dulled, all emotions scorned, and all aspiration weakened, when these could not be clearly shown to be sponsored by the intellect. This development, however, has clearly passed the point of its greatest usefulness. Now, in turn, the colleges should be the first to accept and to proclaim this fact.

Professor Sumner has enunciated a fundamental truth in "Folkways" that our colleges sometimes ignore: "Book learning is addressed to the intellect, not to the feelings, but the feelings are the spring of action."

The American college was conceived and established by men deeply imbued with the spirit of self-sacrifice and permeated with a sense of responsibility for enhancing the public welfare. The gifts of material resources and the consecration of personal careers to college service through centuries since have been inspired by like motives. It has been for the sake of influencing the body politic through men eager for the public good, as well as through men intellectually competent, that colleges have been founded and have been sustained during lives of increasing strength. The student or the officer of the college who ignores this fact or resists response to the "feeling" of an institution is misplaced within its ranks.

Hence, the college has responsibility to cultivate the feelings as well as the minds of its membership. Its atmosphere is as important as its curriculum. The careers and accomplishments of its graduates will be affected not alone, nor perhaps most largely, by specific knowledge which they have acquired. Their disposition toward life, so far as college influence goes, will be determined by the extent to which their feelings have been refined and tinged with sense of responsibility during undergraduate years. Herein lie the incentives to action and the wellsprings of inspiration among college men.

In spite of the dangers of generalization, I, with deliberation, make this one. If the only options available to this college were to graduate men of the highest brilliancy intellectually, without interest in the welfare of mankind at large, or to graduate men of less mental competence, possessed of aspirations which we call spiritual and motives which we call good, I would choose for Dartmouth College the latter alternative. And in doipg so, I should be confident that this College would create the greater values and render the more essential service to the civilization whose handmaid it is.

Lecky, the great expounder of rationalism, discussing the limitations of reason, says, toward the close of his "History of Rationalism in Europe,'- "Utility is perhaps the highest motive to which reason can attain. The sacrifice of enjoyments and the endurance of sufferings become rational only when some compensating advantage can be accepted. The conduct of that Turkish atheist who, believing that death was an eternal sleep, refused at the stake to utter the recantation which would save his life, replying to every remonstrance, 'Although there is no recompense to be looked for, yet the love of truth constraineth me to die in its denfense,' in the eye of reason is an inconceivable folly; and it is only by appealing to a far higher faculty that it appears in its true light as one of the loftiest forms of virtue. It is from the moral or religious faculty alone that we obtain the conception of the purely disinterested. This is indeed the noblest thing we possess, the celestial spark that is within us, the impress of the divine image, the principle of every heroism. Where it is not developed, the civilization, however high may be its general average, is maimed and mutilated."

In conclusion, I wish my final word today to be a plea to men of the undergraduate body not to fall into easy misconceptions of what the College wishes to accomplish or of the significance of the processes by which it works. It seeks to be a stimulus to intellectual awakening and heightened mental power. It aspires to be an agency by which men may be induced to think. It cajoles ability, not to flatter it but to give it selfconfidence. It flays ignorance, not in contempt for those condemned to it but in solicitude for those who may avoid it. It questions conventionality, not because convention is predominantly wrong but because convention is not always right. It challenges belief, not that belief shall be destroyed but that it shall be made strong.

Today the traditions, the attainments, the resources, the strength and the power of the College are made available to you. Utilize them! And as soon as may be, come to understanding of them!

A Palaeopitus Initiation at the Old Pine

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDICK'S HOUSE

November 1927 By Eugene Francis Clark '01 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorEditorial Comment

November 1927 -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1899

November 1927 By Louis P. Benezet -

Article

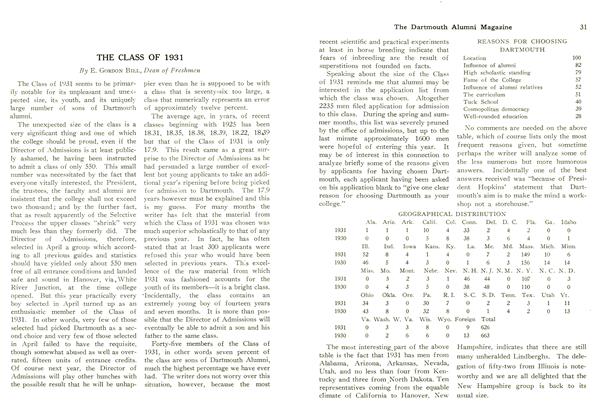

ArticleTHE CLASS OF 1931

November 1927 By E. Gordon Bill -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1911

November 1927 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesCLASS OF 1921

November 1927 By Herrick Brown