SOMEBODY ASKS YOU: "What is all this about Dartmouth and the Dartmouth spirit? What makes it so different from any other college—or is it really different?"

You can't answer questions like that with one simple declarative sentence. Recollections after fifteen or twenty years are perverse things. Your mind rambles on through a series of disconnected pictures: President Hopkins behind the pulpit in chapel, starting the day right for you with his quiet example of sincerity, modesty and true scholarship: marching out of chapel as a senior, with all the other classes standing at attention; coming out to find the early morning sunlight speckling Dartmouth Hall with dancing patches of shadow. Classes that were boisterous; others, solemn with the power of knowledge; still others where learning seemed a friendly thing, permeated with the warmth of a guiding spirit. Files of undergraduates criss-crossing eternally back and forth over the diagonal paths of the campus. Over those paths you plodded to treacherous hour-exams, returned from memorable victories behind the gym, made new friends between one class and the next—and kept them with the passing of the years.

For* you the College must always be exactly as you left it. Go back again and again, and still you are only dimly aware of the changes that have come over the place. Much as an undergraduate grows from awkwardness to maturity, the architectural surroundings of the campus have developed almost imperceptibly from a hodge-podge to symmetry and dignity. The spire of the Baker Library beckons you on, as you cross the flats only half way up from the Junk. Its Tower Room and its murals will linger twenty years hence in the minds of today's undergraduates.

And yet there is an unreal quality about this bewildering array of brick and stone. The old church, your inner eye tells you, still guards its corner of the campus. Behind it looms the hideous yellow bulk of Butterfield. Diagonally across and down under the hill, there still must be the crazy, flat-topped Alpha Delt house. And surely, at the foot of Wheelock Street, the Ledyard Bridge reeks as ever to high heaven.

You can't make any particular sense out of all this, or draw a conclusion that will impress a logical human being. Pictures out of an old Aegis won't do it, and even Louis Orr's etchings may mean no more than expert craftsmanship to impartial eyes. Perhaps the simplest answer—if an answer must be had—is found in that brief paragraph which serves as a foreword to Mary Ellen Chase's story of Mary Peters. Strangely enough, it is from the Russian of Dostoievsky:

"You must know that there is nothing higher and stronger and more wholesome and good for life than some good memory, especially a memory of childhood If a man carries many such memories with him into life, he is safe to the end of his days, and if one has only one good memory left in one's heart, even that may some time be the means of saving us."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSOCIAL SURVEY REPORT

June 1936 By The Editors -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1935

June 1936 By William W. Fitzhugh Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

June 1936 By F. William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

June 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleTHE SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF '79

June 1936 By Clifford Hayes Smith -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

June 1936 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr.

R. M. Pearson '20

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

October 1934 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

March 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

April1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

May 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

November 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

February 1936 By R. M. Pearson '20

Article

-

Article

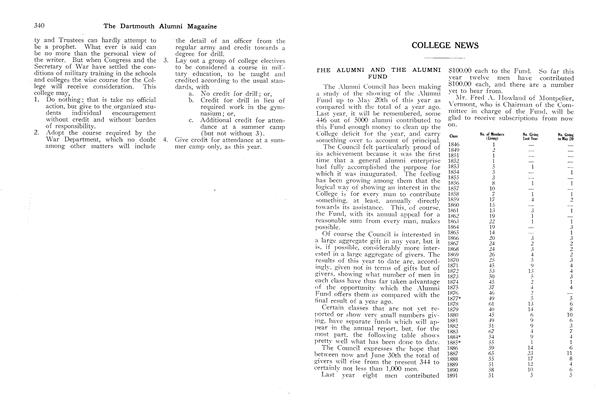

ArticleTHE ALUMNI AND THE ALUMNI FUND

June 1916 -

Article

ArticleFraternity Scholarship

AUGUST, 1927 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Speaking Tours

APRIL 1973 -

Article

ArticleOn the Waterfront

Sept/Oct 2005 By Ed Gray '67 -

Article

ArticleA Compressed Life

February 1993 By John G. Kemeny -

Article

ArticleThayer School

DECEMBER 1970 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29