FOR some months past I have had a delightful correspondence with Mr. Paul Lemperly, of Lakewood, Ohio, who is one of the best known of American bookcollectors. His recommendations I have found to be as sound as those of any critic that I happen to know. Some of his recent recommendations are David Cecil s The Stricken Deer, a life of that charming and eccentric poet William Cowper, and Earl ham, by Percy Lubbock, who also wrote one of the best critical books on the novel in English, The Craft of Fiction. Other favorites of his are R. B. Cunninghame Graham, the late Neil Munro, author of Doom Castle, The Lost Pibroch, etc., John Buchan, Neil Gunn, as well as the old reliables Thomas Hardy, Henry James, etc. I hope that I may be able to pass on to you in future issues some more of his suggestions.

I have been informed by one who should know that Mr. Hopkins is very enthusiastic about the novels of Kenneth Roberts. Prof. Malcolm Keir joins the procession, which includes many of the administration staff,,faculty, and students. So it may be fitting if I tell you a little about these books, so that you, too, may join the procession, if you have not already done so.

Arundel, Rabble in Arms, The LivelyLady, and Captain Caution, by Kenneth Roberts. Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc.

Dartmouth conferred her highest literary degree on Kenneth Roberts last Commencement in early recognition of his accomplishment in becoming the finest American historical novelist of his generation. After reading Rabble in Arms I can think of no-one who deserves the accolade more than he.

Arundel is a story of Maine men in the War of the Revolution told by one of them, Steven Nason. The locale is the Abenaki country in Maine stretching from Kennebunkport north and west along the Kennebec River. The main part of the book deals with Colonel Benedict Arnold's route through the wilderness, of his unsuccessful attack on Quebec, and of the gallantry and hardihood of his ragged army. Most of the famous revolutionary characters are here, including General Washington. There is a love story interwoven with the historical events of the book. Steven Nason, as a callow youth, falls in love with Mary Mallinson, who is captured by one Guerlac, and carried off to Quebec. Her image remains in Nason's memory, but when he meets her finally in Quebec in a highly exciting situation the truth is revealed to him, and he realizes that all along he had been in love with someone else. Hook and Guerlac are villains of the deepest dye, and they with Marie de Sabrevois (Mary Mallinson) are too melodramatic to be convincing. However, the remaining characters are real enough, and the author, most careful and painstaking in historic facts, background, and atmosphere, knows of what he writes. Behind them all stands the enigmatic figure of Arnold, but not Arnold the traitor: "He was a brave and determined man, nor was there any soldier serving under him who would not, at his request, follow him anywhere, at anytime." (Page 514-515) Later Roberts writes (Page 619): "A brave and gallant gentleman who, if it had not been for the terrible thing that later happened, would be acknowledged by all soldiers to be second only to George Washington in daring and brilliance in military matters. (Washington, according to his friend Thomas Jefferson, and other critics who served with him, was most prudent and slow to act in military matters.) He had all the qualities of a great soldier .... if the commissioning of officers had been in the hands of General Washington, where it should have been, instead of in the hands of the petty little argufiers of Congress, Benedict Arnold would never have suffered the cruel injustices that were heaped on him until, weakened by wounds, he was coaxed or driven to his awful crime."

This book and Rabble in Arms is really the saga of Arnold. Here he is at last vindicated.

Rabble in Arms, the best of Robert's novels, carries on the story of the Revolution and tells of Arnold's great struggle at Valcour Island in Lake Champlain, and of the final victory over Burgoyne at Saratoga, waged against the odds of a trained British soldiery, a stupid and divided Congress, jealous officers, poor equipment, and most hostile weather. Steven Nasori, Phoebe his wife, Cap Huff, and the lovely spy Marie de Savbrevois, appear again. One of the characters, who plays a fairly important role because of his knowledge of the Indian tongues, went to Eleazar Wheelock's Indian School. Mr. Roberts did some of his research here in Hanover, and as usual, everything to the finest detail is as accurate as historical research can make it. The incredible sufferings and courage of the "rabble in arms" makes it clear that the revolution was won in spite of our inefficient government, in spite of the fact that more than 50% of the country was Tory (my estimate), and in spite of the inevitable graft, jealousy, and blunders of certain American officers and politicians. Mr. Roberts does a convincing job in the apotheosis of Arnold and his "rabble." The topography, the plans of the various battles, the kind of boats and how they were built, are accurately given. A most readable book and the best historical novel by an American that I have ever read.

The Lively Lady is not as ambitious a project as the previous two books, nor is Captain Caution, his most recent novel. They are, one might say, breathers after the immense energy that it must have taken to write Arundel, and Rabble inArms.

