DARTMOUTH HALL, which is now nearing completion in its third apparently identical incarnation, had its genesis in the fertile and ambitious mind of Eleazar Wheelock. As early as July, 1770, a month before he moved to Hanover from Connecticut, he had written to the board of trust in England which had charge of funds raised there by Whitaker and Occom: "I propose to build withbricks, and 't is generally thought best that the firstbuilding be as large as two hundred feet long andfifty wide, and three stories high." Undaunted by the fact that his infant college was established in a virtual wilderness far from sources of materials for the erection of an elaborate edifice, he labored hard for the next four years on his scheme for such a hall. For the furtherance of this project the Provincial Assembly of New Hampshire on May 27, 1773, voted five hundred pounds to the Trustees of Dartmouth College "to assist in erecting a new college," and subscription papers were circulated in New York and New England in response to which between four and five thousand pounds were said undoubtedly with much exaggeration to have been pledged for the same purpose.

In July, 1773, Wheelock informed the English trust that a skilful architect had been employed to prepare a plan for a building of stone and brick 175 feet long, 52 feet wide, and three stories high above a "rustic" or ground story; it was to be finished "inthe most plain, decent, and cheapest manner, afterthe Doric order." In fact, two artists had been asked to submit plans: Peter Harrison of New Haven, the foremost architect in the Colonies at that time, designer of Redwood Library and the Brick Market in Newport, King's Chapel in Boston, Christ Church in Cambridge, and other notable buildings; and one William Gamble of lesser fame and ability. Harrison's plan, which was accepted, has disappeared perhaps it was sent to the English trust for their information and approval. Gamble's rejected plan and elevation are still in the possession of the College and show considerable resemblance to Dartmouth Hall as finally constructed in the following decade. It has been conjectured that the unknown designer of the latter building worked without definite reference to either Harrison's or Gamble's sketches but drew on his composite memory of both.

In the summer of 1774 Wheelock had a cellar excavated on his own land, near the site of the present Dartmouth Hall, and collected some bricks and stone. The state of public affairs, however, prevented the payment of the subscriptions pledged, the outbreak of the war in the following spring cut off all hope of aid from abroad, and Eleazar Wheelock died with his dream of a dignified college hall unfulfilled.

AFTER THE CLOSE of the war, the increase in number of students in the College and the dilapidated condition of the original buildings made imperative the provision of more adequate quarters both for living and for instruction, and Eleazar Wheelock's plan for an edifice modelled after Nassau Hall was revived and pushed to completion by his son John. In March, 1784, the Board of Trustees resolved, as soon as two thousand pounds should be subscribed, to erect, on the spot Dr. Wheelock had chosen, a brick building three or four stories in height and long enough for six rooms on each side, with ample hallways. Committees were chosen to solicit funds and make plans, and Professor Bezaleel Woodward was appointed to contract for labor and materials and superintend the work. The task proving too arduous for Professor Woodward, he was succeeded in September, when the work was just beginning, by Colonel Elisha Payne of Lebanon, a Trustee of the College, who with great diligence and much self-sacrifice saw the project through nearly to its completion in 1791, and then waited the rest of his life for full payment for his labors. The final settlement was made by the Trustees with "G. Kendrick, administrator of the estate of Colonel Payne," on July 8, 1808.

This much-delayed settlement indicates the extreme difficulties encountered by the Trustees in raising money for the project. By January, 1785, nearly three thousand pounds had been subscribed, but payment of the pledges was very slow and often failed altogether. The subscriptions were payable "in money, merchantable beef, pork, grain, boards,glass or nails," and the account book of Colonel Payne, to whom the later collections were turned over, shows receipt also of hides, tallow, rum, and even three pairs of men's shoes. The New Hampshire Legislature, on November 3, 1784, authorized the setting up and carrying on of a public lottery to raise money for the building, but the tickets sold very slowly, resulting in a complete failure to accumulate anything but debt. On Sept. 27, 1787, the Legislature authorized a renewal of the lottery, to raise eighteen hundred pounds, including expenses and redemption of the old tickets. After more than three years' delay, these second tickets were drawn in January, 1791, in of all places the desk of the College Chapel and yielded three hundred and sixty-six pounds. In addition, some of the College land was sold, and four hundred pounds was borrowed at ten percent interest. The final installments of the debt incurred were paid after the turn of the century from various funds of the College.

IN SPITE OF these difficulties the work of building progressed continuously, if slowly. The original plans were modified, substituting wood for brick and reducing the size of the structure to 150 feet in length, 50 feet in width, and three stories in height. A sum of ten pounds was borrowed of John Phillips on which to commence operations. The cellar was dug and a part of the stone foundation laid in 1784, and a new sawmill was erected on Mink Brook for preparing lumber. The first item of expense in the account of Colonel Payne reads: "Sept. 29,1784. To2 qts. Rum by Mr. Holden about digging cellarfor the new edifice." All the rest of the construction was also aided from time to time by liberal allowances of rum.

The massive pine timbers of which the frame was constructed were cut on the Etna Highlands, drawn by oxen to the mill of Colonel Payne at the outlet of Mascoma Lake in East Lebanon to be sawn; and thence, still by ox-team, to Hanover. These timbers were 15 inches square, 75 feet long for the longitudinal sills, and 50 feet long for the chords of the roof. John Sprague was engaged as the master carpenter. The frame, as was customary with all buildings of the time, was jointed on the ground and raised into position by the sheer power of men's muscles. The raising, under the direction of Colonel Joshua Hazen of Norwich, who was paid one hundred pounds for the job, took place in the summer of 1786. From the reminiscences of William W. Dewey we learn that "Ten days were occupied in setting up the frame. The workmen attendedprayers every morning and evening in theCollege Hall, which were offered up by Prof.Ripley and he was the first man that ascented theridgepole."

During the following year the building was boarded in, and although no partitions had been erected, the Commencement exercises of 1787 were held on Sept. 19 on the lower floor. I suppose in a way this may be called the dedication of the new building. A platform erected for the faculty and Trustees collapsed during the exercises, and although no one seems to have been injured, an ancient account tells us that "some of the reverendgentlemen had to look for themselves in one placeand for their wigs in another."

In the preceding July, Israel Parsons of Hatfield, Massachusetts, had been engaged by contract for one thousand pounds to complete the joiner work on the inside of the building, also the jut and outside finish and dial, and to finish the cupola "withproper ornaments agreeable to the rules of architecture." The Trustees agreed to furnish all materials and to board the workmen. As an aid to fulfilling this latter bargain, we find Colonel Payne paying seven pounds, six shillings, and sixpence "To hireof a Garden of Gilbard for Sauce for Workmen onthe College." The carpenters were paid four shilling ($.662/3) a day and their board; one who "found himself" received six shillings ($1.00).

THE CHIMNEYS were built in 1788, as appears from a letter of Colonel Payne to President Wheelock in which he complains of the difficulty of obtaining masons at a time when he has "the stones ready fortwo foundations and a bed of clay trod." Bricks were purchased from yards in Hanover and Lebanon; lime was brought from Lebanon, and from Cavendish and Saltash (now Plymouth), VermontNails were purchased in Grafton and Rowley, Massachusetts, while the door handles and other hardware were hammered out by hand in the blacksmith shop of Roger Hovey at Hanover Center.

In the fall of 1790 Parsons withdrew from the job, and Ebenezer Woodward was employed to furnish materials and complete the work. The Trustees had no cash to pay Parsons, but gave him a series of notes payable annually in wheat at four shillings and sixpence per bushel at the mill of Captain Phelps "at the White River Falls." In March, 1791, Colonel Payne resigned from the superintendency of the project, and Ebenezer Woodward was put in charge. The latter also agreed, in September of that year, to lath and plaster the whole interior, and for his pay he received from the Trustees ten acres of land on the College Plain, extending from the present site of Chandler Hall to a little north of where Webster Avenue runs, and westward to the river that is, approximately the tract we know as "the Hitchcock property."

The whole work was now quickly finished. The first room to be completed, says Dewey, was the northwest upper room, in the autumn, of 1791. Its first occupant was George Whitefield Kirkland of the class of 1792, the son of Eleazar Wheelock's early missionary, Reverend Samuel Kirkland. This very room acquired later and greater fame from the tradition probably inaccurate that it housed Daniel Webster during his senior year. Waters Clarke painted the building, inside and out, and Phineas Annis whose name therefore certainly deserves commemoration finished the graceful cupola, the most beautiful and distinctive architectural feature of the building. The exact cost of the entire work is not ascertainable, but Mr. Frederick Chase estimated it to be about forty-five hundred pounds, or fifteen thousand dollars. When allowance is made for the change in purchasing power, this means the equivalent today of approximately seventy-five thousand dollars.

For nearly forty years the building was known simply as "The College," the name of Dartmouth Hall not being bestowed upon it until 1828, when the erection of Thornton and Wentworth Halls made necessary a more distinctive appellation. Throughout this time, too, it served all the uses of the College save those of chapel and commons. The College library, opened one hour every two weeks, and furnished with about four thousand books "notselected because of their appropriateness for a college library," was housed at first in a room in the middle of the second story, but later moved to the first floor. Tradition says this change was made to Prevent the students from throwing the books downstairs! The room above the library was reserved for "the philosophical apparatus" which President Wheelock with so much fanfare had obtained from England, and another room near it was given over to the museum of "curiosities collected by formergraduates and others on their travels, the most noticeable of which was the stuffed skin of a largefowl understood to be found in South America." Another of the museum's treasures, dear to President Wheelock, was a stuffed zebra which the students loved to purloin and transport to the belfry or the stage of the College chapel. The Social Friends and the United Fraternity had two rooms reserved on the second floor for their libraries far more useful than the College library, and a rear room on the first floor was also set apart for the regular meetings of these two fraternities and of the Phi Beta Kappa Society. From 1799 to 1811 the Medical School occupied two rooms on the first floor of the building.

UNTIL 1824, WHEN the recitation rooms were taken over by the authorities and provided and equipped by them, recitations were held in students' rooms. Each of the four classes was required to support a room for recitation purposes and to furnish it with a table and a chair for the instructor, a double row of long, unpainted benches for the students, and a small blackboard. Until 1822, when stoves were first installed, all rooms were heated by open fireplaces; and the only lighting came from flaming pine knots and glimmering tallow candles.

The majority of the rooms, of course, served as dormitories for students. In the main they were bare and uncomfortable. Professor Alpheus Crosby of the class of 1837 teHs us that his first recitation in college was prepared at a table made by piling one trunk on another, and by light struck from flint and steel. And Judge Samuel Swift of the class of 1800 records how he arrived in Hanover as a freshman in the winter of 1796, a tad of only fourteen years, to be assigned to a large cold room on the lower floor "of the great wooden air castle in which most of thestudents had their rooms,' how vainly he tried to heat it with green pine wood, and how homesick he was for his father's comfortable house in Bennington! There were no toilet facilities save the College pump on the green, and that notorious long, low building on the site of Fayerweather Hall that was known to the rough-and-ready students of these early days as "the Little College," to the classically minded young gentlemen of the mid-nineteenth century as "the Temple of Cloacina," and to the youths of later years simply as "Number Ten."

EARLY IN ITS existence the hall escaped disaster by a narrow margin. On Sunday morning, March 6, 1798, while nearly the whole community was attending services in the College church, fire broke out in the northwest corner room on the second story, originating from the fireplace. Fortunately it was discovered before much headway had been made, and the alarm given. Judge Swift has left us an account of President Wheelock hurrying to the scene and calling to the students "to secure theGreat Fowl." He further tells us that "a vigorous application of snow subdued the fire, and the building and most of its contents were rescued." The damage was confined to the room in which the fire started and those directly above and below it. George Foote was engaged to make repairs, and from his contract we learn certain interesting details in regard to the appearance of the rooms at this time. Among other things Foote agreed "to replacewith good well-seasoned boards as before, whetherpanel work or plain or woodwork or plasteringthe room in the middle story to be wellpapered and painted with as good and handsomepaper as was on said room before said fire and suchas will agree with the paint, which is to be of thecolour it was before the wash board to bepainted with Spanish brown and also the outer sideof the door leading to the entry which is to be numbered as heretofore."

Then on June 13, 1802, a small tornado sweeping over the College Plain did much damage to Dartmouth Hall. Dewey says that "the wind struck uponthe south front roof, stripping all the boards andseveral very heavy timbers some forty-five feet inlength and from the eaves three-fifths of the way upto the ridgepole Some of these timbers werecarried over east of the building and plunged intothe ground so deep that it was very difficult to getthem out again The building was sowrecked that one of the frightened students in thethird loft started instantly to make his escape fromthe building, attempted to open his door but couldnot do it, and so with his bare head stove out one ofthe panels and ran bareheaded out on to the common and remained there until the storm ceased."

