ONE OF THE challenging proposals made last month by James Bryant Conant in his Annual Report to the Board of Overseers of Harvard University is the formation in the United States, of a large number of two-year colleges, aided by federal funds, to meet the increasing demand for education beyond high school. For the vast majority of their students, these colleges would terminate formal schooling by bringing to completion a general education, though exceptional students might of course go on to higher education at a regular college or university. "For many types of students," says President Conant, "a terminal two-year education beyond high school, provided locally, seems better adapted to their needs than that offered by a traditional four-year residential college."

President Conant sees the need of a rapid development and expansion of such two-year colleges, controlled locally, but aided by both federal and state funds. "For example," he says, "the Hill-Thomas-Taft bill has been framed to provide for federal aid for public education without federal control of education. If such legislation should become law, and I personally hope it will, I see no reason why some of the money flowing to the states should not be used in supporting the local two-year terminal colleges. At all events, to the extent that such educational facilities are rapidly expanded and improved by the use of state and federal money, the increased demand for post-high-school education might be largely met."

Conant's proposal carries out his thinking of some years ago, as witness his report to the Overseers in 1943: "For surely the most important aspect of this whole matter is the general education of the great majority of each generation—not the comparatively small minority who attend our four-year colleges .... today, we are concerned with a general education—a liberal education—not for the relatively few, but for a multitude." The proposal seems directed toward the eventual ideal of a statesupported college education—of sorts—for all citizens.

To private four-year liberal arts colleges, the suggestion may seem at first blush to promise dangerous and undesirable competition the competition between state and private education and the possible danger of bureaucratic regimentation, and the competition of lower standards a sort of educational price-cutting war between the new two-year colleges and the traditional four-year institutions.

SLUMP IN COLLEGE ENROLLMENT UNLIKELY

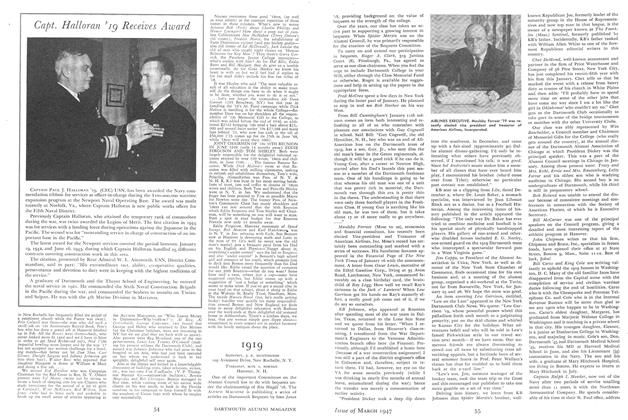

If, however, we examine the dimensions of the whole problem of higher education confronting the United States, such fears seem groundless. It is well known that college enrollments have grown steadily. In 1870, American colleges enrolled 80,000 students; in 1940, 1,500,000. In seventy years, in other words, while the general population increased threefold, college enrollments increased thirty-fold. The number of students at present enrolled in institutions of higher education is said to be over two million. While the present large number of veterans may lead us to suppose that total enrollment will go down in a few years, who can be sure that it will? It did not after the last war; indeed it stayed up and increased throughout the 'twenties. Education is contagious, President Conant says, and "one of the consequences of the present influx of veterans into our colleges and universities will be a demand for the younger brothers and relatives to have similar opportunities."

A college education seems to be part of the new American dream. As the insurance advertisers realize, every father and mother hopes for a college education for their children. Who can tell that the curve of increased enrollment of the past seventy-five years will not continue upward during the next twenty-five? Suppose it does: what is our maximum potential higher-education market? In 1940 there were seven million students in secondary schools. If all of these —or, to be conservative, only three-quarters of them, as was true in 1870—went on to college, our college enrollment would reach five and a quarter million: more than two and a half times the present "emergency" congestion! Though this is quite unlikely to happen, the overall picture is nevertheless one to make "competition" for students seem the least of our worries, even if we chose to take so selfish a view of a problem so closely bound up with the national welfare.

SEES FOUR-YEAR STANDARDS RAISED

Would the competition of lower qualitative standards in two-year colleges injure higher education in the traditional fouryear institutions? The answer here is a clear "no"; on the contrary, standards would quite probably be improved. Every college teacher knows that a goodly percentage of the two million students now in institutions of higher learning are incapable of higher learning. They are in college because of the new American dream: because it is the "thing to do"; because it is a mark of social status. Such students do great harm to American higher education: they waste their own and the colleges' money; they waste invaluable time when they might be learning or doing some other thing of real worth to themselves and to society; and quite often they are tragically unhappy. The worst of this damage, probably, occurs in the junior and senior years, when students who have no real interest in things of the intellect for their own sake are forced, willy-nilly, to choose a major and to do advanced and specialized work that must seem to them at the best dull and useless and at the worst destructive of their self-confidence and hope.

It is to be anticipated that the new twoyear colleges would draw a large proportion of such students away from the fouryear colleges. The "general education" afforded them would not seem too offensively useless; they would get out into some job that interested them two years sooner; and last but not least; the change would save papa about three thousand dollars per child and sorely-strained college budgets a like amount.