The Lively Lady tells of the adventures of Richard Nason, son of Steven and Phoebe, during the War of Impressment, from 1812-1815. Nason, the captain of his own brig, is impressed by the British ship Gorgon, escapes, becomes captain of a privateer with a commission from President Madison, sails down the eastern coast of the United States, captures several vessels, crosses the Atlantic, cruises in the Bay of Biscay, sinks the Gorgon, is captured in a fog, and is imprisoned at Dartmoor. The description of prison life at Dartmoor under "King Dick" is the best part of the book.

Captain Caution is another exciting chronicle which concerns Daniel Marvin, an Arundel mariner, Corunna Dorman, daughter of a sea-captain, a Frenchman Argandeau, wise about women, with the exception of his wife, and a great fighter, Lurman Slade, villain of the piece, liar, slaver, blackmailer, but a man of courage like Hook of Arundel, and Matthew Newton, a Harvard man. The story is laid in the year 1812 and relates many adventures, the highlights of which are: imprisonment in a British gun-brig, the capture of the brig, Marvin's fight with "Little White" aboard a British prison-ship, and his final capture, aided by his Gangway Pendulum, of Slade's brig off Madeira.

The author tends to make the English too villainish, and the Yankees too noble. Actually both were of the same breed, and in general tarred with the same brush. See the late Harold Murdock's little book The Nineteenth of April, 1775, and you will see what I mean.

Twilight in the Forbidden City, by Sir Reginald Johnston. D. Appleton-Century Company, New York. 1934.

This is a long book of almost five hundred pages. The first ten chapters are an exposition of the history of the Manchu dynasty from the Reform Movement in 1898, through the revolution of 1911 when the Chinese Republic was established, to the expulsion of "The Boy Emperor" from the Forbidden City in Peking (i.e. the palace of the Manchu emperors) in 1924. This part of the book I found to be the most informing, for from the monarchical point of view Sir Reginald knows this better than any foreign Chinese historian. The remainder of the book gives a rather detailed account of Sir Reginald's association with the young emperor P'u Yi in the capacity of tutor. This I found rather boring, save on occasions when the author touches upon certain aspects of Chinese history of the last ten years or so.

One's judgment of the book is naturally biased by his point of view. Sir Reginald's point of view may be gleamed from this random passage (Page 179): "By 1919 that 'Deity' had condescended to lower himself from the order of divinity to that of mere humanity, and was popularly known to foreigners as 'the Boy Emperor.' Nevertheless there were many Chinese then, and much later, to whom he was still the Lord of Myriad Years, the Son of Heaven, the de jure ruler of the world." The author is indubitably pained by the fact that China became a republic. He quite rightly says that the name of the government means very little and it is the spirit underlying the name that counts. It is possible to imagine more liberty under a constitutional monarchy, like England, than in a democracy, like the United States. Be that as it may, Sir Reginald hoped for a constitutional monarchy in China and got instead the chaos of a republic. One further suspects the impartiality of the author when he learns that he was British Administrator of Weihaiwei during 1917-18, and Commissioner during 1927-1930. He is an old-fashioned nineteenth century English imperialist, like Cromer and Curzon, and was unquestionably serving that cause officially when he was unofficial tutor to P'u Yi. What he wanted was this very ordinary young man restored as Manchu Emperor under the guiding sword of Japan. A republic was only one step from a Soviet China and this neither Japan, England, nor Sir Reginald could stomach. When the Japanese enthroned P'u Yi as "Puppet Emperor" of Manchouko in 1932, Sir Reginald insists that he went of his own free will. "The Dragon had come back to his old home," as Sir Reginald puts it. Unfortunately the world took a different view which was, briefly, that Japan was grabbing Manchuria from China using the rather pathetic little P'u Yi as a smoke screen. Sir Reginald served their cause well. He went into "conference" with Chang Tsolin, who was the Japanese agent in Manchuria, and he "rescued" P'u Yi from the Chinese, probably saving his life, and put him into the Japanese legation in safe keeping until he could be installed in Manchuria by the Japanese. That Sir Reginald is somewhat of a snob makes little difference, for it simply makes him one of us. Hobnobbing with royalty was ever a major ambition of English and Americans alike. This book will please Japanese propagandists, but it will have less appeal to those who hope China may work out her destiny along liberal principles.

I might add that Sir Reginald goes into some detail about the court life of the Manchus. It makes the court life of Louis XIV, of glorious memory, resemble a Sunday school picnic. The late Dowager-Empress was a great hater, and is perhaps the most fascinating character in the book.

