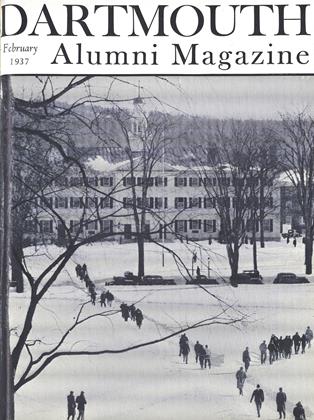

W. WEDGEWOOD BOWEN

Supervisor of the Wilson Museum at Dartmouth

MUSEUMS, large and small alike, owe their existence to two deeply rooted human traits, both heritages from our simian ancestors. The one —acquisitiveness—manifests itself in early life, for example in the child's passion for collecting beer-caps or buttons, and later postage stamps or coins, fading out in most of us as we grow older. The other—inquisitiveness—also manifests itself in early life, but is less apt to peter out with advancing age. Although plainly independent traits in early life these two human characteristics later become so intertwined that analysis of the why and wherefore of museums is no easy task.

Most museums, especially those supported by public funds, justify their existence by stating themselves to be educational institutions, rather than mere places for entertainment. That this self-proclaimed function is in large measure a reality, cannot be doubted, and the great and ever-increasing number of museums in this country demonstrates the public's realization of this fact. But it is a secondary, an assumed role. Not so many years ago museums existed almost wholly because they satisfied man's acquisitive nature, and little or no thought was given to their educational possibilities. Scarcely more than repositories where sundry objects were laid in visible storage, the museums of the past were visited by the curious as are the side-shows of a country fair today.

Even in institutions of learning, collections came into being in a haphazard manner. Curiosities and freaks, gathered in all corners of the globe, as a result of the acquisitive instincts of loyal alumni, found their way back to Hanover where they were laid on shelves in heterogeneous array. A typed manuscript, entitled "A list of the curiosities to be found in the museum at D. College" (unfortunately not dated), now preserved in the files of Wilson Hall, illustrates this phase of museum history.

A few excerpts will suffice.

No. 174-175 No. 177-183 No. 185 No. 186 No. 187 No. 253

Two fragments of the French national prison—the Bastile Mackaroon, the principal food of the Neapolitans and used throughout all Italy & Spain, being excellent for soup .... Cucumber in a bottle, .... Coshoe nut in a vial .... Toulouse adder. The slippers of a Nabob from the Ganges ....

No. 254 No. 255 No. 256 No. 257 No. 259 No. 313 No. 314-315 No. 316 No. 317 No. 318 No. 319 No. 320 No. 321

The Royal George (a man of war, built in London during the late war with England, mounting 130 guns, and sunk by accident before it was got out of the English Channel) in miniature. The Horns of a Sea Cow .... The Zebra. An instrument plowed up in Chesterfield, N. H. The head & horns of an insect .... Chockolate Cocoa. Middlebury white Marble The waters of Saratoga Springs .... A Roman coin .... Hedgehog's Quills. The vertebra of a Whale The knife with which Josiah Burnham murdered the Hon. Rupell Freeman & Mr. Starkweather .... Feather of the Emmew of New Holland ....

What, it may be asked, constitutes a museum specimen? With the growth of the modern museum into an instrument of education, such items as the waters of Saratoga Springs, the horns of a sea cow, or the knife with which Josiah Burnham committed his double murder belong more in the side-shows of our Coney Islands.

The evolution of a purpose—that of stimulating as well as satisfying the intellectual, rather than the morbid curiosity of their public—has brought about a profound change in museums in recent years. Prior to this the acquisition of materials was their sole aim. Row upon row of specimens—stuffed animals, dried insects, freaks, fossils, rocks, and what not—stood upon shelves in glass-fronted cases, often so crowded that many could not be seen, and it mattered little if the labels told no more than a name. Those were the days of classification; names were being bestowed, new species were awaiting description. They were the days of the pioneer. Great work was being accomplished, but the layman who wandered in found himself "out in the cold." No thought was given to his edification. In fact, with the number of species ever growing, and with only vague concepts of their inter-relationships, how could the museum be expected to enlighten the public's mind? But now few blind spots remain for the systematist to explore. That chapter in museum history is drawing to a close.

What, then, is to be the fate of the museum? Is it, and its vast accumulations of materials, to moulder away like a corpse that has lived its day? The answers to these questions are self-evident. Instead of declining, the number of museums throughout the world is on the increase.

