Research Work in Physiological Optics Has Resulted in Discovery of Aniseikonia, a New Eye Defect

IT MAY COME as a surprise to many to learn that men and women are coming to the Dartmouth Eye Clinic for consultations from all parts of this country and even foreign lands. How this department of physiological Optics came to be, is a story which begins a long time ago and in an entirely different field. It has been, and continues to be, a never-ending search for knowledge. Endless experiments, with colors and lenses, with cameras and pigments, with eyes and eyeglasses and instruments and apparatus, were painstakingly repeated in an attempt to discover the difference between the eye as a camera and the camera. The study of hundreds of eyes necessitated the development of new instruments to measure them. These instruments led to new and more exact measurements which disclosed hitherto unsuspected variations. And finally, it was discovered that these variations were at the root of some of the most obscure and troublesome ailments to which the nervous system of man is heir.

In 1910, Adelbert Ames Jr., a graduate of Harvard Law School, gave up his Boston practice and turned to painting in which he had always been interested. During the next four years he gradually became involved in the philosophical and scientific aspects of art and its appreciation through the eye as the organ of vision. This led into the study of physiological optics and to Clark University in 1914 to discover, if possible, how we see things. His investigations were interrupted by two years of service in aviation during the war.

In 1919 he came to Hanover to ask the help of Charles A. Proctor, professor of Physics, with his problem which had now become that of measuring the optical characteristics of the eye as a camera in the hope of creating a photographic lens that would have these same characteristics. The visitor was welcomed to Dartmouth and installed on the top floor of Wilder Hall. The work progressed successfully and in 1931 the College made him professor of research in Physiological Optics, and honored him with the Master of Arts degree.

IN THE MEANTIME attempts to obtain proper lens design attracted the attention of Gordon H. Gliddon, graduate of the University of Rochester and a member of the technical staff of the lens designing division of the Eastman Kodak Company. In 1923 he came to Hanover as a graduate student in Physiological Optics to work on "An Optical Replica of the Human Eye," his thesis subject. Rumor had it that "they were working on a glass eye that could be connected to the brain and that this secret would some day startle the world."

The instruments developed to measure the various optical properties of the eye became synthesized into one relatively compact instrument, often in those days referred to as the "Thing" and later called "The Spirit of Hanover." More and more eyes were examined. Improved models of the instrument were built. Precision in technique appeared and data accumulated. Finally, accurate measurements of previously estimated variations became routine and exact correction had thus become possible.

One day the suggested attempt to obtain accurate measurements on the eyes of one who had suffered from intractable headaches, on the suspicion that the symptom might be caused by an obscure eye defect, .provided the first patient. The discovery of the cyclophoric defect and the successful correction of it was the beginning of the clinic, and to the immediate financial aid of this further research development came Dr. Henry Lyman and Augustus Hemingway of Boston.

In the meantime Gliddon, who had taken his doctorate joined Ames as research fellow in Physiological Optics, to form this section of the department of Physics, and other workers were added in the person of graduate students, among them Kenneth N. Ogle. The fame of the work became noised abroad and the top floor of Wilder Hall became a clinic in fact.

Research and clinical investigation developing as two divisions necessitated the establishment of the department of research in Physiological Optics of the Dartmouth Medical School. In 1928 the progress of the work seemed to warrant a first report which was made to the ophthalmological section of the American Medical Association at Minneapolis and which received the bronze medal for "significant application of physics and physiological optics to ophthalmology." The influx of patients began to tax both the personnel of the department and the research quarters in Wilder. John D. Rockefeller Jr., who had become interested in the work, came forward with a most generous benefaction which made it possible to increase the personnel, and to assure the continuance of the work for a five-year period. Leo F. Madigan, an excellently qualified clinician was brought from New York to assume charge of the clinical division and to further the task of applying the research principles and of accumulating additional data. Then Dr. Elmer P. Carleton, a graduate of the Dartmouth Medical School, an ophthalmologist of established reputation and a member of the Hitchcock Clinic, became associated in the work with Madigan. Ogle, who in the meantime as a graduate student had made material contribution to the research in completing his doctorate, was appointed a fellow in the research division. George Agassiz of Boston now made a specific contribution toward the work of the clinical division.

THIS ALL GAVE impetus to the work with the result that by means of the instrument more and more variations in ocular images were discovered and actually measured. This was new and made it possible to take into consideration a defect in binocular vision hitherto disregarded. The image or picture which is formed by the lens system of the eye is focused on the retina in the back of the eyeball much as the image is focused on the film in the back of a camera. This image is carried by the optic nerve on to the brain where the final picture is formed. This is called the ocular image. In eyes which are working right the two ocular images are alike and blend or fuse together to appear as one. In eyes in which ocular images differ in size or shape blending or fusion is difficult or impossible, and is accompanied by nerve strain and fatigue. In extreme cases the brain, as a last resort must suppress one image or turn that eye out of line. This nerve strain or fatigue may show itself in various ways some of which are so strange that they might not be suspected as coming from the eyes at all. Unfortunately, this defect is not necessarily associated with poor vision; it cannot be detected by the most careful refractive examination; and it appears only when eyes are examined simultaneously on the ophthalmo-eikonometer. Because of the difficulty of detecting this defect, called aniseikonia, many a person has wandered from examination to examination without relief, only to be finally classified as neurotic or a little screwy and shunted toward the asylum.