TWO- YEARS PROVIDES NATURAL BREAK

There is a natural break in the educational process which comes—normally—at the end of sophomore year. The break has been marked, implicitly at least, in the curricula of Dartmouth and other colleges for many years. We require certain courses in freshman and sophomore years to achieve breadth of background and intellectual development. After this stage has been completed, we permit the student to choose a major, and allow him great freedom in his choice of courses in junior and senior years. This is a crucial change. It marks the boundary between general education and higher or specialized education; it assumes that the student has enough educational maturity to choose and follow his later course of learning. If, however, the student makes no vital and genuine individual choice, if he is not ready for or does not really want a higher and individualized education, the choice of a "major" is a travesty.

It would be a particular advantage of the two-year college that an institutional break would coincide with this educational break. The poor student would be encouraged, in effect, to get out and get a job, and the good student would pursue a higher education only as a conscious and resolute choice. Students of this sort, transferring into four-year colleges or universities, would be welcome arrivals.

No such two-year colleges as President Conant proposes are likely to equal the qualitative standards of the traditional private liberal arts colleges. Since they would be designed to attract more millions of secondary school graduates than now go to college, they would of necessity have few or no selective admission requirements. Even with federal and state aid, they certainly could not equal the resources in faculty, library, buildings and equipment of the established colleges. Administered somewhat, I imagine, as now are the large city high-schools, they would tend toward the large-scale mass-produced education that now characterizes many of the state universities. So it would be foolish to regard them as any sort of educational Utopia.

But it would be equally foolish to deny that any system which might make it possible for millions of American youths who cannot get into existing colleges, or cannot afford to go to them, to obtain at least a general education such as befits every citizen in a free society would be a valuable contribution to American democracy.

The cost, of course, would be large. But we already cherish the ideal of free public education for every boy and girl through secondary school, and are willing to pay more for it than we do for anything else in our civil life except war. We regard such expenditure as a public investment in society's future, returnable in the increased productivity and intelligence of our citizens. If we believe that America's dream in past generations of free public education for all boys and girls up to sixteen has been a sound one, why stop at sixteen?

The two-year college seems a valid proposal in the economics and politics of higher education in America. It would complete for many more millions of students that general education which is desirable for good citizenship; it would give a broader base of worthwhile candidates for higher education; it would satisfy the social aspirations of many millions of American families for what could, with some justice, be called a "college education," and yet would eject into jobs all those who are not able and eager for the higher education of junior and senior and graduate years; and by this last token it would improve the standards and accomplishment of American higher education as it now exists.

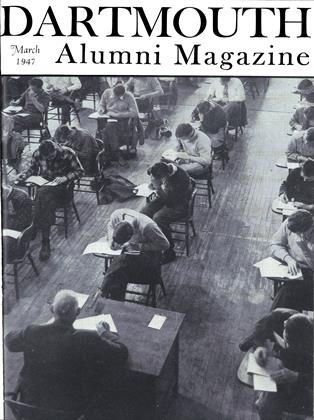

DARTMOUTH HALL, IN WINTER GARB, CATCHES THE AFTERNOON SHADOWS OF CAMPUS ELMS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

Article"Free as the Air"

March 1947 By JERRY A. DANZIG '34, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1947 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Article

ArticleRadio Interprets the News

March 1947 By CEDRIC FOSTER '24, -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937

March 1947 By JOHN H. DEVLIN, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Article

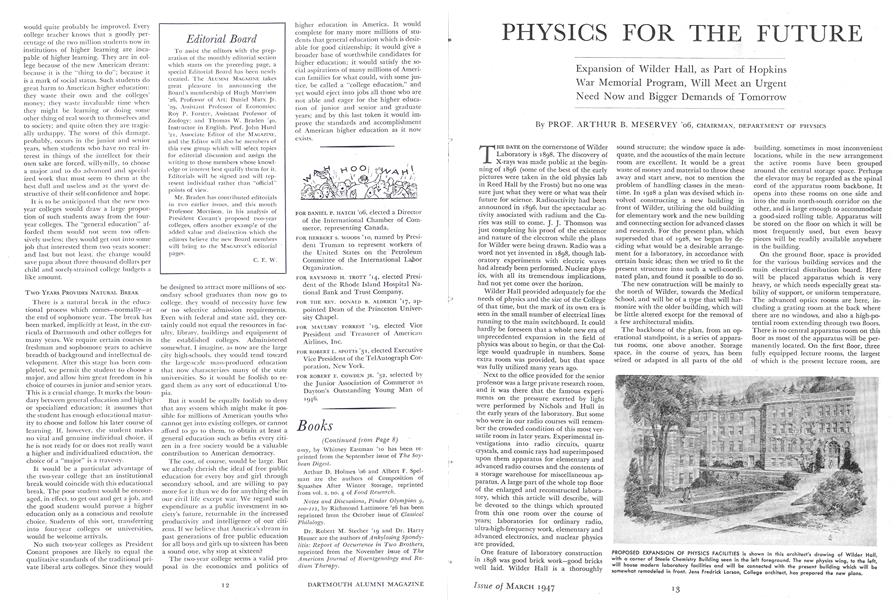

ArticlePHYSICS FOR THE FUTURE

March 1947 By PROF. ARTHUR B. MESERVEY '06. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

March 1947 By DONALD G. MIX, ROBERT M. MACDONALD