Room 404 Gilman Hall is a wild clutter of a place, presided over by a tall, sprightly fellow named Gilbert who lopes unerringly around it in tennis shoes. He’s a rotifer investigator. He watches rotifers. “People have spent a lot of time classifying them before,” says biologist John Gilbert, “but very few have sat down and really watched them.”

Of course, he doesn’t just watch them. A doctorate from Yale and professorships at Princeton and Dartmouth don’t come to people who just sit around all day mooning over rotifers. Gilbert also cultures them, measures them, starves them, grinds them up with dissecting needles, feeds them to each other, and tampers with their sex lives (such sex lives as they have). He washes them, freezes them, filters them, sections their testes with glass knives, photographs the organelles in their guts, and analyzes the chemistry of their embryos. And he writes about them, under titles such as “Sex-Specific Cannibalism in the Rotifer Asplanchna sieboldi” and “The Adaptive Significance of Polymorphism in the Rotifer Asplanchna: Humps in Males and Females.”

“Affable and knowledgeable” the stu- dent Course Guide calls Gilbert, whose teaching specialty is invertebrate biology.

His credentials attest to his knowledge- ability, and his affability is immedi- ately apparent. He has the bounding energy and bright enthusiasm of a teen- ager, despite his graying hair and his 40 years. He obviously has a lot of fun doing what he does.

Gilbert’s laboratory is crammed with apparatus and covered with pictures. Some of the pictures are professional there are some stunning electron microscope photo- graphs of rotifer resting eggs (which look like the cratered moon) but most of the pictures are drawings by Gilbert’s children, Johnny and Anne. A cheerful red-and- yellow sunflower sprouts beneath the Erlenmeyer flasks, and three floppy-eared rabbits cavort behind the bubbling dis- tiller. A pink fmgerpaint ostrich watches over the pipette racks, and a cabinet door sports crayon poetry; Johnny is my brotherJohn is my fatherCally is my motherI have no sister but I have enouphTrubl without one.

Johnny also carved a sign for the refrig- erator. It reads, “Beware of the Rotifer!”

That’s a joke, of course. Rotifers are harmless little water bugs, microscopic and transparent, first described in the 19th century. Because their heads appeared to whirl in circles, early observers called them “wheel animalcules,” and they were thought to be single-celled. Later in- vestigators found that the whirling is only a visual effect created by the constant lashing motion of the many cilia, or hairs, that crown most rotifers. And they are not single-celled at all: rotifers turn out to be the smallest known multicellular orga- nism. (Mean rotifer length is about 200 txm, or .008 inch.)

Rotifers come in an astonishing variety of forms, but all are symmetrical and have a head, a trunk, and usually a foot. The great majority live in fresh waters of moderate temperatures weedy ponds, boggy pools, lakes, and canals. They move and feed by lashing the cilia that grow thickly on the skin around their mouth parts. Some are pear-shaped, others look like minute horseshoe crabs, and still others like grocery sacks. Their fuzzy heads give them all an unkempt, clownish look. The average lifespan of a rotifer is a matter of days, and some are considered old at eight hours. They have wonderful names, such as Notommata cerberus and Cyrtonia tuba. Gilbert works principally with Asplanchna sieboldi, a small, nor- mally sack-shaped, hunting rotifer.

A couple of drops of water from a local pond contain whole populations of the drifting microscopic plants and animals which constitute plankton and often in- clude rotifers. The microscope reveals a crowded world of tiny organisms, some floating placidly, others careering around in frenzied activity. It takes a minute to get used to looking down the dark barrels of the microscope, and another minute for the lighted circle at the bottom to resolve into something more than a jittery red- brown puddle. But finally the little transparent plankters appear. A chain of dark-edged lemon shapes floats calmly across the circle, and then a torpedo- shaped copepod with snapping antennae and whipping paddles darts across. It darts back, and there is time to notice the brilliant green threads and vivid red spots of its internal organs. A little barrel- shaped creature with a spiny head putts by, trailing a tiny sphere off its lower end by a thread. It is a rotifer, a Brachionuscalyciflorus, carrying its egg around.

A much larger, bell-shaped animal swims by, clapper first, its crown of ciliated mouth parts pulsating rapidly. It also is a rotifer, one of the giant Asplanchna, and if it happens to bump into the smaller rotifer and manages to capture it with its mouth, it will eat it, throwing its mouth outward with a violent jerk. On the return jerk, the prey will be drawn down into the jaws and the gullet and finally into the cellular stomach, which looks like a cluster of grapes. The small rotifer will struggle, and there will be a great frenzy at the working end of the giant, and then the small rotifer will lie still, plainly visible, in- side the giant.

Asked if rotifers ever become pets for him, Gilbert considers the question as if such a possibility has never crossed his mind before. Finally, he says, “No. They’re much too small.” He has no qualms, apparently, about all the dreadful things he does to rotifers in order to learn about them. Perhaps, as Peter Starkweather, one of Gilbert’s associates, says, rotifers don’t live long enough to make emotional involvement possible. “You get emotionally involved with what they tell you about themselves,” he ex- plains, “not with the rotifers themselves.”

