I. Eleazar's "Robe, Casok and Half"

UNDOUBTEDLY THERE is something abnormal in the make-up of those who, like myself, enjoy rummaging through the records of the past, with an itch for bringing to light events and happenings of no importance. Such persons must certainly be classed with the Paul Brys, who may even become Peeping Toms if not restrained by the inhibitions of generations of ancestors imbued with the New England conscience, or, perhaps, by a healthy respect for the penal code. Nevertheless, pursuing an elusive clue through a maze of manuscripts and arriving finally at the solution of a problem which is absolutely without significance, has its attractions. Consider the following:

In the voluminous collection of Wheelock manuscripts in the College archives is the following letter, written by a member of the class of 1774.

Sutton, May 29th, I774

Rev'd & honor'd Sir,Permit me the Liberty and Freedom to trouble youwith a few lines in the multiplicity of your Affairs justto inform you from orders and directions received ofmy class Mate Kendall I have on your accompt employ'dMr. William Dawes of Boston to purchase you a prunella Robe, Casock and Hat, the Robe and Cassock Iconvey you by the Barer hereof, the Hat I shall bringyou myself, ire

I am with all Duty, Rev'd Sir your mostobedient pupil and very humble ServantCornelius Waters.

This letter is not calculated to arouse much interest beyond some vague wonder as to what "prunella" may be, and an idle speculation upon the feasibility of employing the present generation of undergraduates, with their confirmed habit of week-ends out of Hanover, to run errands for the President and faculty. It is true that the letter may indicate an early use of academic costume, revived, so far as it relates to the faculty, only as late as 1908, with the main purpose, so the younger teachers inferred, of doing away with Professor Hitchcock's straw hat, which was beginning to show the strain of exposure to the rain and sun of some forty Commencement processions. But probably Eleazar's robe "was clerical rather than academic.

However, real interest begins to be excited by a letter from Wheelock to Dawes dated July 30, 1774. Eleazar did not like his new garments.

My dear Mr. Dawes

I rec'd the Robe ire which you sent by Waters mypupil. And hoped for an opportunity to have sent itback by Mr Chase's Team, but I find he has so plan'dhis Journey that it Seems to be impracticable. I haveseveral objections against that habit viz, that I think.theprice is too high for a Garment so near worn out, butthat I believe I should have got over if it had been themantle of Elijah, but I understood it had been baselyforfeited, andd I chuse to be excused so much as puttingit on, as 1 am not willing to be the Conservator of Sucha Alemorial.

I shall take the first opportunity to convey it to you& shall be willing to make any reasonable reward foryour Trouble, and am with much affection and respectYour Sincere Friend & humble Servant

Eleazar Wheelock

This is reinforced by a second letter from Wheelock, dated October 5, 1774.

My dear Sir.By Mr. Walcutt I return the Habit you sent me andI heartily thank you for your kind design to Serve meand havent the least question of the Sincerity of yourFriendship therein and determine you Shall not be aSufferer by me for it—But there is so much Smutt comeswith the Garment, and the Country is so tempered orrather distempered as that I have not thought it expedient So much as to put it on, nor can I do it withoutdisobliging my Friends. If it had been the Mantle ofElijah or good Doctr Seawell there would have been noprevailing Objectioti against the Garment but much theContrary. I am sorry you are disappointed in a kind design to Serve me—I have Sent you a Guinea by theBearer and Shall be ready to do anything that becomesa Gentleman and christian in the Affair, As Sdon as youShall let me know what it is. I heartily Wish your Prosperity outward and Spiritual and am with Sincere Affection & Esteem

Your very hearty Friend and Humble Servant

Eleazar Wheelock

These letters are definitely intriguing. In what respect did the garments fall short of the requirements of the "mantle of Elijah"? Where, when and why did they accumulate the "Smutt" referred to? Why would Eleazar's friends turn from him in horror if he should put them on? We get a clue in a letter from William Dawes, dated December 8, 1774. After recapitulating the contents of the letters which he had received from Wheelock he goes on to describe the transaction in the following terms.

now Sv after receiving this ballance (it wasL6.13-4) i stand ready to do all in my power to serve you,in particular respecting the Robe, Cassok and hat, butwith your particular direction therefor, either to sellthem at privat of publick sail, as you shall order, i aprehend Sr you think yrself Disgraced by the above Garments being purchased for your Use, i believe there wasno such design, i can speak for myself as inosent, Mr.Kendal knows i offered to Lend the money to buy newCloth & assisted him in looking for the same, i knewnothing of Mr. Lock's Garments till Mr. Kendal informed me of them, if desired me to go with him to Cambridge to view them, and as he is at home will give (youa) tru relation of the whol proseeding, i hope he willremember his having an order from Mr. Lock to Mr.Sewall for the sail 6- Dilivory of said garments & all soordered that Captn Marvel who made tham should valluthem, i having nothing to do in the affair but to executeMr. Kendal's order & to advance the Cash, now ST Judgyou if it be right to insist on my takeing them to myselfor in yr makeing my mind uneasy, i must tell you Sv iwill not reecive them as my Goods, if you will not keepthem Deliver them to Mr. Kendal who must take themb- pay for them if you refuse, i am at a Loss to know howto Conduct, som times i think you would be glad iwould make yT resentment, publick but as yet i have notmentioned it but in a privat way to a friend or two, yTswith Duty & Respect

Wm. Dawes

Here is definite progress. With some eagerness we turn to the career of President Lock of Harvard, but encounter a blank wall. President Quincy in his History of that institution, is reticent, not to say coy. He states that the administration of Lock was ' short and not particularly successful," and that he retired voluntarily. Other historians of Harvard and the biographical dictionaries are equally non-committal, but always with the suspicious statement that Lock retired voluntarily," as though the normal exit of a Harvard President was to be thrown bodily from his position by a force not his own. While we have our suspicions, we are really little further on.

Stirring events were now taking place in Boston. The beginnings of the Revolution were at hand, and William Dawes was making Paul Revere's ride; that is, joining Revere soon after the start, Dawes actually reached their destination, Concord, while Revere, after leaving Lexington, had been captured and held. Unfortunately for the fame of Dawes his name adapted itself less well to metrical treatment than did that of Revere. So, while Longfellow found it fairly easy to indite the melliferous jingle,

Come, listen my children and you shall hearOf the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

had he been compelled to fit the name of Dawes into his rhyme in some such way as this,

Come, gather my children all, becawsI'm to tell of the ride of William Dawes,

the "poem" would hardly have become the household word that it did to the children of my generation. Everyone, then, has heard of Revere, but few have heard of Dawes. He also suffered from the rigors of the siege of Boston, and from the fact that he could not collect his debt from Wheelock. Writing from Marlborough, October 9, 1775, he renews his request for payment.

. . this morning Saw Mr. Ben* Walcut, he is after aDeserter, by him i hear of yT Late Journey this wayshould have rejoiced to have seen you, i hope these willfind you safe home in health. Oh ST how has a RighteousGod Reversed things, with respect to myself i have nohome at Boston nor anything there i can Call my own(that once i had somthing handsom), iam now a Resident at Marlborough with my wife & 2 Children, atboard at the house of Deacon Simon Stow, have nothingto support us but my Debts, yv Small one would be received very Graitfully, i am perswaided that nothingbut the want of an Opportunity will prevent yT kind &needful assistance in the payment of yr Debt an Acct ofwhich is inclosed, my wife and children have been hereall sumer, myself left Boston ye 7ofSSen,pn, my love toMrs. Walcut, i saw her brorther Col Marshall the Daybefore i left the town, he is somewhat indisposed, Cantobtain Leave to Leave the town, he is about the town asUsuall, Let his house and is at board, i am incapassatated to do any Sewing. ....

gut the financial stress under which Wheelock labored at this time prevented the payment of any such impressive sum as L 6.1.4, even if he had considered the debt to be just. So, as far as we can learn, Dawes retained permanent possession of the "garmants." Perhaps his great-great-grandson, Charles G. Dawes, former VicePresident and Ambassador to the Court of St. James, has them yet among his family heirlooms.

