THERE IS A wide and keen interest in lists of "best books." The weekly summaries of best sellers, both fiction and nonfiction, that appear in the press are examples of the desire of folks who can read to know what everyone else is reading. The popularity of "five-foot shelves" (or ten-

foot shelves), or lists of "my six favorite books" (or the 50 favorites) is evidence of some intriguing quality in this sort of information. From comments heard and received by mail it is apparent that Professor West has a large following of readers among the alumni who are eager to learn what he and other members of the faculty and his alumni correspondents are reading. Except for the necessary limitation on space his monthly "HanoverBrowsing" could run to several pages in every issue instead of a few columns. And it would doubtless be an expansion of an excellent department of this MAGAZINE welcomed by our readers.

Elihu Root Jr. visited Hanover during the year-end holidays. On a tour of inspection of buildings of the College he was keenly interested in the new dining center, Thayer Hall; in the natural ice hockey rink; in the Orozco Murals (which, incidentally, he didn't like, for good and firmly expressed reasons of his own); in the colorful and enticing displays of skiing equipment and clothing on Main Street; in the expanse of acreage devoted to College uses; and in other things. But the place where the tour came to an end (and only closing the Library forced it to be resumed) was the center section of the Tower Room in Baker, where the Kenerson Memorial Library is maintained.

Mr. Root was browsing around idly until his guide remarked: "On the shelves of this alcove are the 1,000 best books of the world." He became, as they say, galvanized into action—an intellectual dynamo. The titles on nearly every shelf were run through. He was satisfied that a very earnest and, in his opinion, a largely successful effort had been made to gather the world's greatest books together in the very heart of the building. (As one of the greatest of all the great books Mr. Root felt that "Alice in Wonderland" deserves a better edition than the one he found in the Kenerson collection.)

THERE WAS bound to be great interest in the announcement made by St. John's College, Annapolis, Md., last fall that henceforth students there may elect to spend their entire four years studying the "100 best books" of all time. Apparently educators at St. John's believe their colleagues in other institutions were mistaken during recent years when they shifted from the study of the ancient and modern classics to special professional training, or to the current emphasis on the social sciences in the colleges. Certainly the experiment at St. John's goes back to the classics with a vengeance. "Gone With the Wind" is not on the list. There is nothing included that has been published more recently than certain works of Freud, James, and Russell and Whitehead.

Upon request the editor will be glad to mail copies of the St. John's list—the entire curriculum for those students who elect it —to the curious among the alumni. We will even publish the list in the next issue, if interest prompts a few readers to request that this be done.

THERE IS A very faint, but discernible, trend toward an emphasis on recovering the classical disciplines that the early generations of students in American colleges knew so well. Perhaps "trend" is overstating the occasional motions that one observes are made in this direction. The St. John's experiment is a new approach, in our generation, to the always present problem of stimulating the minds of students; of giving a young man a sound education and the ability to think clearly and act wisely: but also giving the student some comprehension of the world and the society of which his college is a part, and into which he will shortly go.

The most recent change in the Dartmouth curriculum was aimed at the last of these objectives. Social Science 1-2, required of all freshmen, seeks: (1) to create a lively interest in contemporary social, economic, and political problems and the capacity to approach such problems from a critical and yet tolerant point of view; (2) to provide a wholesome respect for facts, a sense of time sequence and a common background of factual material for advanced work in the social sciences; (3) to emphasize the interrelations rather than the differences between the social sciences.

Social Science 3-4, designed for sophomores who are not going to major in a social science, treats such important topics of today's life in this country as: business, money and banking, labor agriculture, race, family, consumer, church, government, crime, propaganda, and international relations. The teaching staffs of both courses are drawn from the faculties of the various social science departments.

THE DESCRIPTION of the two new courses in the curriculum, already familiar to many alumni, is given here only to illustrate the statement made earlier in this discussion that there is some evidence of a growing interest in the classics in the colleges. Your definition of a classic and mine may differ. Not all classics were written in Greek or Latin, or composed by the masters of English Literature. Social Science 1-2, for freshmen, covers the period from the middle of the 18th century to the present. It is primarily European in content and assigned readings are made from the historical and social classics of the period. The course itself, however, is hailed as modern and progressive.