The most far-reaching of Gilbert’s work with rotifers has to do with the effects of a- tocopherol (vitamin E) on Asplanchnasieboldi. Gilbert isolated a-tocopherol as the inducer of two fascinating phenomena in this rotifer: polymorphism and sex- uality. Normally, the sack-shaped Asplanchna are female, and they reproduce themselves by themselves, asex- ually, or by parthenogenesis. They give birth to female young which are. born alive and reproduce their mothers exactly. If they are fed sufficient amounts of vitamin E, however, they will give birth to rotifers some of which are not like themselves, but are cruciform that is, they have four big humps instead of being rounded and sack- like. They will also produce daughters capable of producing male as well as female offspring. These males may then fertilize some of the male-producing females and cause them to lay eggs, thick- walled, resistant eggs which fall to the bot- tom of the pond and winter over, sometimes for as many as 20 years. These “resting eggs” hatch out into normal, parthenogenic females, to start the rotifer routine all over again. Gilbert estimates that the occasional, or “facultative” sex- uality is an adaptive feature which allows the rotifers to utilize good times in order to get the species through hard times later.

This work has appealed particularly to the medical world, which is currently in- terested in vitamin E because it has been linked to human male fertility. Because the reactions of Asplanchna sieboldi to vitamin E are so definite and predictable, it is possible to use them to assay for the vitamin. One simply feeds the substance in question to the rotifers and then watches for humps and males. “Chemical assay,” says Gilbert, “is by several orders of magnitude less precise than this method.”

About four years ago, experiments with rotifers in the laboratory became tedious, however, so Gilbert switched to fresh- water sponges, which, as it happens, can- not be cultured in the laboratory. “That means field work,” he explains happily. “The graduate students and I drive out to Mud Pond in Canaan-Enfield, where we have set out some rafts, and we collect specimens and check the growth of our ;ponges. Then we fish a little and poke around until it’s time to go to the Riverside Grill for lunch.” He is a great believer in the Riverside Grill.

Gilbert’s sponge work also took him to Yugoslavia on a Smithsonian-sponsored project on the limnology (freshwater studies) of Lake Ohrid, one of the three oldest lakes on earth. An astonishing 950 feet deep at some points, Ohrid in its 200,000 years has produced over 300 species of flora and fauna unique in the world one of which is a yellow sponge studied by Gilbert.

Such work as this at Ohrid, in the vanguard of studies in his field, pegs Gilbert as a young scientist going places rapidly. He has already been very successful in securing grant moneys from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation for his rotifer work, an achievement he attributes to the popular concern with the effects of vitamin E on humans. In a less popularized and less “utilitarian” way, his most recent grant award is the result of his total scien- tific achievement and of his promise as a researcher. In 1973 he was given one of the coveted Career Development Awards from the National Institutes'of Health. It pays his salary for five years and releases him from all but one course of teaching in order to encourage his research.

The work in Yugoslavia is coming to an end now, and Gilbert intends to get back to rotifers. He plans to investigate the part they play in the food web of freshwater bodies, suspecting that they are much more important in ponds and lakes, both as prey and as predators, than anyone has heretofore imagined. He has found a way to do field work with rotifers. “I’m really looking forward to getting my hands wet with some rotifer predators,” he says happily.

Humped rotifer is child of vitamin E: cruci-form female of Asplanchna sieboldi, withhumps retracted (left) and extended (right).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Story: His Grandmother and Vincent

December | January 1977 By Howard Webber -

Feature

FeatureThe Well-Tempered Synclavier

December | January 1977 By Woody Rothe -

Feature

FeatureReflections on an $8-million post office The Hopkins Revolution

December | January 1977 By Henry B. Williams -

Class Notes

Class Notes1971

December | January 1977 By THOMAS G. JACKSON -

Sports

SportsThe Coach Departs

December | January 1977 By Brad Hills ’65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1974

December | January 1977 By STEPHEN D. SEVERSON

S.G.

-

Article

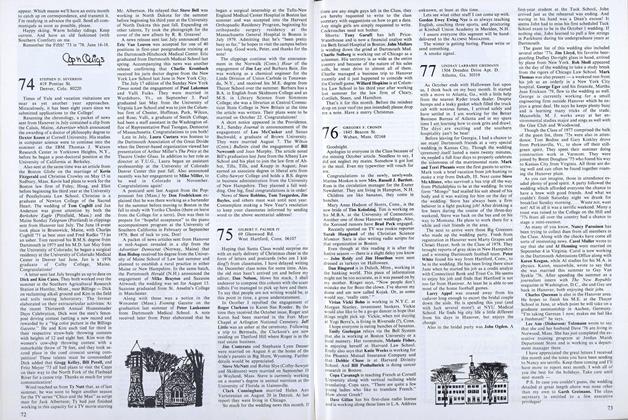

ArticleA Versatile, Admirable Teacher With "Every Feature of a Drill Sergeant'(sic)

March 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleA Red Letter Day

April 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleThe Call Heard Round the World

OCT. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleDick's House Is Her House

NOV. 1977 By S.G. -

Article

ArticleOf God, Man, and Mountains

JAN./FEB. 1978 By S.G. -

Feature

FeatureHomely Truths

JUNE 1983 By S.G.

Article

-

Article

ArticleFootball Banquet

January, 1911 -

Article

ArticleThe Versatile Professor of Chemistry Known to the Dartmouth World as "Cheerless" or "L. B."

January 1936 -

Article

ArticleThe second annual award of 1949's Gold

JANUARY 1963 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

MARCH 1983 -

Article

ArticleDOING SOMETHING ABOUT IT

December 1940 By Charles E. Dell '42 -

Article

ArticleSNOW ARTISTS

March 1936 By W. J. Minsch Jr. '36