C. P. Scott, by J. L. Hammond. Harcourt, Brace & Co. 1934.

Many Americans read the ManchesterGuardian, and it seems fair to say that no other newspaper in English, or in any other language, has had such a great international reputation. For the most part this is the creation of the late C. P. Scott, who died in January, 1932. Soon after leaving Balliol College, Oxford, Mr. Scott joined the Manchester Guardian in 1871, and served it faithfully for over fifty years. His idealism, which he expressed in a letter written on Feb. 26, 1871, continued until the end of his life. It is the attitude of one who merged all his ambition and pride throughout his life in this newspaper. He wrote: "I cannot tell you, my dear dad, how happy it makes me to feel that I have a great and noble field of work before me, where I may fail or may succeed as failure and success are counted, but where at least I can go on without doubt or fear knowing that if I am faithful all is well. This, no doubt, is true of life always and everywhere, but one is able to realize its truth more deeply when one's immediate objects lie outside oneself, when personal success, however legitimate, makes up but a very small instead of a very large part of one's hope for the immediate future." He once thought of becoming a Unitarian minister and his moral purpose and driving sense of duty, familiar to us in the example of the Adams family, never left him. He never pandered to advertisers and the paper became and has remained a great moral leader.

This book by Mr. Hammond is the story of the Manchester Guardian, and as Mr. Scott was the Manchester Guardian, it is his story in the light of the great events of recent English and European history. He spoke vehemently against the Boer War, he encouraged Women's Suffrage, he followed like a hawk the War and the treaty, and fought courageously for a wise and generous peace; he bitterly opposed his friend Lloyd George in his policy in Ireland after the war, and without fear or favor spoke the truth as he saw it. For many years Mr. Scott wrote the "leader" for the paper, and in doing this Hammond writes, "Scott had a patient and deliberate mind; he was interested in a problem through his intellect before he was interested in it through his emotion; his natural treatment of any question was the dispassionate analysis of fact and argument." He surrounded himself with able men. The best writer on the Guardian was unquestionably the late C. E. Montague, who married Scott's daughter, and who will remain famous for his best of war books Disenchantment, for his wise dramatic criticism, and for his charming essays. Mr. H. W. Nevinson served as foreign correspondent at various times. Loyalty to the paper, and to its editor, was as natural as it was intense. Mr. Scott was, on the whole, an optimist. His favorite lines in poetry were written by Coleridge:

"And winter, slumbering in the open air, Wears on his smiling face a dream of spring."

Then A Soldier . . . . , by Thomas Dent. John Day, N. Y. 1934.

Bob Coltman '32 was so enthusiastic about this book that he had a review copy sent to me. One is struck, first of all, by its candor and frankness. The author uses occasionally, and often with comic effect, certain monosyllabic Anglo-Saxon words, which have not yet attained general use among genteel society. He is not trying to shock, but finds these words the only ones that he can use to get his desired effect. He writes intimately not only about himself but about living people, so he has adopted a pseudonym. I thought it might possibly be William Plomer but I am told my guess is wrong. It is not our Tommy Dent. The book lacks a certain masculine quality which accounted at first for a small suspicion that the book might have been written by a woman but I do not seriously suggest this.

The book is an autobiography. Objectively the author looks back on three Tommys (for one changes physically every seven years), the first Tommy up to the age of seven with the setting in South Africa, the second Tommy up to the age of fourteen with the setting of an English public school, and the third Tommy up to twenty-one, with the setting of England and Oxford during and after the war. The book ends with his rather startling marriage. His analysis of childhood and boyhood is extremely good. Mr. Dent not only knows child psychology but he has an amazing good memory. The South African childhood is as wild as you would expect. His father reminded me somewhat of the late D. H. Lawrence, and he died when the boy was very young. The author spends many pages, among the best in the book, in describing the awakening of sex curiosity, and Tommy the third is finally seduced by one Rosune, who has three children, and is almost old enough to be his mother. His own stern and sacrificing mother seems to do the boy as much harm as good in the clash between their two points of view. She dominates the book and her ambition and self-sacrifice for the boy is typical of many mothers. Tommy becomes a conscientious objector, is imprisoned, has a severe physical breakdown, and finally returns to Oxford. Before the war this book might have been considered bad taste, but as the Zaharoffs have said, much blood has flowed under the bridges since then, and in spite of certain portions of the book, we may read it without any undue shock to our sense of good taste. Well worth reading.

A Journey into Rabelais's France, by Albert J. Nock. William Morrow, N. Y. 1934.