But as destructive agents, fire and tornado were little worse than the undergraduates of the early 1800's. In the frequent riotous encounters between the students and the villagers, which nearly all centered about "The College," stones and brickbats flew back and forth with calamitous results, and when disagreements arose as they often did between the students and the faculty, muskets were sometimes discharged through the windows of the tutors' rooms. Isaac Patterson of the class of 1812 related that "for some offense Prof. Shurtleff fastened the college boys out of Dartmouth Hall onemorning and in the evening the boys obtained anold cannon, loaded it heavily with powder, applieda slow match, and blew down the obstruction. I wasinside, and the building rocked like a wagon. Thestudents were assessed over 400 dollars for damagesto the college building and rules." And in the Autobiography of Amos Kendall, who was graduated in 1811, one finds a long account of the series of rows instigated by the students in protest against the villagers leaving their cows on the common all night, "which was a great nuisance." The culmination of this warfare came on the night of June 19, 1810, when some sixty students banded together and drove twenty cows from the common into the large unused cellar under Dartmouth Hall, and then blocked the entrance by rolling into it boulders obtained from a stone wall in the vicinity. After repulsing with brickbats two members of the faculty who attempted to interfere, the boys covered the boulder pile with earth and capped all with a stack of new mown hay from a neighboring field. Excitement lan high in the village next morning, and about eleven o'clock a group of armed cowowners advanced upon the campus. All the students retired within Dartmouth Hall and barricaded the doors. The faculty, fearing violence, then appeared on the scene and marched around the building and alternately commanded and requested that the doors be opened. The students replied that this would not be safe, whereupon Professor Hubbard procured an ax, knocked out the panels in one of the doors, crawled in, and opened up the building. Then the faculty took possession and told the villagers to come and dig their cattle out. All the students were fined twenty-five cents each to pay for damages to the cattle and the stone wall.

THE BUILDING survived the long troubles between the College and the University without suffering material injury. In the spring of 1817 the University authorities and their supporters took possession, seizing the library, museum, and bell, and forcing the College to conduct its exercises elsewhere, but the students of both institutions continued to room in the hall. Violence nearly resulted, however, eight months later when the University attempted by force to capture the libraries of the Socials and the Fraters and the two factions met in the corridor of the second floor armed with sticks of firewood; but serious consequences were averted by the discretionary retreat of the University group from the enraged College students, allowing the latter to remove their books in peace to safer quarters.

THE FIRST MAJOR changes in the structure were made in 1828. Financial stringency during the preceding period had prevented the Trustees from keeping the College buildings in repair, and these were now so dilapidated that attendance was diminishing, students preferring to enroll in institutions where the accommodations were better. So Wentworth and Thornton Halls were built from funds raised by special subscriptions, and Dartmouth Hall was thoroughly repaired and painted inside and out. Blinds were put on the front; the cornice, which had been left unfinished on the south and east sides in 1791, was completed; and a clock, the gift of a friend to whom the desirability of such a donation had been revealed in a dream, was installed in the front gable.

A large room was now constructed for a chapel, two stories in height and extending the entire width of the center section of the building. The stage and desk for the president were situated at the east end of this room, and the only entrance was a single door at the west end. Galleries extended along the sides of the room with the organ and choir over the entrance. Seniors were seated at the front, then juniors, then sophomores, and freshmen in the rear. This arrangement soon led to the development of the custom of "rushing the freshmen" at the close of each morning and evening chapel exercise, the upperclassmen pushing the neophytes violently through the narrow and congested doorway onto the stone steps and the ground beyond. A freshman in the class of 1855 had his leg broken in such a rush, and in 1858 the Trustees put a stop to the practice by moving the platform to the west end of the chapel with an entrance on either side of it. The seniors were now the first class to emerge, and no one dared rush them.

When Reed Hall was erected in 1840, the libraries, museum, and laboratory apparatus were moved to the new building, freeing a number of rooms in Dartmouth for dormitory purposes. But hard usage and lack of repairs were again making the old hall unattractive, and the number of unoccupied rooms in the building increased year by year. Since the sum of money lost by the failure to rent these rooms was assessed by the College prorata on the students rooming in the village, those so assessed felt they had a vested right to break the windows and otherwise deface the vacant rooms. Matters thus going from bad to worse, in 1848 the Trustees raised by subscription funds sufficient for another thorough renovation of the building. The dormitory rooms on the two upper floors were rendered so attractive that they became the most desirable locations on the campus, and the recitation rooms on the ground floor were entirely remodeled, each being connected with a "guard room," occupied by a student responsible for its care. The hall was reshingled for the first time, and the cupola, which had fallen into extreme decay, was taken down and entirely rebuilt, with some changes in its lines and structure.

