LAST NIGHT, lightning struck the massive radio tower on the summit of Mt. Washington. It rang out like an iron bar hit by a sledge hammer. There was no damage. Today, the wind has picked up until now, with a stop-watch and a telegraph sounder to time intervals between contacts, I have just clocked a gust of 163 miles per hour. But according to the graph, the mean for a five minute interval is 120 miles an hour. Still, the actual gusts, which we are unable to catch, must be well up towards 200. Doubtless, that is what is rocking the Observatory so unevenly.

A stone, probably not even a large pebble, has just been blown against one of our fine $50-a-sash windows to drill a hole through the outer pane. It is well that the sashes are double-glazed.

If this were only winter, a thick coating of ice or rime would protect us. The rain is beating in around every door and window. Some of the ordinary glazing in the vestibule is jaggedly missing. And we seem to be inside a giant packing case which some super-Paul Bunyan attempts to batter in.

The chief observer stumbles upstairs, drenched to the skin, reporting that the railing of the Summit House platform has blown away and that the platform itself will quickly follow. The manager of the hotel calls on the tieline to ask that we check the line down the mountain. Dead.

Boston does not answer our call on the radio. Blue Hill Observatory's frequency is silent. Friends in Seabrook and Exeter do not come on when we call. Only Pinkham Notch is on the air, but they are wellnigh isolated without a telephone line and the road tree-strewn. Increasingly the broadcast programs are interrupted by flood and hurricane reports; personal messages and assurances.

A politician asks that we preserve our faith in God and the Commonwealth.

The barometer shoots upward. The rain decreases, and the wind's faint jarring of the building lulls us to sleep.

The morning is sunshiny and blue with cumulus clouds hitting us only occasionally. Two windows are gone from the Stage Office and its interior is very damp. So is the hotel, with bald boards showing where the shingles have been ripped off. Our rain gages are tipped over or blown away. Planks lie about among the rocks. Nobody answers our radio or telephone calls, so we put on a constant signal for identification and start down the railroad trestle which carries the telephone line.

The Base does not answer but the summit does until we get down a little below the "Skyline." There a rail has pulled away from another. Odd. And below that is an awe-inspiring sight—all of the "Long Trestle" and "Jacob's Ladder" has lurched crazily northward, in places it has turned completely over. A whole half mile, at least, of track is so much kindling and scrap iron. The road, too, is blocked and will require much axe work.

And even as I write, the rest of the world knows nothing of these things.

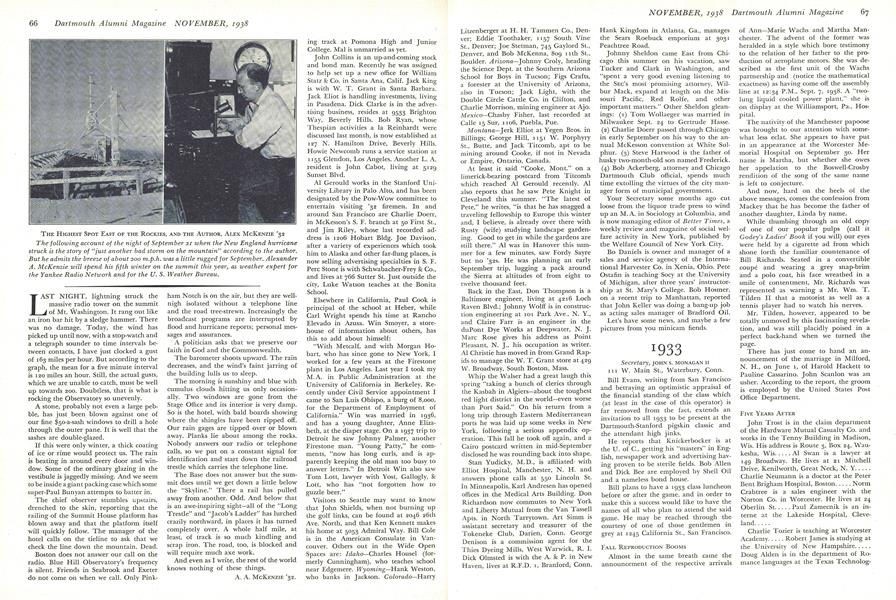

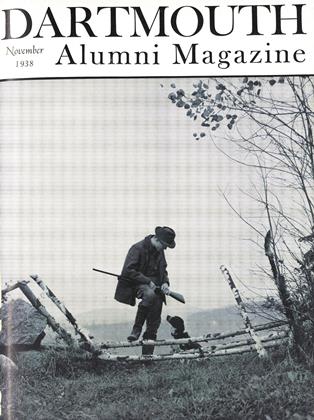

THE HIGHEST SPOT EAST OF THE ROCKIES, AND THE AUTHOR, ALEX MCKENZIE '32 The following account of the night of September 21 when the New England hurricanestruck is the story of "just another bad storm on the mountain" according to the author.But he admits the breeze of about 200 m.p.h. was a little rugged for September. AlexanderA. McKenzie will spend his fifth winter on the summit this year, as weather expert forthe Yankee Radio Network and for the U.S. Weather Bureau.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

November 1938 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

November 1938 By "Whitey" Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleGradus Ad Parnassum

November 1938 By The Editor -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Rebel Saint

November 1938 By ALLAN MACDONALD -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917

November 1938 By EUGENE D. TOWLER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

November 1938 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR.