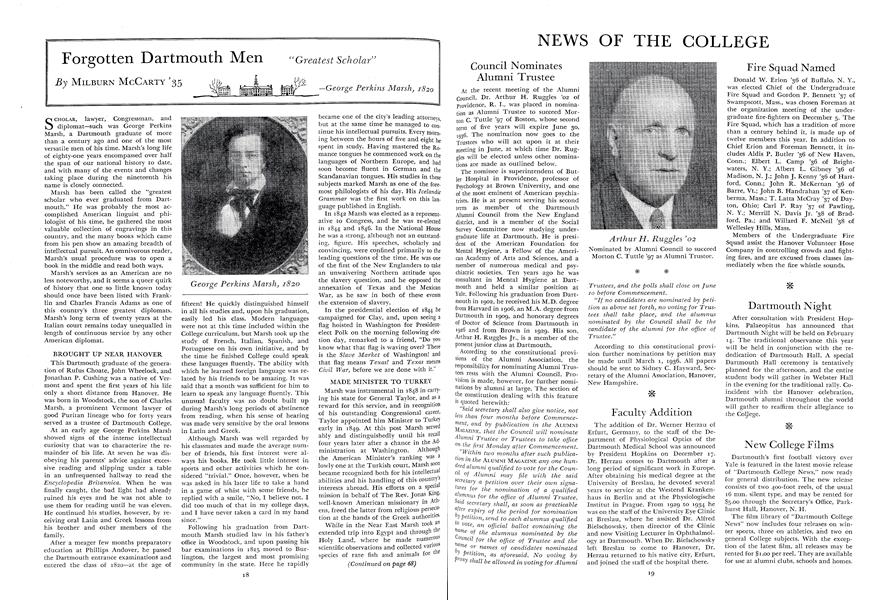

SCHOLAR, lawyer, Congressman, and diplomat—such was George Perkins Marsh, a Dartmouth graduate of more than a century ago and one of the most versatile men of his time. Marsh's long life of eighty-one years encompassed over half the span of our national history to date, and with many of the events and changes taking place during the nineteenth his name is closely connected.

Marsh has been called the "greatest scholar who ever graduated from Dartmouth." He was probably the most accomplished American linguist and philologist of his time, he gathered the most valuable collection of engravings in this country, and the many books which came from his pen show an amazing breadth of intellectual pursuit. An omnivorous reader, Marsh's usual procedure was to open a book in the middle and read both ways.

Marsh's services as an American are no less noteworthy, and it seems a queer quirk of history that one so little known today should once have been listed with Franklin and Charles Francis Adams as one of this country's three greatest diplomats. Marsh's long term of twenty years at the Italian court remains today unequalled in length of continuous service by any other American diplomat.

BROUGHT UP NEAR HANOVER

This Dartmouth graduate of the generation of Rufus Choate, John Wheelock, and Jonathan P. Cushing was a native of Vermont and spent the first years of his life only a short distance from Hanover. He was born in Woodstock, the son of Charles Marsh, a prominent Vermont lawyer of good Puritan lineage who for forty years served as a trustee of Dartmouth College.

At an early age George Perkins Marsh showed signs of the intense intellectual curiosity that was to characterize the remainder of his life. At seven he was disobeying his parents' advice against excessive reading and slipping under a table in an unfrequented hallway to read the Encyclopedia Britannica. When he was finally caught, the bad light had already ruined his eyes and he was not able to use them for reading until he was eleven. He continued his studies, however, by receiving oral Latin and Greek lessons from his brother and other members of the family.

After a meager few months preparatory education at Phillips Andover, he passed the Dartmouth entrance examinations and entered the class of 1820 at the age of fifteen! He quickly distinguished himself in all his studies and, upon his graduation, easily led his class. Modern languages were not at this time included within the College curriculum, but Marsh took up the study of French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese on his own initiative, and by the time he finished College could speak these languages fluently. The ability with which he learned foreign language was related by his friends to be amazing. It was said that a month was sufficient for him to learn to speak any language fluently. This unusual faculty was no doubt built up during Marsh's long periods of abstinence from reading, when his sense of hearing was made very sensitive by the oral lessons in Latin and Greek.

Although Marsh was well regarded by his classmates and made the average number of friends, his first interest were always his books. He took little interest in sports and other activities which he considered "trivial." Once, however, when he was asked in his later life to take a hand in a game of whist with some friends, he replied with a smile, "No, I believe not. I did too much of that in my college days, and I have never taken a card in my hand since."

Following his graduation from Dartmouth Marsh studied law in his father's office in Woodstock, and upon passing his bar examinations in 1825 moved to Burlington, the largest and most promising community in the state. Here he rapidly became one of the city's leading attorneys but at the same time he managed to continue his intellectual pursuits. Every morning between the hours of five and eight he spent in study. Having mastered the Romance tongues he commenced work on the languages of Northern Europe, and had soon become fluent in German and the Scandanavian tongues. His studies in these subjects marked Marsh as one of the foremost philologists of his day. His IcelandicGrammar was the first work on this language published in English.