DURING THE YEARS from 1828 to 1885, at which time Rollins Chapel was constructed, the Dartmouth Hall Chapel was the center of student life, and offered, unfortunately, an outlet for some of the lower manifestations of that life. The stories of pranks played in that old room are innumerable. The president never knew when he entered what sight would greet his eyes. One morning in the 1830's he found the chapel occupied by a flock of turkeys that had been driven in during the night. At another time an antique cradle was suspended from the ceiling, labeled in large letters and with broad humor as a gift from the undergraduates to a professor whose first-born child had arrived the night before. A corpse stolen from the dissecting room in the Medical School was once carefully placed beneath the freshman seats. The most celebrated of all these escapades occurred in the 1880's when a small donkey, tied beside the desk on the stage, elicited President Bartlett's famous repartee. He had started to ascend the platform before he caught sight of the intruder; he turned quickly toward the expectant audience, saying, "Excuse me,gentlemen, I did not know you were holding a classmeeting" and strode from the room. At a much earlier date, the students one night removed the Bible from the desk, thinking to cause annoyance and shorten the exercises, but they had not calculated on President Nathan Lord's resourcefulness. He gave no sign whatever of having noticed anything amiss, but when the time for scripture reading arrived, rose and very slowly repeated from memory the whole 176 verses of the 119th Psalm! There were, too, the less amusing habits of "greasing the freshman seats" smearing the pews with lard or oil or molasses; of "wooding up" with deafening clatter upon the entrance of a faculty member or student who had for any reason made himself temporarily unpopular; of placing printed "grinds," always scurrilous and often obscene, between the pages of the hymnbooks or scattering them broadcast in the pews; of tampering with the pipes of the organ so that when air was let into the instrument weird and discordant noises would issue forth.

Rowdyism did not depart from the Old Chapel with the building of Rollins, for the former room continued to be used for "senior rhetoricals," those exercises of public speaking and still more public disturbance, and for mass meetings and class meetings of all sorts. The last interclass row to take place there occurred in the spring of 1903 when the sophomores introduced the fire hose from Fayerweather Hall into one of the back windows of the Old Chapel in order to break up a freshman class meeting. Activities quickly moved to the area behind the building and were stopped only by the courageous charge of the registrar, Mr. Tibbetts. Memorabilia books of many '05 and 'O6 men will still reveal small pieces of the felt hat Mr. Tibbetts was wearing when he breasted that stream of water. It should not be forgotten, however, that this room was also the scene of dignified and honorable assemblies. The first "Dartmouth Night," for example, with its purpose "to capitalize the historyof the College," was held here on September 17, 1895. The last exercise of any kind held in the original Dartmouth Hall was an athletic mass meeting, the evening of Feb. 17, 1904, in the Old Chapel.

A BELL, FOR WHOSE raising the College provided two quarts of rum, was installed in the cupola before the building was completed, and was first run for the Commencement exercises of 1790. This bell had six successors in the next century, each one a little heavier and a little more costly than its predecessor. Parts of the last one, melted in the fire of 1904, still exist in the form of little bell-shaped paperweights and watch charms treasured by alumni fortunate enough to possess them. Throughout most of the century the ringing, from rising bell to curfew, was in charge of a junior, who was given free rent in the "bellman's room" on the third floor.

THE STUDENTS, of course, frequently tampered with the bell, stealing the tongue or tying up the rope or ringing it at unseasonable hours. Since the College was in session in earlier times throughout most of the summer, the night before the Fourth of July was usually made hideous by an all-night ringing of the bell. On July 3, 1861, the Faculty attempted to forestall this by padlocking the bellman's room and nailing up the approach to the belfry, but an ambitious sophomore climbed the lightning rod to the tower, and provided against surprise by attaching a rope, down which he could slide in haste. A group of the faculty, determined to catch the culprit, proceeded to the upper story of the hall. Professor Henry Fairbanks spied the rope dangling outside a window, and reaching out, cut it off just below the eaves. Meanwhile, the bell-ringer heard his enemies approaching, and promptly started his descent. He fell, of course, from the eaves to the ground, but miraculously escaped with nothing worse than two sprained ankles. The next day, although suffering great pain, he attended the centennial celebration of the town of Lebanon at which Professor Patterson delivered the chief oration, sat bravely in the front row of spectators, and took particular pains to shake hands with the professor at the conclusion of the exercises. His fortitude was rewarded; the faculty remained in ignorance of his identity until he revealed it himself twenty years after graduation.

