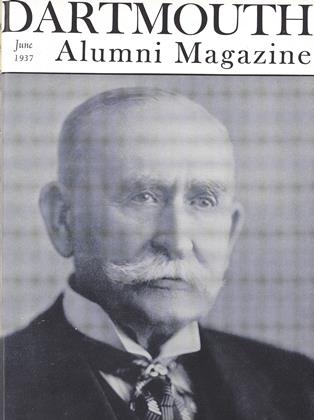

THE SENIOR GRADUATE OF THE COLLEGE IS DARTMOUTH'SGREATEST AND MOST THOUGHTFUL BENEFACTOR

IN THE LONG roster of Dartmouth graduates from 1771 to the present day fewer than ten names can be found of men who have had the good fortune to live to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversaries of their graduations. To that list will be added this month a name more distinguished than that of any of its predecessors—Edward Tuck of the class of 1862. Although the honor of being the oldest alumnus of the College is held by Dr. Zeeb Gilman '63, retently turned ninetysix, Mr. Tuck, who is over a year younger but a member of an earlier class, is Dartmouth's senior graduate, a fact which alone would justify this magazine in paying a diamond jubilee tribute to him. Length of years, however, is but incidental in our minds when we think of Edward Tuck, for it is as Dartmouth's greatest benefactor and most eminent living graduate that all Dartmouth men know him. No detailed biography will be attempted here, for that was excellently done in the MAGAZINE for June, 1932, but rather those factors in his life will be emphasized which illustrate so well the meaning of the justly celebrated Dartmouth spirit at its best.

Edward Tuck was born into and reared in the Dartmouth tradition. His father, Amos Tuck, was a graduate of the College in the class of 1835 and an able trustee from 1857 to 1866, who gave generously of his time and money in the interests of the institution. His home in Exeter was an ideal place for the development of a boy with a brilliant and sensitive mind, for here were constantly evident a reverence for knowledge, a love of literature and art, and a devotion to public service. Amos Tuck acquired a comfortable fortune by the successful practice of law, but he placed a far higher value upon things of the mind and spirit than upon money. He was an ardent leader in the antislavery movement, a member of Congress from New Hampshire for three terms on the Free Soil ticket, and one of the founders of the national Republican party—the reform political group of its day.

Phillips Exeter Academy thoroughly prepared the young Tuck for entrance to Dartmouth, and his college career was a credit to both institutions. Although he was graduated shortly before his twentieth birthday—there were but four men in his class younger than he—he ranked second scholastically and was of course elected to the Phi Beta Kappa Society. He was deservedly popular with his classmates, a member of the Psi Upsilon fraternity, and one of the best wrestlers in college. His only roommate, it should be noted in passing, was William Jewett Tucker '61. Mr. Tuck was chosen Class Orator, and the oration which he delivered on class day and which later appeared in print shows that whatever may have been the shortcomings of the curriculum of that period, at least it did develop in his case the ability to think clearly and independently and to express himself with clarity and vigor.

Four important formative years followed upon his graduation. Assiduous devotion to the study of law in preparation for a career intended to be like that of his father resulted in a threatened failure of eyesight that sent him to Europe for recuperation under the skilful administration of a renowned Swiss physician, and this chance shift of plans led to a complete redirection of his life. He was offered a clerkship in the American Consulate at Paris, soon to be followed by advancement to the post of vice-consul while still in his twenty-third year. For five months he served as acting consul. During his term of service he greatly widened his knowledge of world affairs and perfected his native gift for the tactful handling of human relationships. That at this early period he discharged the duties laid upon him with the thoroughness that has always characterized his actions is evidenced by the official praise bestowed upon him for the efficiency of his reports.

NATIVE TALENT FOR BUSINESS

Soon, however, he came to realize that the consular service offered no future that was attractive to him and he resigned his post to accept in 1866 a position with John Munroe and Company, at that time the sole American banking house in Paris. He was assigned to the New York office of the firm, where almost immediately he reivealed his natural bent for business. Business appealed to his imagination and stimulated the best qualities of his everactive mind. He threw himself heart and soul into the solution of the new problems confronting him; he studied long and hard to make himself a master of the intricacies of banking and currency. His diligence was rewarded in 1871 by a partnership in the firm, and he became known on two continents for his sound opinions and able administration in his chosen field. His many articles on financial subjects written for the journals of the day attracted wide attention. They showed in maturer form the same gifts for independent thinking and effective expression that were revealed by his class oration of 1862 and that are still evident in the tenth decade of his life. Within the last three years he has published in Scribner's Magazine two essays in support of bimetallism, "Honest Inflation" and "Stabilization by Specie Payments," that have been reprinted and widely read.

The guiding principles—one might almost call it the creed—of his business life are best expressed in his own words to President Tucker upon the establishment of the Tuck School. These words are inscribed on the walls of Tuck Hall and are familiar to most Dartmouth graduates, but they cannot be too often repeated:

"In the conduct of the school to which you have done my father's memory the honor of attaching his name, I trust that certain elementary but vital principles, on which he greatly dwelt in his advice to young men, whether entering upon a professional or business career, may not be lost sight of in the variety of technical subjects of which the regular curriculum is composed. Briefly, these principles or maxims are: absolute devotion to the career which one selects, and to the interests of one's superiors or employers; the desire and determination to do more rather than less than one's required duties; perfect accuracy and promptness in all undertakings, and absence from one's vocabulary of the word 'forget'; never to vary a hair's breadth from the truth nor frOm the path of strictest honesty and honor, with perfect confidence in the wisdom of doing right as the surest means of achieving success. To the maxim that honesty is the best policy should be added another: that altruism is the highest and best form of egoism as a principle of conduct to be followed by those who strive for success and happiness in public or business relations as well as in those of private life."

BUSINESS INTERESTS ENLARGED

In 1881, having acquired an independent fortune before he was forty years old, he retired from the firm of Munroe and Company, and for the forty-six years that have elapsed since then you will find his occupation listed as "retired banker." For him, however, retirement meant not a narrowing but an enlarging of his activities and interests. He freed himself from the confining routine of partnership in a large banking house, but he became an even greater power in the world of big business. His activities in connection with the Great Northern and Northern Pacific Railways, the Chase National Bank, and other important American business enterprises occupied a large part of his time and increased his property holdings rapidly. By 1900 he was a man of large wealth.

Like his father, however, he always regarded money as a means and not an end. On the granite monument in the Tuck burial plot in the Cemetery of St. Germain he has had engraved this quotation from Benjamin Franklin: "The years roll by and the last will come, when I would rather have it said 'He lived usefully' then 'He died rich.' " In the light of this sentiment he has lived; increasingly as the years have rolled by he has put his wealth to the useful service of his fellowmen. His benefactions, public and private, are astonishing in their number, their variety, and their amount.

MARRIAGE TO JULIA STELL

Mr. Tuck married in 1872 Miss Julia Stell, a noble-minded American woman then resident in Paris. For fifty-six years, until her death in 1928, their life together was one of unabated happiness. Their congeniality of tastes and purposes made possible a unique agreement not only in the benevolent disposal of their wealth, but in their quietly joyous way of lifeDuring the early years of their married life they made their home in New York, although they spent much of their time in Paris; in 1889 they became permanent residents of France, in Paris in the winter, and in summer at the Chateau de VertMont in the Commune of Rueil-Malmaison. Both homes became celebrated as centers of hospitality, where distinguished persons of many nations met on democratic ground.

Mr. Tuck has had a life-long interest in literature, art, and history, and he has devoted much time and money to the increase of cultural knowledge and appreciation. Over a long period of years he was a discriminating collector of objects of art and gathered in his Paris home a collection of great value and importance, which he donated in 1921 to the City of Paris and which is now housed in the Edward Tuck room in the Gallery of the Petit Palais. It includes tapestries, furniture, porcelains, enamels, paintings, and statuary, and is notable for the high' artistic quality of every piece included in it. He added to the Napoleonic museum at Malmaison, owned by the Government of France, the neighboring estate of Bois-Preau, once a part of the favorite domain of the Empress Josephine, and has purchased and given to the museum many valuable souvenirs of Napoleon and Josephine. Since his ninetieth year he has had restored at great expense the most interesting Roman monument in France. This is the Trophee des Alpes at La Turbie, erected B.C. 5 by the Emperor Augustus to commemorate the definitive victory of Rome over forty-four Alpine tribes which opened all Gaul to Roman civilization and began the history of France. A complete ruin when Mr. Tuck undertook its restoration, it required the greatest efforts of expert archaeologists and skilled engineers to reconstitute it in its original condition.

BENEVOLENT TO CHARITIES

This attention to aesthetic and historic matters has never overbalanced in Mr. Tuck's mind his humane interests. The suffering and the underprivileged have received largely of his bounty. For example, with the aid and advice of Mrs. Tuck he built and endowed at Rueil-Malmaison the Stell Hospital, accommodating sixty beds and equipped with the finest and most modern medical and surgical appliances. At the same place they established and supported a School of Domestic Economy, for the training of young girls. Both these institutions were organized and supervised by Mr. and Mrs. Tuck personally for twenty years until they were well established and had proved completely successful, when they were deeded to the Department of Seine-et-Oise. During the World War Stell Hospital was offered to the French Service de Sant6 and was accepted by the army as Military Hospital No. 66, but was entirely supported by Mr. Tuck. Throughout the war Mr. Tuck was a tower of strength in his relief and other charitable work, for Americans and Belgians as Well as for the French.

These are some of the many benefactions of Edward Tuck to the people of his adopted country, but although more than half his life has been spent in France, his ties of loyalty to America have never been weakened. His benevolences here have also been most numerous and varied. Particularly has he remembered his native state. The New Hampshire Historical Society building in Concord, by many considered the most beautiful public edifice in New Hampshire, was erected and endowed by him. The hospital, the nurses' home, and the academy in his native town of Exeter have received large gifts, and the neighboring town of Stratham owes its park to his generosity. The old church in Hampton in which his early ancestors worshipped was restored by him.

But the most unswerving loyalty of his life has been given to Dartmouth College. Separated from her by the space of an ocean and the distance of many years, he yet knows her better than do many of her next-door neighbors. Her physical appearance, her educational progress, her personalities, her actions and her atmosphere, her hopes and her fears—all are of intensest interest to him, and by maps and pictures and reading and correspondence he keeps pace with every change that comes to her.

Unquestionably Mr. Tuck would preserve a relatively intimate acquaintanceship with the affairs of the College under any circumstances. Nevertheless, it is probably true that his acquaintanceship with College affairs and College policies is accentuated beyond what it would be otherwise by the intimacy of relationship between him and several of the Board of Trustees and President Hopkins. The President's admiration and deep affection for Mr. Tuck have been too frequently expressed to alumni groups and to personal friends for any doubt to exist in regard to that. In turn, Mr. Tuck himself has expressed affection for the President as an intimate friend and has stated his admiration for him as a leader in the field of education. It has been possible for the President to visit Mr. Tuck occasionally through the twenty-one years of his administration and in these happy reunions the principal subject of mutual interest has been Dartmouth affairs.

And all Dartmouth men know him, though only a small number have seen him in the flesh, for the Dartmouth of to-day could not have been brought to her present state of efficient service as a liberal college without his generous aid.

FIRST DARTMOUTH ENDOWMENT

It was to Dartmouth in 1899 that Mr. Tuck's first large benefaction of any sort was made. Dr. Tucker's reconstruction and expansion of the College was well under way, but material support for his desired program was quite inadequate. Mr. Tuck, on his own initiative, perceiving with his usual keen insight into all practical problems the great educational value of the work being done by his old friend and one-time roommate, established in memory of his father an endowment fund for Dartmouth of $300,000, in securities that soon advanced to the value of $500,000. He expressed the desire that the income from this fund should be utilized "for the maintenance of the salaries of the President and the faculty at figures that will tend to secure and retain the services of professors of the highest ability and culture," a part for the increase of present salaries and a part for the establishment of additional professorships in the college proper or post-graduate departments, and "for the maintenance and increase of the college library." At Dr. Tucker's suggestion and with Mr. Tuck's heartiest approval a part of the income of the fund was used for the establishment in 1900 of the Amos Tuck School of Business Administration and Finance. For the furtherance of this plan Mr. Tuck added in the following year a gift of $125,000 for erecting, equipping, and maintaining a building for the use of the school.

Of this munificent endowment fund Dr. Tucker wrote in My Generation: "It was the most important individual factor in the reconstruction and expansion of the College. The amount of his benefactions, and equally their object gave security to the advances already made, and enabled the College in due time to take the initiative in a new field of academic training. They also gave direct moral support to the policy of the administration. Mr. Tuck was the first of the alumni of means to identify himself financially with what had begun to be known as the 'New Dartmouth'; and his aid preceded any organized or collective financial support on the part of the alumni. It was the more gratifying and assuring that it was altogether unsolicited, indeed unlooked for. Mr. Tuck had spent most of his time abroad since his graduation His interest in the College was not developed by contact with its activities or by reminders of its needs."

ADDITIONAL GIFTS TO THE COLLEGE

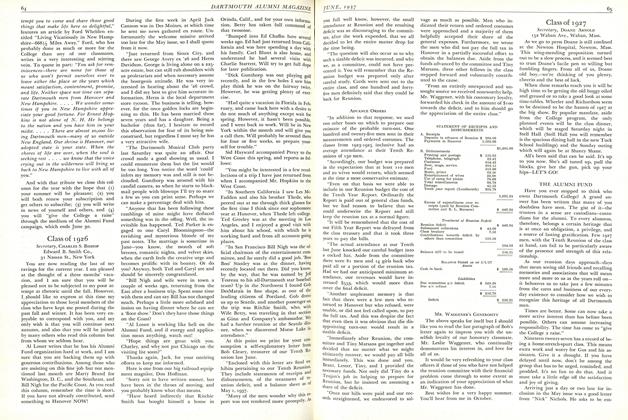

A detailed account of the long series of Mr. Tuck's later benefactions to the College is not needed here, for they are known to every reader of this MAGAZINE. At the beginning of President Nichols's administration he added another $500,000 to the endowment fund, for the increase of salaries; in 1913 he established a professorship of French and paid for the construction of Tuck Drive; he further increased the endowment fund from time to time; he paid for the reconstruction of Tuck (now McNutt) Hall in 1919, for the building of the President's House in 1925, and of the new* Tuck School group—Tuck, Chase, Woodbury, and Stell Halls—in 1938. In addition, he has made many smaller gifts and has aided in meeting deficits in trying times. All in all, the treasurer's books today carry the value of the Edward Tuck Endowment Fund at three and a half- million dollars, and show in addition gifts from him for construction purposes of nearly a million dollars.

The value to the College of these gifts cannot be measured in figures alone. The wise insight which Mr. Tuck has shown into the needs of the institution, the remarkable timeliness of all his donations which has made them of far greater worth than they would have been had they come at earlier or later dates, and the complete freedom from restrictions with which he has designated them have been of incalculable importance in the development of Dartmouth College. He has had faith in the new life of his alma mater and trust in her officers of administrations; consequently he has indicated the general purposes for which his gifts should be used, but he has left the details of their management to President Hopkins, the trustees and other officers of the College. Never has he sought to dictate or interfere.

GREAT HONORS AWARDED

Now at Malmaison he will soon complete the seventy-fifth year since his graduation. Great fame has come to him. He and Mrs. Tuck were the first foreigners ever to be awarded the Prix de Vertu of the French Academy; the names of both of them are inscribed on the great marble tablet in the Louvre as generous donors to the national museums of France. He has received the Grand' Croix de la Legion d'Honneur, the highest honor France can confer upon a private citizen; numerous medals have been awarded him, and in 1932 he was made Citoyen de Paris. But all this glory has left him untouched with conceit. His natural modesty is best illustrated by the statement he made to the Trustees of Dartmouth in 1923 when he asked that the name of the Amos Tuck Endowment Fund be changed to the Edward Tuck En- dowment Fund, in view of the fact that the School of Business Administration was named for his father. "I have no special vanity about it," he wrote, "but it seems to me that my own name had now better be connected with the Fund so that future generations may not ignore entirely my connection with it."

Edward Tuck is old only in years. He still preserves his fine physique, his vigorous mental powers, his humor and his humanness. His eyes twinkle, his wit sparkles," his kindly interest in all his friends is unabated. He loves his dogs, his flowers, his fine wines, the theatre and the opera. What finer example of the ideal Dartmouth man can be found through all the long course of Dartmouth's history? To Edward Tuck, seventy-five years out of college, go at this season heartiest greetings and good wishes from all the far-flung Dartmouth fellowship.

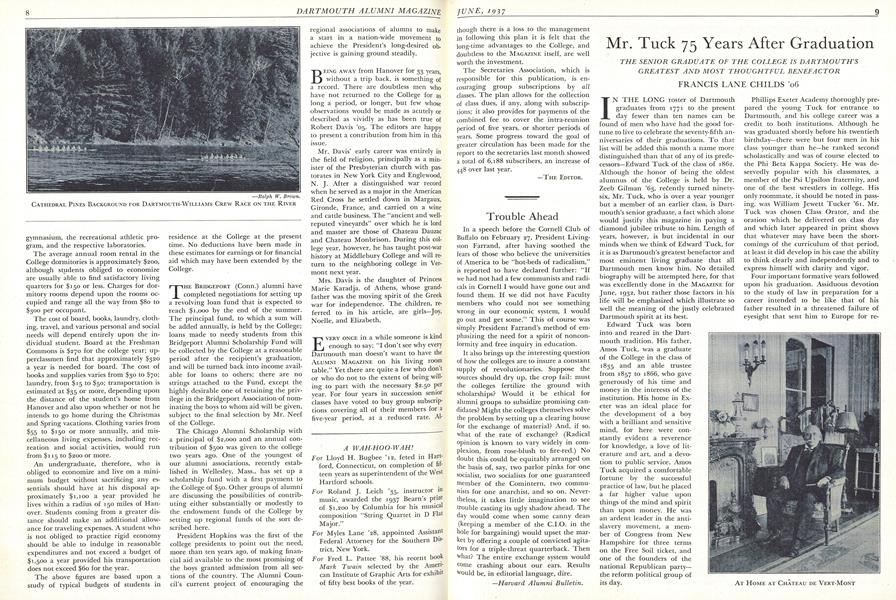

AT HOME AT CHATEAU DE VERT-MONT

BRONZE HAUT-RELIEF AT THE MAISON DES NATIONS AMERICAINES, PARIS

FOYER OF TUCK SCHOOL Showing the bust of Mr. Tuck by PaulLandowski

Stell Hall Chase House Tuck Hall Woodbury House THE AMOS TUCK SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION AND FINANCE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCollege of a Thousand Elms

June 1937 By PROFESSOR CHARLES J. LYON -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

June 1937 By Doane Arnold -

Article

ArticleHow Does the College Change?

June 1937 By ROBERT DAVIS '03 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1931

June 1937 By Edward D. Gruen -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

June 1937 By Richard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

June 1937 By Harold P. Hinman

FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH HALL—OLD AND NEW

January 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Books

BooksA FURTHER RANGE

October 1936 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Books

BooksSTEEPLE BUSH

July 1947 By Francis Lane Childs '06 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Article

ArticleThe Tucker Heritage

OCTOBER 1965 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Books

BooksAUBURN, NEW HAMPSHIRE 1719-1969.

APRIL 1971 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06

Article

-

Article

ArticleBOSTON UNIVERSITY CLUB PLANS LECTURE SERIES

FEBRUARY, 1927 -

Article

ArticleA Wah Hoo Wah!

July 1953 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

Nov/Dec 2006 -

Article

ArticleSoccer

NOVEMBER 1967 By ALBERT C. JONES '66 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

January 1948 By JOHN P. STEARNS '49. -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT 1923

August, 1923 By WILLIAM H. MCCARTER, 1919