One of the best remembered sayings of former President Hopkins during his long and fruitful administration at Dartmouth is that often quoted remark that "too many men are going to college." As usual, one needs the context to discover the real meaning. What it came to, as now recalled, was that too many men are going to college who ought not to go—and too few are going who ought to, in part because the surplus of ought-nots monopolizes the available space. At Dartmouth an attempt is made to restrict the student body to the men who, on the face of the record, have the capacity and the desire to get the most the College has to give, by excluding the obvious drones from the hive. In this attempt, by means of the so-called "selective process," a substantial success has been attained.

One of the midwestern universities is reputed to have made a postgraduate survey of its alumni with a view to ascertaining how much good a college education has done in its own case. Presumably the result will be the usual one, namely that there will be discovered the customary number of men in middle life who went through college without thereby acquiring anything outwardly distinctive to differentiate them from men of equal age who had not the same educational advantage. Every one knows the type; to wit, the man whom no one would suspect of collegiate connections from anything he does, or says, but whom the record avouches to be a Bachelor of Arts. Every college and every university has a plenitude of such. Despite the selective process, Dartmouth cannot deny her possession of a share. The question then arises, does it matter?

There is room for the contention that it does not. Granting that the colleges as a whole are bound to turn out considerable numbers of men with academic degrees of whom no one would suspect they had ever been to college unless they told you, is that fact as important as one might think? For many of us, the really important thing is not what stored-up learning we carry away from college, but what our four years in college inspires us to seek. During our residence we are exposed to beneficent in- fluences; and one idea—perhaps the main idea—is that these shall go on influencing. For it is a trite remark, common to all Commencement and Convocation speakers everywhere, that education is a lifelong process. What the colleges have to give is not a completed education, but a desire for education; not a stock of knowledge neatly catalogued and pigeon-holed in the little gray cells of the brain, but a capacity to think logically, to act cooperatively, and to live appreciatively in the world of men. A man may not be willing between the ages of 18 and 32 to take all the colleges have to offer him; but at least he knows it's there and is almost certain later on to seek it, to what extent he can. It may well be profitable to strive to make all students into ripe scholars, that we may by due diligence save some. The bricklayer when he spreads his cradle of mortar knows that it exceeds what the brick requires, and scrapes away the surplus when the brick is well and truly laid. There seems to be no other or better way.

Too few men are going to college who ought to go. It is well to give them their chance by fending off the too many who go to college who ought not to. The men who ought to go are the men who have the desire, and the capacity, to make the most of their opportunity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleTHE DEAN UNMASKED

December 1945 By HERBERT F. WEST '22, -

Article

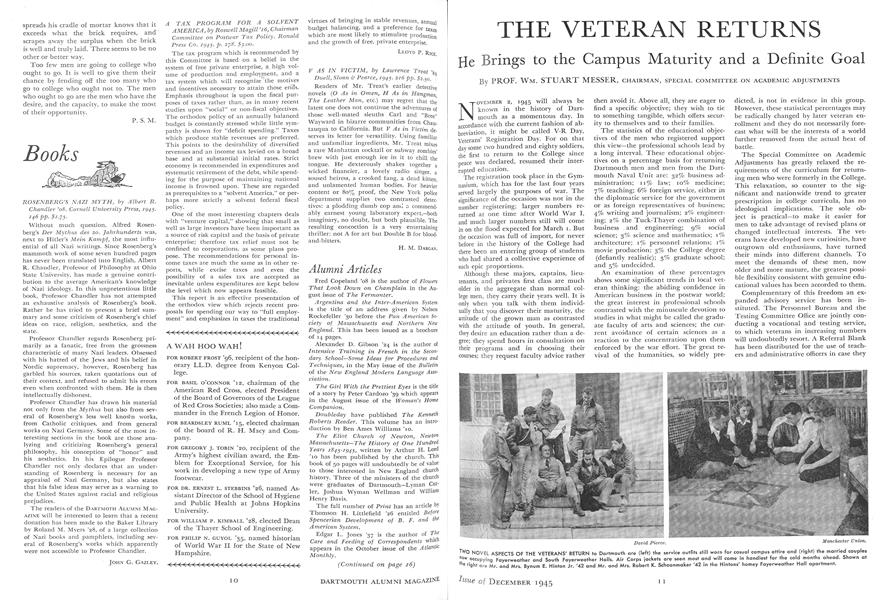

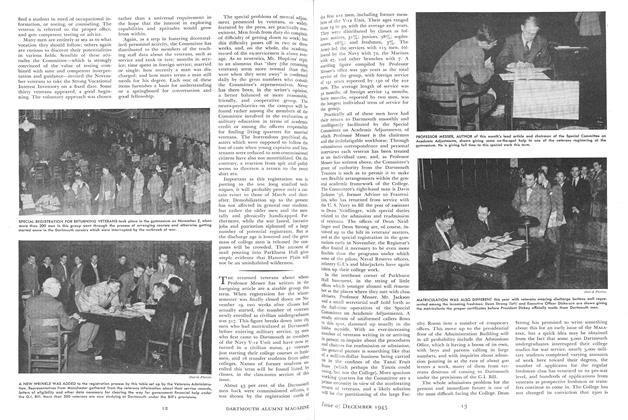

ArticleTHE VETERAN RETURNS

December 1945 By PROF. Wm. STUART MESSER, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1945

December 1945 By ARTHUR NICHOLS, JOHN W. CALLAGHAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

December 1945 By MOTT D. BROWN, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT DICKEY INDUCTED

December 1945 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

December 1945 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

P. S. M.

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth as Unusual

November 1942 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleSacrifice Always Hurts

April 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1943 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleHistory Again

February 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleWho Calls the Tune?

April 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

ArticleEmbattled Independents

February 1946 By P. S. M.

Article

-

Article

ArticleMusical Clubs

December, 1910 -

Article

ArticleFRESHMAN STATISTICS

January 1915 -

Article

Article29TH DARTMOUTH NIGHT OBSERVED OCTOBER 3

November, 1924 -

Article

ArticleSloan Scholarships

October 1954 -

Article

ArticleMorrissey Scholarship Fund

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1983 -

Article

ArticleThe Least Possible Power

MAY 1982 By John K. Van De Kamp '56