LET US NOW turn to that super and youthful educator, President Hutchins of Chicago, whose recent published work includes "The Higher Learning in America" (Storrs Lectures at Yale) and a series of articles in the Saturday Evening Post. In both of these contributions to letters of the day there is a facile use of the wise crack that the reader either enjoys or that goads him into extreme mental alertness, depending on whether he is for or against the proposition.

President Hutchins claims that the higher learning in this country is in a great dilemma. Of the colleges he says, in his Yale lectures, the current purpose is "to turn out well-tubbed young Americans who know how to behave in the American environment. Association with one another, with gentlemanly professors, in beautiful buildings will, along with regular exercise, make our students the kind of citizens our country needs." He infers that this is the general idea that most people have of life in the colleges—at least "we have no coherent educational program to announce."

His greatest concern, and here he finds the greatest dilemma, is with the universities. This is natural and appropriate since he is the president of one of the greatest and largest of the country's universities. His experience with liberal arts colleges is limited.

He finds a tremendous emphasis on professionalism in the universities. Students are there largely for the purpose of fitting themselves for a career; their concern is with vocational training. There is an "increasing practice of pointing work from the junior year onward toward some professional school." "My contention is," he says, "that the tricks of the trade cannot be learned in a university, and that if they can be they should not be."

The solution of the problem is to provide for a "general education"—apparently a nation-wide scheme to give everybody some education, and to prepare the wellqualified for entrance into the universities. The gap of two years between high school and university will provide mass education of a general nature by a great expansion of the junior college system, which is now growing rapidly. Then the student will enter upon a purely intellectual pursuit of education in the university of his choice, studying under one of three faculties"metaphysics, social science, and natural science." After a period of years the student will go to law offices, hospitals, churches, or construction jobs to learn the "tricks of the trade."

REFERENCE HAS been made in earlier paragraphs to the observable trend toward a greater emphasis on the classical approach to educational policy. President Hutchins outdoes all the others. The St. John's plan fades into insignificance in comparison. The Dartmouth required course with its students concentrating on a classical background of modern European and American history (but with "green grass, beautiful buildings, and gentlemanly professors" still left on the campus) falls short of his pure intellectualism. Although Dartmouth, and other colleges of liberal arts, have resisted temptations since their charters were granted to teach vocations they are apparently condemned to extinction (in favor of the junior colleges) because their students take regular exercise and band together in extra-curricula activities.

There is a similarity between the Hutchins argument and the theories of Dr. Alexis Carrel who hopes for a world populated, some day, by supersouls. This will be accomplished through the establishment of "institutes of psychobiology" and an "institute for the construction of the civilized man." President Hutchins wants the work of the universities to be "wholly and completely intellectual." And there will be no colleges.

The plea for a general raising of intellectual standards in the universities is probably sound enough. We are not qualified to say. He is. But the force of the argument loses its punch when anyone offers to resolve the dilemmas of education by depriving students of a collegiate life that is aimed to fit them for a fuller and richer existence—no matter what career they later choose, or what tricks of the trade they learn, or where they learn them. "The impact of youthful mind on youthful mind" —in classroom or on the campus—has been stated by President Hopkins, in recent addresses to the alumni, to be one important element in the college process. A plan of education that leaves out of consideration the desirable balance between the intellectual, the social, and the physical components of the College ignores decades of patient endeavor that have gone into its curricula and extra-curricula structure.

Our contention is that the variety characteristic of American education meets the problem of higher learning in this country. Professor L. B. Richardson has stated the point admirably: "Institutions iritended to satisfy a multiplicity of needs exist with us, side by side,each serving a field of its own. The studenthas only to consult his tastes and desires tofind among them the one which best meetshis particular demands. They are in noreal sense conflicting institutions."

The craving of President Hutchins for educating the intellectual specialist is answered in a few of the leading universities. The liberal arts colleges (whether they are separately endowed institutions or are attached to the few privately endowed universities) are giving a broad educational and collegiate experience to men who may later enroll in the professional or graduate schools.

WHILE THE universities are busy reorganizing under the Hutchins Plan, and the junior colleges multiply by addition and division, do we hear any bids for Dartmouth Hall?

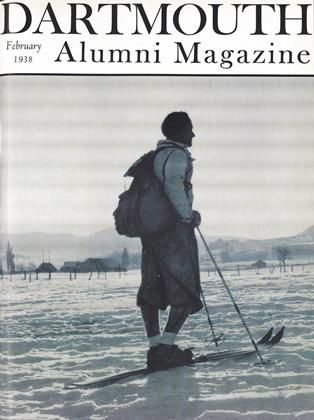

THE COVER this month is the result of combined efforts of Dick Durrance '39 and his brother Jack '39. Jack is the subject, in a characteristic pose of the cross country skier. Dick is the photographer. He is a rabid Leica enthusiast and would probably rather be known as a first rate photographer than as the Number 1 skier of the country. As a matter of fact he is entitled to high rating in both activities. The cover picture, a careful piece of photography made with a Leica camera (which uses the so-called "postage stamp" sized negative), is a good example of Dick's work.

He is a leading contributor of pictures to the Dartmouth Pictorial. His prowess in this art has earned him a job as photographer at Sun Valley, Idaho, next summer. Neither he nor his team mates dare guess how many pictures Dick made on the skiing trip to Australia and New Zealand last summer. "How many?" the boys are asked. They smile and say "Thousands." Dick says "Hundreds." Evidently there are quite a few, of which a selection will be published in this MAGAZINE in the customary Undergraduate Issue, the April number.

ALTHOUGH SOME old timers were inclined to scoff a bit when the winter sports bug bit the public hard two or three years ago, now even the natives of New Hampshire and Vermont are withdrawing funds from their savings accounts to bid for the tourist skiing trade.

A "Dartmouth Open Slopes Region" has been organized to promote the attractions of Woodstock, Hartford, Fairlee, Orford, Bradford, Hanover, and Lebanon as centers for skiers. The reports are that there are some 18 ski tows within these towns and there are more to come. The Hanover Inn, under the energetic new management, has flooded an area behind the hotel and has connecting this skating rink with the main dining room by a flight of steps. Not only is evening skating enjoyed by the guests, as an aid to digestion, but on occasion luncheon is served on the ice. Tables are distributed over the surface and guests are served by waitresses on skates.

THIS DEVELOPMENT at the Inn prompted Bill Cunningham '19 to comment in his column in the Boston Post as follows: "But it's the big ad about the Inn, on the back page (of The Dartmouth) that really gets the veteran of the days when the winter was hell—even if hell in reverse. It shows a big photograph of six tables full of couples, having dinner out of doors in the snow;. It's a very pretty scene with lots of snow around the fringes. The customers are all extremely intent upon their victuals, but some, at least, are without hats or heavy coats. Two waitresses in white dresses are moving around, and a bus boy, bare headed and with no coat over his uniform, is apparently sliding a tray onto or off of a table.

"The caption says, 'Skiers enjoying a skating interludeduring dinner served on the skating rink between the Hanover Inn (lining room and the Ski House.' Not until I copied off here did I realize that there's nothing especially formidable about that 'interludeduring.' I thought it was one of those fancy German ski terms, but I now see it's only 'interlude' and 'during' telescoped together by the good old-fashioned variety of typographical error.

"But, even so, if anybody had ever set up a table out of doors in my time, they'd have summoned the booby squad and arranged for reservations in Concord.

"And, says the ad, going on, 'We haven't had so much snow in years—the skiing is perfect—the skating is wonderful; sleigh bells are jingling and it is a good old-fashioned winter. Your big question still is HOW MUCH?'

"And then it quotes its rates, and they look engagingly reasonable, but imagine that 'We haven't had so much snow in years .... it's a good old-fashioned winter.'

MT. ASCUTNEY, 20 MILES AWAY, AS SEEN TO THE SOUTH OF HANOVER

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe D. O. C. Started Something

February 1938 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1914

February 1938 By Edward Leech -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1937

February 1938 By Donald C. Mckiniay -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

February 1938 By Hap Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1930

February 1938 By Albert Dickerson -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

February 1938 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr.

The Editor

-

Article

ArticleIn Memoriam

October 1935 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

July 1940 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleNext Month

May 1941 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleGRADUS AD PARNASSUM

June 1941 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleAlumni in Service

June 1941 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleOvertones in Time of War

October 1942 By THE EDITOR

Article

-

Article

ArticleThe Diamond Peaks on Dartmouth College Grant

May 1912 -

Article

ArticleMUSICAL CLUBS TOUR

May 1920 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Club Luncheons

October 1948 -

Article

ArticleWith Big Green Teams

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleThe Hanover Scene

May 1955 By BILL McCARTER '19 -

Article

ArticleThe Dean's Shiny Nose

November 1956 By WILLIAM R. LANSBERG '38