Wishing to pay my respects to Mr. Nock's urbanity, his pungent asperity, and his erudition, I shall say that he is "not a man of genius, certainly, or even of first-rate talent, but sensitive, able, highly educated, experienced, humorous, gravitating naturally towards the best things that the life around him has to offer." This description with but one word changed, has for had, is taken from Mr. Nock's description of Ausonious, and after reading this book, and two others of his, I feel that it describes Mr. Nock pretty well, too. I am glad to be able to pay him this compliment.

Back of this urbane and piquant travel book through the Rabelais terrain, lies thirty years' acquaintance with France and its civilization. Also, with Catherine Rose Wilson, Mr. Nock has recently edited a new edition of the Urquhart-Le Motteux translation of the works of Francis Rabelais, so Mr. Nock is eminently qualified to write delightfully of Rabelais, and of Touraine "the garden of France." He has done so, to my taste at least, in this book. Claiming modestly to be an enthusiastic Pantagruelian myself, I thoroughly enjoyed it. His route, roughly, was from Chinon through Touraine, Provence, the Islands of Hyeres, to Lyons and Metz.

The quality of Mr. Nock's mind may, perhaps, be judged from a few quotations. "Thus," he writes, "Puy-Herbault's book started the tradition which has come down to the present day, and is still widely accepted, that Rabelais was a low-lived drunken scoundrel, given over to the most degrading vices, a profligate fellow who knew neither the fear of God nor any decent respect for man. It seems odd that such a yarn as this could ever have been swallowed by anybody who had read Rabelais's works however inattentively, but it has been swallowed by whole generations; for verily the human gullet yawns wide for slanders, and the human craw's capacity for them is without limit." (Page 84.) Again he writes: "The most that can be said for Rabelais on this score (i.e. his unsavory reputation) is that he was an experienced man of the world, completely at home in any society, of highly cultivated tastes, singularly objective and free from prepossessions. Otherwise, he was a highly serious person, known and praised as one of the best physicians in Europe and one who held very responsible positions; and in addition, a scholar and man of letters second only to Erasmus." (Page 187.) And lastly in speaking of a picture by Jordaens, among drawings by Ingres, Mr. Nock writes, "it was as striking an effect as one can imagine would be produced by a distinguished-looking person in an audience at the Metropolitan opera, or by an honest man in Congress." (Page 197.) Mr. Nock is that delightful creature; a man of prejudices. Protestantism and some of its more obstreporous manifestations, French cigarettes, French trains, certain aspects of the American scene, post offices in France, are some of his pet hates. Thus the man is an individual, has color, speaks his mind, and is not a wishy-washy intellectual. All authentic Rabelasians, and they must be legion, will find this a delightful book.

Miss Robinson's sixty-three pen-and-ink drawings add to the book's charm. They are good, but not inspired, drawings.

For Rent in Hanover Seven Room House North End February and March Box 714 HANOVER, N. H.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1932

January 1935 By Charles H. Owsley. II -

Article

Article"DARTMOUTH: A GOOD RELIGION"

January 1935 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

January 1935 By F. William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

January 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

January 1935 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1904

January 1935 By David S. Austin, II

Herbert F. West '22

-

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

December 1938 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1944 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

June 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1953 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Books

BooksPENN STATE YANKEE

December 1953 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1957 By HERBERT F. WEST '22

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHAYER SOCIETY OF ENGINEERS

December 1924 -

Article

ArticleSecretaries Take Notice

MARCH 1930 -

Article

ArticleJust Twenty-Five Years Ago

December 1934 -

Article

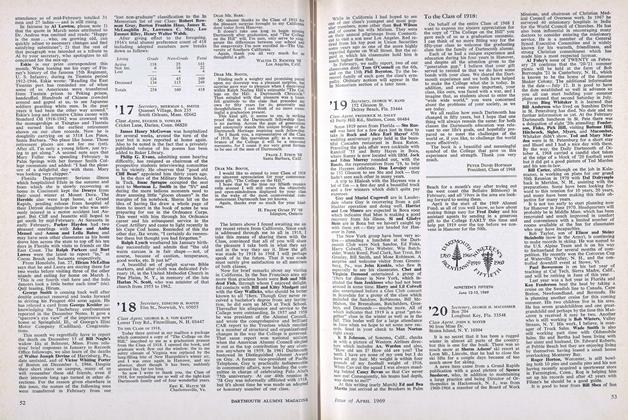

ArticlePresent and Proposed Alumni Council Districts

April 1940 -

Article

ArticleFinite Math

APRIL 1994 -

Article

ArticleTo the Class of 1918:

APRIL 1969 By PETER DAVID HOFMAN