Adapted solely for the storage and display of large quantities of specimens, few new lines of research lie open to the museum. Despite some efforts in this direction, the museum cannot enter the fields of anatomy and experimental science, for the simple reason that they are already adequately taken care of by the universities. Yet if the museum were to restrict itself solely to the dissemination of knowledge acquired at second hand it would soon settle into a slough of stagnation. The museum's heritage is its storage capacity, and any new line of activity undertaken should involve modification, not change, of this fundamental characteristic. In what direction, then, should this modification lead?

Field researches and life-history studies of animals and plants in relation to their environment are claiming more and more the attention of museum workers in the biological field, and here at any rate the museum worker and the college worker can meet on equal footing. Moreover, there is here no reason for either to tread on the other's toes, since each approaches the common field from a slightly different angle. Such, then, is the trend of research, at least in the more progressive museums. But what are other functions of museums? Most museums today claim to be instruments of education, and here possibly, there might seem to be some conflict of purpose with schools and colleges. But in reality there can be no such conflict, since the methods of approach are dissimilar, and only a fortunate type of cooperation can result.

Most city museums cater to a public of varied interests and their exhibits must in consequence have wide popular appeal, but in the college museum there is no such necessity and the purely instructional exhibit should dominate. There are more than two hundred university and college museums in the United States, according to Mr. Frank Baker, Curator of the Mu- seum of the University of Illinois. Of these, he writes (Museum Work, Sept. 1924) "notmore than a dozen are functioning in asatisfactory manner and the great majority are of little or no value as an aid toactual instruction. The students of scienceand art are, therefore, being deprived ofa very valuable and potent aid in moreclearly understanding these subjects, besides missing the pleasures and satisfactionderived from a visit to the museum halls,which all students enjoy if given an opportunity." Probably the number of college museums that are functioning satisfactorily has increased somewhat since that time, but there can still be little doubt that they are in the minority.

Where does Dartmouth's museum stand? Can we honestly place it among the minority that are functioning properly? Hardly yet, but increased interest in recent times indicates that things are moving in the right direction. Increased publicity is largely responsible for a growth in number of visitors. The successful museum, like the successful business house, must be publicized and, like the latter, it must also display an attractive line of goods.

A little more than a year ago, in an article in The Dartmouth, I ventured the opinion that Wilson Museum, although rich in material, lacked continuity. I likened it to a number of small museums under a common roof. Perhaps a better simile might be to liken it to an encyclopaedia from which many of the pages are missing. What there is, is good, but there are too many gaps which leave an unsatisfied feeling in the mind of the visitor. Until many of these gaps are filled, and a fairly continuous story can be told through its exhibits, the museum may not hope to occupy its rightful place in the educational life of this college.

Looking towards the future let us review briefly the role which the college museum should fill. Three main branches ofscience are represented—Geology, Biology and Ethnology—and it is to students of these subjects that most assistance can be given, but we must not lose sight of the possibilities which the museum offers for broadening the fields of knowledge of those many students whose chief interests lie in other directions. The museum can exert a broadening influence on the intellectual life .of the whole college.

For the student of the natural sciences the museum can do a great deal by way of filling the blank spaces which, because of time limitations, no prescribed course can ever hope to fill. Just as the volumes in the library play an indispensable part in the college curriculum, so also can the exhibits in the museum do their part. Furthermore, there are some subjects the teaching of which calls for large numbers of specimens and demonstrations. In what more appropriate place may such laboratory work be given than in the museum where the exhibits are permanent and readily available?

The new recognition of Dartmouth's museum leads one to hope that increased attention will be paid to its potential and widespread usefulness in the College community, and that "acquisitive" or "inquisitive" alumni, and other friends, will make Wilson Hall one of their major Dartmouth interests.

Wilson Museum

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

February 1937 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1911

February 1937 By Nathaniel G. Burleigh -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1936

February 1937 By Rochard F. Treadway -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1929

February 1937 By F. William Andres -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1927

February 1937 By Doane Arnold -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1937 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr.

Article

-

Article

ArticleTHE GRADUATES' CLUB OF HANOVER

June, 1910 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Hall

October 1932 -

Article

Article1971 Summer Term Will Offer Series Of Special Programs

APRIL 1971 -

Article

ArticleColby Howe '39: Finding the True Meaning of Fraternity

OCTOBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse

April 1995 -

Article

ArticleEquinox: A Poem of the Hanover Fall Season

November 1932 By Pennington Haile