"Macmurray's treatment of Art and Religion is the clearest and truest I have found; he's great stuff," says Professor Del Ames. Professor Rees Bowen adds, "He's the kind of man we ought to have on a Guernsey Moore lectureship." "Sometimes I fail to understand Macmurray, and sometimes I disagree with him; but his books are tremendously stimulating—if you read him at all, he gives you no rest." So spoke Dr. Ambrose White Vernon, founder of the chair of Biography at Dartmouth.

And who is this man? John Macmurray was born in Scotland in 1891, graduated from the University of Glasgow in 1913, and did graduate work in Balliol College, Oxford; after five years of war service, and after teaching in Manchester, in South Africa, and again in Oxford, he landed in 1928 in his present position as Professor of Philosophy in the University of London. His amazing success on the radio and with student groups throughout Great Britain brought him to this country last spring, when he undertook a five-month schedule of lectures and conferences, with his usual effectiveness. Short and slight, he wears one of the few full beards in captivity. His clarity of thought and utterance, his gracious and kindly humor, his quiet manner and flute-like voice, his comprehensive grasp of "what's wrong with the world" and his pungent suggestions as to the possibilities of a better future, convinced his thousands of listeners that they were in the presence of a great thinker.

Why should Macmurray's books be recommended for alumni consumption? During the past ten years, he has published ten volumes, in addition to numerous articles. Four of these books were the result of collaboration with others. Of the other six, there are three volumes which should be of special interest to the more thoughtful alumni. Freedom in the Modern World, 1933, Appleton-Century, contains two series of radio talks, presented through the courtesy of the British Broadcasting Corporation. The first four chapters discuss the "modern dilemma"—the conflict between our intellectual conclusions and our emotional life, issuing in a life that is fearbound—which can be solved only through a real religion. After a fascinating historical survey, the author explains what he means by reality, and then shows that freedom is utterly impossible except for real persons. The only true morality is among persons; any mechanical morality through external laws or rules, or any social morality based upon social purpose, is inadequate and therefore false.

Reason and Emotion, 1935, Appleton- Century, defines reason as our capacity for objectivity, and emotional reason as our capacity to apprehend objective values. Twentieth century life is a fantastic travesty of a real life based upon emotional sincerity and objectivity. Our intellectual life—i.e. our science—is mature, but emotionally we are an immature, stunted race; there is no greater need than a sound education of the emotions. Then follow great chapters on the relations between men and women, on the Art of the Future, and on Science and Religion. The book closes with a discussion of Immature and Mature Religion—the only religion that we have known is immature, unreal, largely sham.

The Creative Society, published by the Association Press in 1935 (a fifteen-cent pamphlet form if desired), is in some respects the most interesting book of the whole series. After a brilliant discussion of pseudo-religion, Macmurray presents vividly the religion of Jesus stripped of the myths and mists of the centuries; then a profound analysis of Communism in comparison with real Christianity, and a violent denunciation of idealism in all its forms. The mature religion of the future will be genuine community among men, based entirely upon love, expressed materially in economic interdependence.

Interpreting the Universe and the Philosophy of Communism, both published in England in 1933, are couched in philosophical jargon, tough for the layman. TheStructure of Religious Experience, the Terry lectures at Yale last April (a Yale publication), contains a very illuminating discussion of Science and Art with their conflicting attitudes, and of Religion, which synthesizes the two.

Macmurray, a 100% realist in his thinking, insists that thought and feeling must be based upon nothing but fact, and that unless both are expressed in action they are nothing but nonsense. While there are difficult passages, his many interesting illustrations and his lucid style make him readable. Any student of these volumes is likely to find himself thereafter different.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

February 1937 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1937 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

February 1937 By Rochard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1937 By F. William Andres -

Article

ArticleThe Modern Museum

February 1937 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

February 1937 By Doane Arnold

Roy Bullard Chamberlin

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth Alumni Magazine

May, 1926 -

Article

ArticleTim Ellis Memorial Fund

February 1956 -

Article

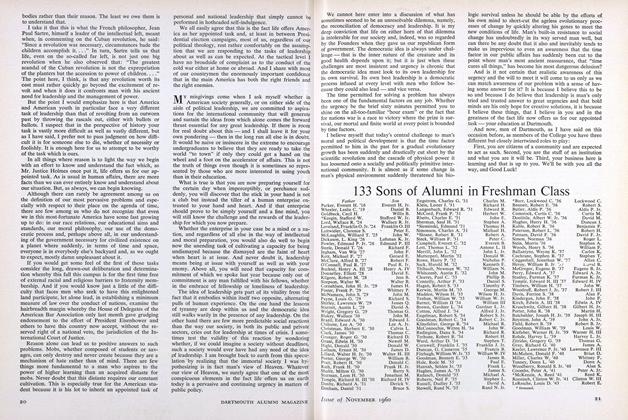

Article133 Sons of Alumni in Freshman Class

November 1960 -

Article

ArticleOff-Campus Study Plans Increasing in Number

APRIL 1966 -

Article

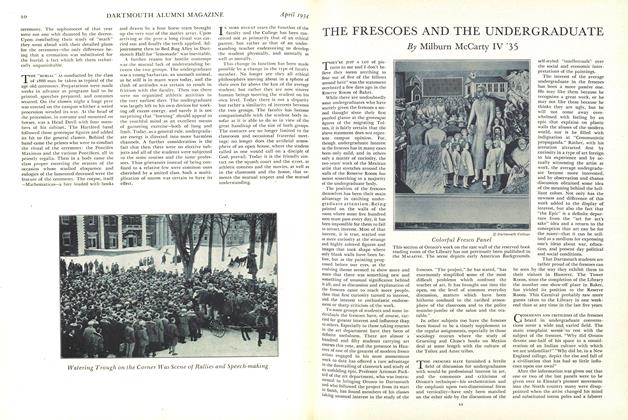

ArticleTHE FRESCOES AND THE UNDERGRADUATE

April 1934 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleTHE FICTIONAL LABORATORY

June 1989 By Noel Perrin and Steve Calvert '68