Gradually in the later years of the Nineteenth Century many changes occurred in the use and service of the building. Lamps, which had superseded candles for lighting, were in turn replaced by gas and electricity; stoves gave way to furnaces and finally to heating from the central plant. Recitation rooms were extended to take up all of the first and second stories, leaving to be used for dormitory purposes only the rooms on the third floor known for half a century as "Bedbug Alley." This famous corridor was the scene of many a student disturbance and the cause of much worry to the faculty in the days when their duties as teachers embraced also those of campus police. Gentle Professor Noyes, ordinarily as mild of manner and speech as any man could possibly be, is reported to have said, after a fracas in which the students successfully eluded the faculty, "And there I was,walking up and down Bedbug Alley and saying tomyself, 'Damn! damn! damn!' "

Mr. H. B. Thayer '79, kindly sends me the following reminiscences: "The Dartmouth Hall of my day was the Dartmouth Hall of the last half of the last, century. Thetop floor was used for dormitory purposes and wasknown as 'Bedbug Alley.' I remember it had a longcorridor running from end to end of the buildingfrom which the bedrooms opened. There was nocentral heating, no central lighting, and no plumbing. At the back of the building, during the winter,could be seen a pile of wood and usually someyoung men earning a little extra money by sawingit into stove lengths and carrying it up to the bedrooms. In spite of all the labor of getting the woodup to a point where it could be fed into the stovesin the rooms, it wasn't unusual for some young manfeeling an urge to create a little excitement to starta good-sized 'chunk' rolling down stairs. I roomedin 'Bedbug Alley' sophomore and junior years. Sophomore year I roomed with Dan Rollins who was oneof the most active men in the class but not in studies.It was he who worked out the College yell. CollegeChapel was on the first floor and Dan Rollins wasthe organist. He endeared himself to the whole College by playing a voluntary which was a medley ofthe popular songs of the day up to the exact moment when someone gave him the tip that the President or Professor Sanborn was entering the chapelwhen the music would slow down and turn intosomething appropriate for the commencement ofservices."

ON THE MORNING of February 18, 1904, while the student body was attending prayers in Rollins Chapel, fire broke out in Dartmouth Hall. Dean Emerson, hearing the cry of alarm from without and ascertaining the cause, ran up the center aisle to the desk, and as President Tucker paused in the giving out of the hymn and held up his hand for attention, announced "Dartmouth Hall is on fire!" The chapel was emptied in an instant. Although the last student had left the rooms on the top floor of Dartmouth less than ten minutes before, smoke and flames were now pouring from the windows of the room just under the center gable and from the cornice above. The fire, which had originated presumably from defective wiring, spread with incredible rapidity. A few students who roomed in the building tried to save some of their belongings, but found it impossible to do so; one boy, who managed to get into his room, had to be rescued by a fire ladder extended to his window. The village fire company and the students together strove valiantly to subdue the flames, but nothing could stop the fierce burning of those century-old pine and oak timbers. It was a bitterly cold morning, with the thermometer at twenty degrees below zero, and the water thrown upon the building quickly turned to sheets of ice. In less than two hours from the time the fire was discovered, nothing remained of the old hall but a heap of smouldering ruins, the huge northwest chimney, and a charred portion of the south wall.

There had been times in its one hundred and twenty years of existence when, already old but not yet venerable, Dartmouth Hall had been sneered at and scorned, but the moment that it disappeared all Dartmouth men discovered how deep and abiding had been their real affection for it the last remaining physical link with the College of the Eighteenth Century. While the fire was still in prog- ress, President Tucker called a meeting of the Board of Trustees to consider plans for rebuilding, and at the same time Melvin O. Adams '71 sent out a call for a meeting of the alumni to determine means for raising funds, concluding his notice with words that have become famous in Dartmouth annals: "This is not an invitation; it is a summons." The disaster denoted a turning point in the history of the College; more than any other single event, it served to crystallize alumni sentiment, and the immediate and generous response in money given at this time marked the beginning of that never-failing support of their alma mater that has characterized the alumni body ever since.

IT WAS DETERMINED to rebuild the hall on practically the same lines, but of red brick painted white instead of wood. The new building was made somewhat ampler in dimensions, the windows were larger, and there were some refinements of architectural detail in the gable and the cupola, but it was essentially a reproduction of the original edifice. Mr. Charles A. Rich '75 was the architect, and he writes thus of his work:

"1 count the rebuilding of the old DartmouthHall my greatest joy, as the glorious old buildingwas burnt to the ground, only two little windowsremaining, and the present building with about sixfeet in height added and a remodelling of its interior somewhat, was the result of loving remembrance of its mass and details, which was studiedand redrawn from a little 4x5 photo, which,thrown up to 14" scale, became a gray, ghostlikemass, but was in very truth the dear old building!The credit therefore should still go to some fellowwho lived in and around 1800 A.D. and to whomI take off my hat!"

