By Robert Frost '96. Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1936. 102 p. $2-50.

It is eight years since Robert Frost published his West-Running Brook, and that large number of us who regard him as America's foremost living poet hailed with delight the appearance this spring of AFurther Range. Like all his books, it is a slender volume, with its contents as carefully winnowed a:s ever, the sound, hard wheat of poetry.

A dedicatory note explains the choice of title: "To E. F. for what it may mean to her that beyond the White Mountains were the Green; beyond both were the Rockies, the Sierras, and, in thought, the Andes and the Himalayas—range beyond range even into the realm of government and religion." The individual poems fulfill the promise of the title, but many of them, wherever the ranging implications of their philosophies may lead, still have their starting-point in the life and background of a New England farm. Robert Frost still knows "what to make of a diminished thing." A white-tailed hornet seeking to capture flies, a woodchuck prudently providing his two-door burrow, a blue-ribbon pullet in her pen, an isolated, weatherworn barn "at the bottom of the fogs," a roadside stand before a poverty-stricken farmhouse, a bird singing in its sleep—so simple are the objects that start Frost's imagination on its ranging. But the keenness of his observation, the utter clarity and marvellous condensation of his expression, the perfect welding of his subject into its form, and the deep suggestiveness of his thought transform these homely bits of experience into genuine poetry. The emotional responses aroused in the reader are sincere and profound.

That peculiar sense of humor that is at once native to the back country of Vermont and New Hampshire and yet entirely individual with Robert Frost plays over much of the verse in this book. Side by side with this humor runs the poet's quiet melancholy, tempering joy with grief and human intercourse with loneliness; the nice balance of the two enhances the sense of reality and truth that these lyrics possess. Compare, for example, "Departmental" and "A Record Stride" with "A Leaf Treader" and "They Were Welcome to Their Belief."

Somewhat more explicitly than in his earlier volumes, Frost here reveals the philosophy of life that he has drawn from his imaginative meditations on the humbier phases of existence and at least hints of its application to "government and religion."

"Steal away and stay away.

Don't join too many gangs. Join few if any.Join the United States and join the family- But not much in between unless a college."

However, he is never, even in his negations, in any sense a dispenser of propaganda, and for that we should be profoundly thankful in these days when so many poets believe they are called to reveal not the truth of life, seen steadily and whole, but the specific teachings of sects and parties, cast into whatever distortion the present limelight throws them.

One cannot "review" Robert Frost's poems; he can only urge his reader to acquaint himself with them at first hand and to make them a treasured part of his literary heritage.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

October 1936 By The Editor -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

October 1936 By Paul C. Belknap -

Article

ArticlePresident Reviews Social Changes

October 1936 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1886

October 1936 By Henry W. Thurston -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

October 1936 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

October 1936 By Albert I. Dickerson

Francis Lane Childs '06

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH HALL—OLD AND NEW

January 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Article

ArticleMr. Tuck 75 Years After Graduation

June 1937 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksSTEEPLE BUSH

July 1947 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Article

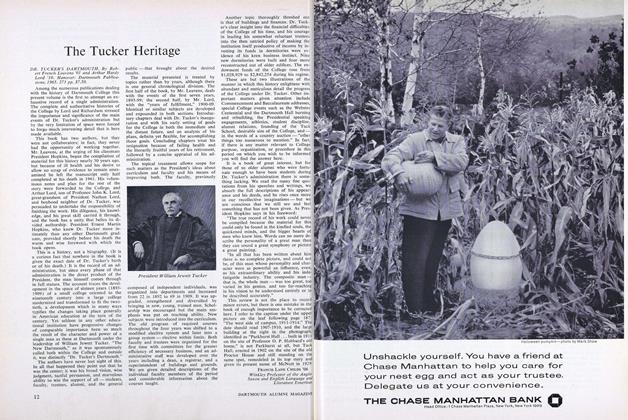

ArticleThe Tucker Heritage

OCTOBER 1965 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06

Books

-

Books

BooksFaculty Publications

MARCH 1929 -

Books

BooksShelflife

Mar/Apr 2006 -

Books

BooksAND HOW DO WE FEEL THIS MORNING?

JULY 1964 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Books

BooksTHE BONUS MARCH AND THE NEW DEAL,

April 1938 By Francis E. Merrill '26. -

Books

BooksPRIVATE.

DECEMBER 1970 By HENRY B. WILLIAMS -

Books

BooksNotes on a humanizing craft, a National Book Award, the Adamses, Avant-garde dancers, Irving Howe's tribute, and the Texas nation.

June 1976 By R.H.R.