But the mystery of President Lock remains unsolved. Six months after accumulating the above information, in going through another manuscript collection, a letter from Nathaniel Whitaker to Wheelock, dated Salem, Mass., December 10, 1773, comes to light. In a postcript he says,

You will doubtless hear of the unhappy state of President Lock who has left the Colege & retired to his country farm on account of having been too free with hismaid—Lord what is man left to himself. He is chaff before the wind of temptation.

So the mystery is solved. Further we find a letter written two weeks later from Portsmouth by David McClure, Wheelock's disciple. Its tone of smugness and lack of sympathy for a sister institution in distress is highly blameworthy, and in all probability is to be ascribed to the fact that McClure was a graduate of Yale rather than Dartmouth, but it adds to the evidence.

We have a dreadful specimen from Cambridge of thecorruption of that once pure fountain—this unhappyoverture will very probably be an advantage to Dartmouth & open the Eyes of people—l find the most loosein principles & practice prefer our College to others onaccount of the good order & care that is taken of themorals of the Youth there 6- tho they are wild themselves would chuse their Sons should be brought up ina sober way.

So the story, as a story, comes to a satisfactory and well-rounded conclusion, and the reader who has had the patience to follow thus far will agree with me that its importance is absolutely nil!

A Familiar Gown of Dr. Wheelock's But probably not the controversial robe

Author of "History of Dartmouth College"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

December 1935 By Prof.Nathaniel G.Burleigh -

Article

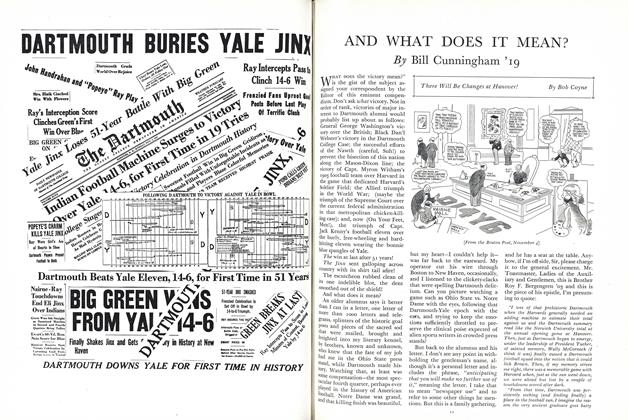

ArticleAND WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

December 1935 By Bill Cunningham '19 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

December 1935 By Edward leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesAll in the Day's Work

December 1935 By Claude T.Huck -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

December 1935 By Harold P.Hinman -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

December 1935 By Josephine C.Chandler

Article

-

Article

ArticleATHLETICS—QUALIFIED SUCCESS

March, 1915 -

Article

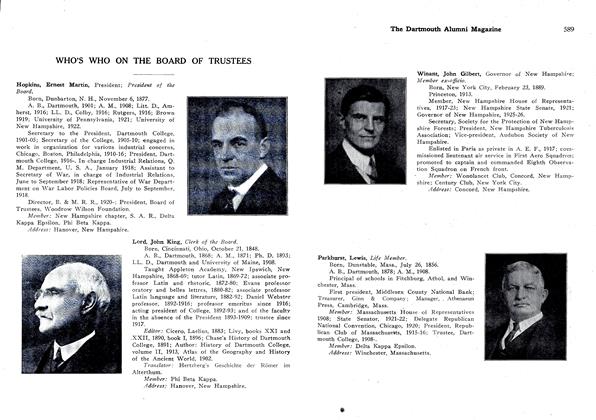

ArticleWHO'S WHO ON THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES

May 1925 -

Article

ArticleMILWAUKEE LACE PAPER COMPANY FOOTBALL TEAM

January 1943 By Captain: C. W. Hamilton. -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SIXTY-FIVE YEARS AGO

March, 1909 By Harvey C. Wood, '44 -

Article

ArticleMedical School

February 1949 By Rolf C. Syvertsen -

Article

ArticleGranddaddy Numero Uno

May 1979 By S.S.G.