AN ISSUE of the MAGAZINE of recent date announced in offhand fashion the appointment of three new instructors to the department of geology. This is all in the day's work, of course—a mere matter of educational record—but those of us who enjoy probing into the past find in the tidbit of news something to mull over at greater length. In our day, if memory serves, the good Dr. Goldthwaite was the whole department of geology unto himself.

Those of us who "took" geology more than likely stumbled into it, perhaps to complete a science minor speedily and painlessly or just possibly to gratify some lurking curiosity about the past performances of the earth's crust. In any case, we got all that we bargained for. To begin with, there was no textbook at all. We simply trailed around the Hanover and Norwich plains behind the Professor's lead, observing where lakes had been a million years ago, what strange varieties of alien rock the glacier had deposited on its way back to the North Pole, and what heavy work of erosion the brooks and streams of the vicinity were still carrying on under our very eyes. That was no doubt what your modern pedagogue would label "motivation." At any rate it was fun. Then suddenly there was a textbook, after all—an alarmingly bulky one—and we perspired our way through one geologic age after another, each characterized by its own bewildering array of fossils. The other was child's play; this brought the consciousness of accomplishment. And to many of us Professor Goldthwaite still comes back to mind as the quiet, unassuming teacher who gave science meaning in the story of the descent of man.

Geology has evidently come into its own at Hanover today, and so probably have history and the social sciences. We remember Eric Foster lecturing before the assembled sections on the Renaissance and Reformation, on Erasmus and Martin Luther; and Charlie Lingley, sending us back to the ancient copies of Alexander Hamilton's "Federalist" to discover whence the institution of capitalism derived its inspiration in these United States. Under his tutelage, also, we delved into the newspapers of the '70's, to find out how Hayes came to lick Tilden and what the fiery editors of the period thought about it all.

It probably isn't so very different even now. There are many new faces on the faculty and new ways of doing things, but for all we know the column may add up in the end to much the same thing. Does Davey Lambuth still conduct his advanced course in poetry? There was an unforgettable moment when that class gathered together for its first meeting and was asked courteously, if a bit dubiously, to write down the name of its favorite poem and to write also the reasons for the selection. At least one of us, in a panic, seized upon Kipling's "If", a selection much easier to remember by title than to defend as poetry. This little essay into higher culture brought nothing but withering scorn at the time of the second meeting, when the class had readily adjusted itself to the proper aesthetic plane; whereas the "Colin's Kiss" of Sara Teasdale was already recognizable as the pure lyric strain. Yet, if you feel that the undergraduate mind has come through chaos to maturity, turn to the newspaper accounts of senior class doings next May. No matter what institution of learning you may be reading about, as you glance down the list of its favorites in literature, you will be in no great danger if you have your money on Rudyard Kipling against the field to carry off the honors in poetry.

Snap courses; hour exams; unlimited cuts. The whole terminology seems as far behind us now as the protozoic age of Professor Goldthwaite's geology class. It is too easy to realize how much we might have learned, and didn't—and a little tragic to discover how hard it is to dig it up later for ourselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

February 1936 -

Article

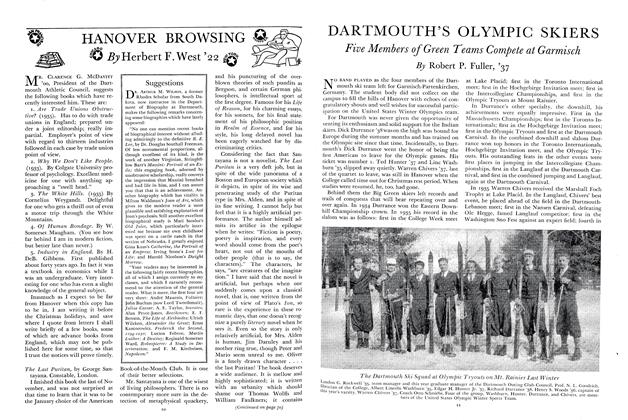

ArticleDartmouth's Olympic Skiers

February 1936 By Robert P. Fuller, '37 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1936 By Prof. Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Article

ArticleEdwin Brant Frost, Class of 1886

February 1936 By Arthur Fairbanks '86 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1936 By Martin J. Dyer, Jr. -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1908

February 1936 By L. W. Griswold

R. M. Pearson '20

-

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

October 1934 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

March 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

April1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

May 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

November 1935 By R. M. Pearson '20 -

Article

ArticleNot So Long Ago

March 1936 By R. M. Pearson '20