The cornerstone of the new hall was laid on October 26, 1904, by the sixth Earl of Dartmouth, great-great-grandson of the second Earl, for whom the College had been named. He, with his wife and daughter, had come from England to be present at this ceremony. The laying of the cornerstone was made the central feature of a great two-day celebration, attended by large numbers of the alumni and many distinguished guests.

The actual construction, which cost $101,700, occupied the space of two years, the new building being dedicated on February 17, 1906. The Trustees, faculty, alumni, and students, after special exercises in Rollins Chapel, marched to the west side of the campus and thence by a path cut through deep snow directly to the front of the new hall, singing, as they approached, the Dartmouth Commencement hymn Milton's paraphrase of the 136th Psalm. Once more the thermometer had dropped far below zero, to the disruption of the College band which led the procession and the amusement of the students who marched behind it. The music began loud and bravely, but one by one the brass instruments froze into muteness, until only the drums were functioning. The hymn was necessarily sung without accompaniment. Dr. Tucker spoke the words of dedication, and the undergraduates marched around the building, cheering lustily, before they entered its doors.

Outwardly, as has been stated, the hall seemed unchanged, but inside the arrangement was entirely new. All three floors were given over completely to recitation, lecture, and seminar rooms and faculty offices. In place of the old chapel, extending through two stories, the center section was occupied by a large lecture room; on the first floor only. The first exercise in this room was conducted by "Clothespins" Richardson, at ten o'clock on the morning of the dedication, and his lecture skilfully interwove as only he could do it the thread of Dartmouth history with the strands of American literature. The new hall housed the departments of Greek, Latin, English, German, French, Philosophy, Psychology, Art, and Archaeology, and furnished ample recitation rooms for all of them. As the years passed and the College grew, these departments overflowed into other buildings and several of them moved away entirely; some modifications were also made in the arrangement of rooms, but the general plan and use of the hall remained unchanged for thirty years.

AT 1:20 ON THE MORNING of April 25, 1935, Dart. mouth Hall was again discovered to be on fire. The blaze started in the basement of the north wing, from an undetermined cause, but spread through walls and shafts to all parts of the building in such a way that the entire structure was gutted and the cupola and roof were destroyed before the fire was put out. The Hanover volunteer fire company, aided by the Lebanon company, battled the flames for five hours before they were finally able to quench them.

At the May meeting of the Trustees it was voted once more to rebuild, this time using the existing brick walls, which had been undamaged by the fire, but constructing an entirely new and fireproof interior of steel and concrete. The plans were drawn by Mr. J. Fredrick Larson, College architect, and the construction, by W. H. Trumbull of Hanover, was begun immediately and has progressed rapidly

The changes in the exterior of the building have been held to a minimum. Small crickets have been put on the main roof, over the doorways, in the hope of eliminating the unsightly penthouses above the entrances that in past winters have been necessary as protections from falling snow and ice. The crickets on the front bear the figures of 1904 and 1935, while the front gable is adorned with 1784 |n large bronze numerals. Some minor refinements m the details of the cupola have been made, and an extra basement entrance has been built on the east side to provide an additional exit from the auditorium. The bell presented in 1904 by J. W. Pierce '05, which came through the recent fire unharmed, has been rehung and will be struck electrically in connection with the chime system in the Baker Library tower.

In the interior there are many changes. The unique feature of the old hall that was omitted in the reconstruction of 1904 was the two-story chapel. The new structure restores this in the form of a central auditorium of two stories, but dropped so that it occupies the basement and ground floor instead of the first two stories formerly taken up. This auditorium includes galleries that in their shape and in their supporting boxed columns reproduce the details of the old chapel. It contains remarkably comfortable seats for 765 persons and will undoubtedly prove more useful to the College than any lecture room previously existing. A moving picture booth has been installed, ready for use at such time as some friend of the College shall provide the necessary apparatus to fill it.

Other changes in the interior of the building have been designed to fit present-day conditions and requirements by providing a larger number of faculty offices more conveniently arranged, and a series of class rooms reduced in size and increased in number. In general, three class rooms at each end of the building replace the former two. On the first floor there are, beside the auditorium, six recitation rooms; on the second floor, ten recitation rooms, two small lecture rooms, one seminar room, and four offices for the department of Classics; on the third floor, four seminar rooms and thirty-three offices for the departments of Mathematics, German, and the Romance Languages. These offices are arranged in groups opening into large vestibules for departmental use. The stairways have been moved to the westerly ends of the corridors and have been made straight and wider, to facilitate traffic between classes.

The heating system is somewhat more elaborate than any heretofore used in the College buildings, and includes automatically controlled humidifkation. Public toilets for both men and women have been installed in the basement. All the modern buildings on the campus are of fireproof construction, but the new Dartmouth Hall carries this to a degree not reached before. Concrete floors, steel stairs, fireproof partitions, steel door trim, and a copper-covered gypsum roof make it almost the last word in safety construction. Even the cupola uses wood only as an exterior veneer. Furthermore, it is expected that the new hall will prove to be the quietest building in the Dartmouth plant. Improved partition material, rubber tile floors, and a wider use of acoustical plaster in the ceilings of class rooms and corridors have been designed for this end. The building is now nearly complete, and will be rededicated and opened for use at the beginning of the second semester.

FOR NEARLY A century and a half Dartmouth Hall has dominated the campus of Dartmouth College, and it still does. With Baker Library towering far above it, with comfortable, even luxurious, dormitories and efficient modern laboratories and recitation buildings stretching far and wide to house the complex activities of the present-day institution, this old hall remains the focal point of Dartmouth sentiment. To the men of Webster's generation it was the sole physical embodiment of the small College that they loved; to the present undergraduate its gleaming walls are yet the chief visible symbol of "Dartmouth Undying."

Legitimate Lottery One of the tickets sold for the purpose of raising funds for building Dart- mouth Hall. Receipts from the lottery were a great disappointment.

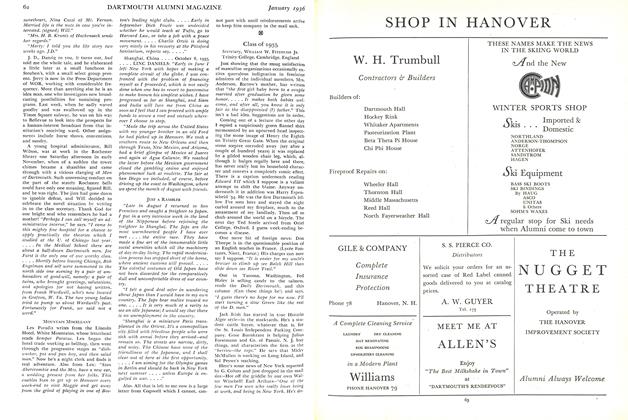

Plan for a College Building by William Gamble, About 2773 In his accompanying article Mr. Childs points out that the floor plans reproduced above are the only ones in existence although an alternative plan was drawn by another architect before the third drawing submitted was finally adopted as the model for the construction of the first Dartmouth Hall. Nevertheless, some features of the building were apparently taken from Mr. Gamble's plan.

The Famous Chapel of Old Dartmouth Hall, Reproduced in the New Dartmouth Hall

The Old Building Succumbed to Fire After More than a Century of Use Completely demolished less than two hours after this picture was taken on a bitter February morning in 1904,

Laying the Corner Stone, 1904 The Earl of Dartmouth accepts the trowel from Congressman Samuel L. Powers '74.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

January 1936 By Prof. Narthaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

January 1936 By Harold P. Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1935

January 1936 By William W. Fitzhugh Jr. -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

January 1936 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

January 1936 By F. William Andres -

Article

ArticleForgotten Dartmouth Men

January 1936 By Milburn McCarty '35

Francis Lane Childs '06

-

Books

BooksA FURTHER RANGE

October 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Article

ArticleMr. Tuck 75 Years After Graduation

June 1937 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksSTEEPLE BUSH

July 1947 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Article

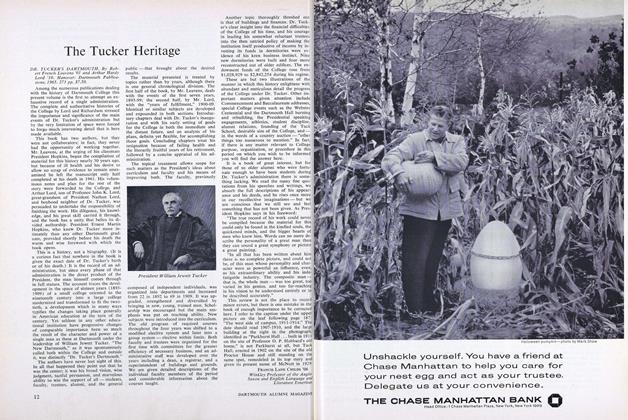

ArticleThe Tucker Heritage

OCTOBER 1965 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06