In 1842 Marsh was elected as a representative to Congress, and he was re-elected in 1844 and 1846. In the National House he was a strong, although not an outstanding, figure. His speeches, scholarly and convincing, were confined primarily to the leading questions of the time. He was one of the first of the New Englanders to take an unwaivering Northern attitude upon the slavery question, and he opposed the annexation of Texas and the Mexican War, as he saw in both of these events the extension of slavery.

In the presidential election of 1844 he campaigned for Clay, and, upon seeing a flag hoisted in Washington for Presidentelect Polk on the morning following election day, remarked to a friend, "Do you know what that flag is waving over? There is the Slave Market of Washington! and that flag means Texas! and Texas means Civil War, before we are done with it."

MADE MINISTER TO TURKEY

Marsh was instrumental in 1848 in carrying his state for General Taylor, and as a reward for this service, and in recognition of his outstanding Congressional career, Taylor appointed him Minister to Turkey early in 1849. At this post Marsh served ably and distinguishedly until his recall four years later after a chance in the Administration at Washington. Although the American Minister's ranking was a lowly one at the Turkish court, Marsh soon became recognized both for his intellectual abilities and his handling of this country s interests abroad. His efforts on a specia mission in behalf of The Rev. Jonas King, well-known American missionary in Athens, freed the latter from religious persecution at the hands of the Greek authorities

While in the Near East Marsh took an extended trip into Egypt and through the Holy Land, where he made numerous scientific observations and collected various species of rare fish and animals for Smithsonian Institute at Washington. He did not meanwhile lose interest in his studies, but learned Turkish, Arabic, Persian, and modern Greek.

On his return to this country in 1854 Marsh moved back to Burlington to look after his business affairs, which had become complicated, but at the same time he took an active interest in politics and served on the Vermont Railroad Commission. He refused an offer of a professorship of history at Harvard, but during the winters of 1859-60 and 1860-61 delivered a series of lectures on the English Language to graduate students at Columbia University. These lectures were later published, and for years afterwards they of- fered to students of English original material and information of invaluable use.

When Lincoln became President in 1861 he named Marsh as the first Ameri can Minister to the new Italian Kingdom in which position Marsh served through four changes of administration until his death in 1882. Carl Shurz and William Cullen Bryant had also been considered for the post, but Marsh's notable services in Turkey and his rank among American scholars secured the position for him, and so courageous and distinguished was his tenure at the Italian court that none of the new incumbents at the White House would consider his removal.

Marsh attained a place of great prestige at the Italian capital and his diplomatic efforts were marked by almost unbroken success in drawing the governments of the United States and Italy into friendly and mutually advantageous relations. When the Civil War was being waged in this country Marsh was instrumental in keeping the Italians on the side of the Union cause. He negotiated several treaties and conventions between Italy and the United States, and at one time was a successful umpire in a Swiss-Italian boundry dispute.

It was during this latter period of his life that Marsh published the book upon which his chief literary fame rests TheEarth as Modified by Human. Action. This work is an interesting and scholarly analysis of the influence that man has exerted upon the forces of nature. Modem andMediaeval Saints and Miracles, another book written about the same time, is principally a defense of New England Puritanism and a criticism of Catholicism.

"Marsh's long and eventful career finally came to an end in 1882, when he quietly passed away at a little village near Florence, Italy, where he had gone to spend his summer vacation. His remains were taken back to Rome for the burial, where the homage of two nations was paid to his many years of distinguished service.

George Perkins Marsh, 1820

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH HALL—OLD AND NEW

January 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1936 By Prof. Narthaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

January 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1935

January 1936 By William W. Fitzhugh Jr. -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

January 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

January 1936 By F. William Andres

Milburn McCarty '35

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

February 1951 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, FRANCIS C. CHASE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

October 1951 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, FRANCIS C. CHASE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

January 1958 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, FRANCIS C. CHASE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

January 1960 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, FRANCIS C. CHASE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

January 1956 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, FRANCIS C. CHASE, THEODORE M. STEELE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

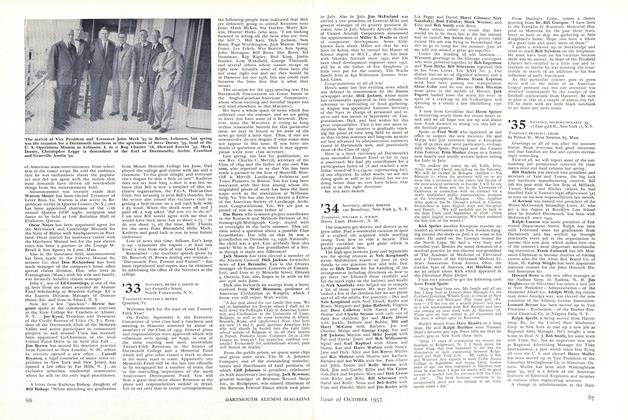

June 1957 By MILBURN MCCARTY '35, THEODORE H. HARBAUCH

Article

-

Article

ArticleCongratulations

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleCHRYSLER EXHIBITS MODERN ART

March 1941 -

Article

ArticleUpsurge in Applications

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Names on the Moon

MARCH 1971 By ALLEN L. KING -

Article

ArticlePennsylvania 13, Dartmouth 0

November 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleThe Student Days of Richard Hovey

February 1951 By EDWARD C. LATHEM '51