The terminology evolved by the Dartmouth group centers around the root, eikon, a Greek word, meaning image. Iso meaning equal forms, with the root, the word iseikonia which is the term applied to those normal individuals whose ocular images are equal in size and shape. The Greek for negative is an(a) which is used as a prefix to create the entirely new term aniseikonia, the condition in which the ocular images are unequal in either size or shape. The instrument for testing patients' eyes referred to in this article was christened the ophthalmo-eikonometer, or eye and image measurer. Permanent glasses which would correct the condition of aniseikonia would thus be called iseikonic lenses.

AS IN ALL SUCH new developments recognition of the accomplishments of the department has come very slowly. In 1931 there were presented by the department two papers, on the Physiological and Clinical Significance of the She and Shape ofOcular Images, before the American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolarynology at French Lick. There also was exhibited and demonstrated an early model of the ophthalmoeikonometer and shown certain types of corrective lenses. In 193 a the members of the department gave four papers before the New England conference of optometrists in Boston. At that time the department was presented a gold medal for distinguished service to optometry.

With the development of this research in aniseikonia to the point of feasible clinical application a further problem arose. There must come a more rapid routine procedure for designing corrective lenses and a less expensive technical process. The first iseikonic lenses were "fitovers" clipped 011 over the regular glasses and were at best a temporary expedient. This meant that more research must be directed toward the development of a unit lens and Arthur F. Dittmer was appointed a research fellow with this as his problem. Dittmer completed his doctorate in mathematical physics under Dr. Compton at Princeton and came to Dartmouth from the Technicolor Corporation.

With the advent of Dittmer the critical point in the crowding of the top floor of Wilder Hall was reached and the clinical division of the department moved to new quarters in the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital where it functions as the eye section of the Hitchcock Clinic and where consultation for every variety of eye defect is available.

Dittmer succeeded in creating a simplified graphical method of designing iseikonic lenses which could be reconciled with existing technical production methods, and in cooperation with the research staff of the American Optical Company, perfected the unit lens to the point where it did not present anything unusual in appearance. This company is continuing to cooperate with the Dartmouth group in developing new instruments and lenses as they are needed in furthering the research and has accepted the responsibility for making available similar ophthalmo eikonometers for use in other ophthalmic clinical centers. Dr. Julius Neumueller, a very able technical engineer, clinician, teacher and director of the iseikonic division of the Company, has taken up residence in Hanover to keep in touch with the work of the department.

THE MOST RECENT report of further progress was presented by members of the department before the New York Academy of Medicine in April of 1934.

The installation of ophthalmo-eikonometers in other clinical centers has made imperative the establishment of a training course in the technique of the use of the instrument in ophthalmic examination. Several clinicians have already been trained at Hanover. The New York Eye and Ear Infirmary now has on its staff two trained ophthalmo-eikonometric clinicians. There are two in Boston and one in St. Louis. Henry Imus, a graduate of the University of Rochester, with special training in optics and two years experience at Harvard as an ophthalmo-eikonometric clinician, has been added recently to the staff of the eye section of the Hitchcock Clinic to assist Madigan and Carleton in the operation of the two instruments there.

Due credit must be paid to Professor Adelbert Ames Jr. the founder and director of the work, but mention must be made of the remarkable cooperation of the whole group, now twelve men and women, which has contributed tremendously to the growth and success of the department.

In reviewing Ocular Measurements, writ- ten by Ames and Gliddon, Charles Sheard wrote in this magazine, prophetically, in ig2g: "Those interested in vision irrespec-tive of their slant of mind on the subjectand irrespective of their agreement or dis-agreement with the conclusions reached bythe authors, can rejoice with the faculty,students, and alumni of Dartmouth Collegein the fact that research work of this typeand of such far-reaching results has beenundertaken and will be continued, I hope,for many years to come."

Adelbert Ames Jr.

Gordon H. Gliddon

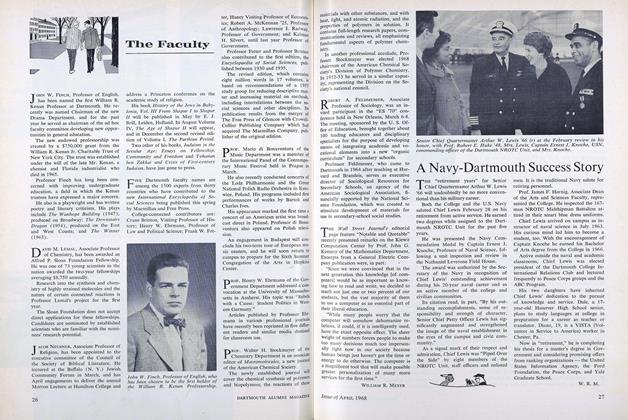

Leo F. Madigan, adjusting the ophthalmoeikonometer, instrument developed at Dartmouth. (Center) Arthur F. Dittmer, staff member. (Right) Kenneth N. Ogle, assistant professor of research inPhysiological Optics.

Research Assistant Imus and Professor Gliddon demonstrating the use of an optical measuring instrument,the ophthalmometer. (Right) Dr. Elmer H. Carleton, whose examination of a patient is the first step in theClinic's treatment.

* During the present year the Department isbeing assisted by a grant from the RockefellerFoundation.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

February 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

February 1935 By Prof. H. F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

February 1935 By Albert I. Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1935 By L. W. Griswold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1935 By Mariin J. Dwyer Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1935 By F. William Andres

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRIZE ESSAY CONTEST IN INDUSTRIAL ECONOMICS

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleSecretary to the President Awarded Dartmouth Degree

July 1954 -

Article

ArticleTHE COLLEGE

March 1961 -

Article

ArticleSoccer

December 1954 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleSNOW ARTISTS

March 1936 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

APRIL 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER