A VACATIONING SON OF THE COLLEGE RETURNS WHEREONCE HE WAS "YOUNG, FOOLISH, AND BRAVE"

WE RUMBLED north, my typewriter and I, in the belly of "Phyllis," a roomy chair car of the New Haven road. Out of New York we sped in fury, making way for the city's commerce. New England received us with quiet grace. We slowed our pace. There was no hurry. We were away for a four weeks' holiday in Hanover. We sought sleep that would slow the pitch of the tuning fork we had become. We hoped to work, somewhat, with profit.

But they won't let you work in Hanover, not if you're an alumnus with a vacationing look. The village, in its wisdom, conspires against it. The College, recalling your efforts as an undergraduate, frowns upon it. And the air that comes full and heavy across Hanover Plain from the notches to the north forbids it. What can you do? You succumb.

First off, you clamber out of Dave Kaplan's dog-eared bus with its misleading motto, "Dartmouth Tours," and get set up in a room at the Inn. Then, on sneakerect feet, you wander, spotting new buildings, popping under archways, turning up walks and feeling ancient. Recalling football practice, you meander to the stadium and stand and stare at the meaty progeny of your once muscled self. The quick cry of joy you let loose as a swift halfback knifes a tackle dissolves into a wince as an end slaps him down. Suddenly the sun goes out and you're hungry. Hungry? You're weak!

It's the air. In October you can almost taste it. Filtered through mile upon mile of clean cloud and sunshine, pine and rock, it streams like tanked oxygen into your lungs that have pumped so long the bastard air of the city. And it sends you early to bed that first night. But you don't sleep. You die twelve hours nightly. Awakening the first morning, you're certain you've been drugged. In a few days you're fit to grapple with a baffling maze of problems that confront the pursuit of what has become your hand-made vacation in Hanover.

First, there's sitting, an art you have grown unfamiliar with. Sitting, you find, takes talent. It is best done on the verandah of the Inn, where, if you are quiet and unobtrusive, all of Hanover will sometime parade before you in procession across the plain. At mid-morning "Red," the bell captain, confronts you, in the neat, black type of your favorite newspaper, with the problems of your city. They seem trifling and distant. Mentally conjuring up from the headlines the downward swish of the franc as the French go off gold, you figure what you might have made if "God, she's beautiful!"

You look up, startled, for a thing of beauty. Instead you find two freshmen, green skull caps akimbo on their puzzled heads, who have settled down beside you. Without laughter they ponder love and studies. You eavesdrop, unashamedly. One longs for his girl, a modern "Helen," in Hartford. From hearing his account, you agree with him: She is beautiful. The other, unencumbered with love, is more practical. He, six weeks an undergraduate, is flunking two subjects. He is frightened. Their talk runs on in the channel of worries that beset you long ago. At last, in the sepulchral timbre of a Moslem prophet, the unloved one concludes, rising:

"I guess you know quite a lot when you get out of here."

You retreat gleefully behind your news paper as they depart. Your day is made. Let those minor prophets of doom with their wagging oral surfaces worry about the youth of America. It's doing all right.

In search of a book we strode boldly to the library and bravely entered. That, we found, was a mistake. You now have to select with caution your entrances into that comfortable structure of racked wisdom. We caromed in the nearest door at hand and ran smack into the Orozco murals. And every last one of those horrendous figures, even to the infant emerging new-born from a pile of books, arose to point an accusing finger at us. Palsied, we scurried out, dragging our sins behind us. In the sanctuary of Sanborn House we came upon a wayward volume, long ago left unread in deference to a "peerade" to Cambridge, and settled down to read it. Late that night the janitor awoke us and ordered us out.

You who have not renewed your ac quaintance with the janitors of Hanover have neglected an order of philosophers of astonishing versatility. Their observations, burned deep and strong by the winters they have worried through, are a challenge, to any man of affairs. We cornered one coming out for air, and lead with the weather.

"October's the month," he grudged, looking us over with heavy irony. "More sunny days than any other month; except maybe September. Weather Bureau shows it."

"How are you voting in the national election next week?" we went on, mentally sharpening the barbs of our best political arguments.

"Not voting. Don't like the candidates. No one to fight about like old Cal."

That floored us. Before we could go on, he sighted along his pipe-stem at the hills of Vermont and observed:

"Lookit those hills—all decked out like a peacock on a bender. Some like the summer. But New Hampshire ain't ripe till the pumpkins turn."

Down the Valley of the Connecticut the woodcock were winging southward. Shooting! That was it. Buster Brown, that handiest of men, will desert his labors at the click of a trigger to take you out for birds. Or, if you feel like trying out the most subtle dodges of your city salesmanship, you may succeed in persuading Dr. Howard Kingsford, Hanover's first sportsman, to reveal to you the secret places of his coveys of partridge, pheasant, and woodcock. In this you will be likely to fail. From his jealous colleagues, who often return with no birds, the doctor has long kept hidden his knowledge of the coveys in the thick cover about Hanover.

The time comes when you rent a car and journey away from Hanover through the notches. You cruise through little hamlets, resting unruffled at lonely crossroads. You stop at small county fairs and hear the talk of the people. A roadside auction pulls you like a magnet, and you hypnotize to the tommy-gun talk of the New England auctioneer, unconsciously bowing at his concluding: "Thank ya, kind friend, thank ya."

And how you eat! You curse your undergraduate ignorance in never having known the New England dishes that come hot and suave from these little inns. Boiled ham dripping with brown-sugared raisin sauce, the spiced aroma of Brown Betty, rich with the meat of the apple; maple sugar cookies and Bishop's bread, blueberry muffins and mincemeat pie. At the Hop Vine Tea Room in South Royalton, Vt., yoti discover in a corner the ancient earthenware crock with its buckwheat batter. The cakes come crisp from the griddle along with the trout you may have won from the stream, if you cast a dexterous fly.

You come back to Hanover, fat and contented and happy, ready for the week-end football game. You worry a pack up Mt. Moosilauke and feel again in your throat the rasp of physical effort. You pull a meditative pipe with professors who taught you. You drink hard cider and walk long walks in cold rain slanting down out of a gray, bitten sky. In time you feel fit and cool as butter. And then your holiday is ended.

That night we departed to catch the sleeper for New York City a steel engraving of a moon sat full upon the tip of the pine tree atop the library tower. Awaiting our bus, we wandered out across the campus to the undergraduates gathered at a bonfire for the morrow's game. We loaned our untuned voice to the words of the "Winter Song," intoning: "For the wolfwind is wailing at the doorways." We went away with a soft wind from the south. It had been deep and fulsome, holidaying in a land wherein you had once been very young and foolish and brave.

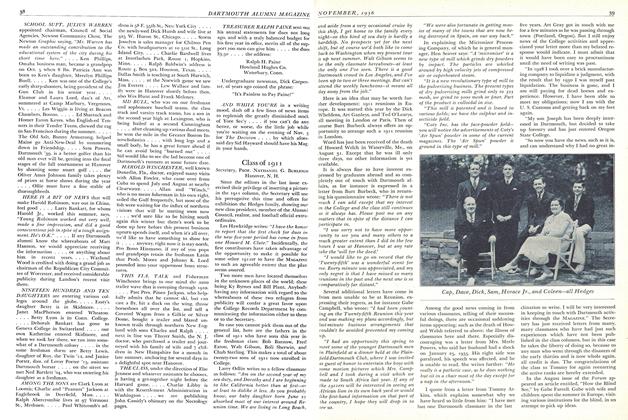

Mascoma Lake, in Nearby Enfield

Riding in Norwich

Hiking and Climbing

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleEat the Cake and Have It Too

November 1936 By WILLIAM J. MINSCH '07 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

November 1936 By G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

November 1936 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1918

November 1936 By Allan C. Gottschaldt -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1921

November 1936 By Paul C. Belknap -

Sports

SportsFollowing the Big Green Teams

November 1936 By ROBERT P. FULLER '37

Article

-

Article

ArticleTRACK ATHLETICS

JUNE, 1908 -

Article

ArticleCOMMENCEMENT AN INSPIRING SIGHT

August, 1922 -

Article

ArticleSpringfield Boys Organize

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleOff the record

JUNE/JULY 1984 -

Article

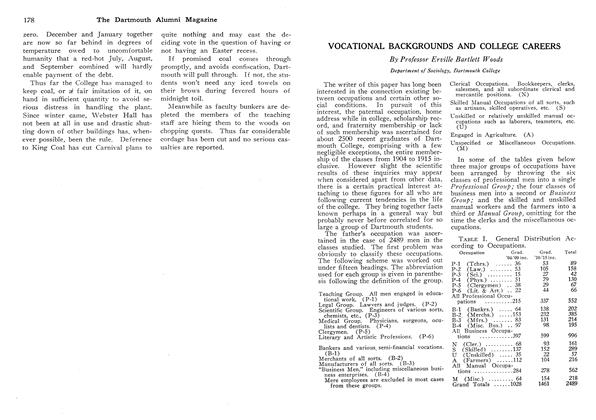

ArticleVOCATIONAL BACKGROUNDS AND COLLEGE CAREERS

February 1918 By Erville Bartlett Woods -

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

June 1931 By W. H. Ferry '32