TRIP OF THE UNITED STATES TEAM REVEALED NEWHIGH ALTITUDE SNOW FIELDS BELOW EQUATOR

DARTMOUTH MEN may be justly proud of the selection of five Big Green skiers to represent the United States on the snowy slopes of South America during the past summer. This group was invited by the Ski Club of Chile to compete in their country. It was an extremely generous gesture to attempt to foster interest in annual PanAmerican ski meetings. A word of thanks and praise is also due the Grace Steamship Lines for their generosity and hospitality.

New York was somewhat perplexed and not a little in doubt as to the sanity of this group of green-clad exponents of the hickory blade, when, on a hot and sultry June tenth last summer, they marched en masse with ski equipment over their shoulders through the streets of that city. It does appear peculiar until one realizes that while we on the northern half of the universe are preparing for swimming, tennis, and boating, the people below the equator are turning their thoughts toward the cold winter season.

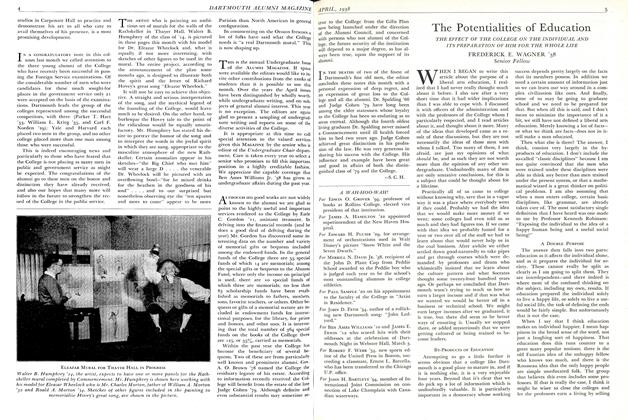

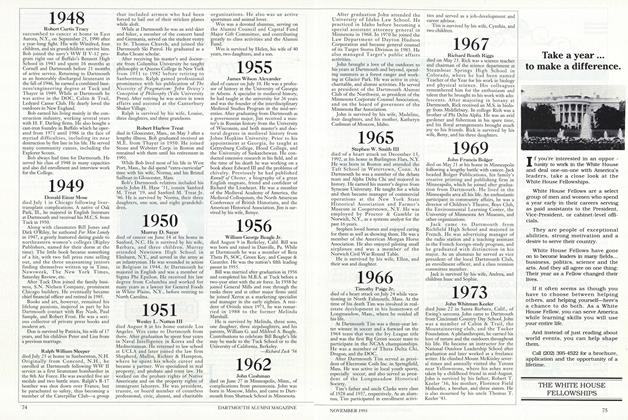

The men who carried Dartmouth's banner "down under" were Capt. Warren Chivers '38 and his brother Howard '39, sons of Prof. Arthur H. Chivers '02, Ted Hunter '38, Ed Wells '39, and John Litchfield '39. The remainder of the team was comprised of Don Fraser from the University of Washington, and Eugene Du Bois, from New York, who acted in the capacity of manager.

Leaving New York, on June eleventh, we had a calm and very interesting trip down. None of the newcomers to sea travel was sea-sick, much to the disappointment of the more hardened oceangoers in our group. Days of blistering hot sunshine and nights of cool ocean breezes occupied the majority of the trip as far as the Panama Canal. Frequently interspersed in these days of heat, and nights of stars and moonlight, were hours of dancing, ping-pong, shuffleboard, deck-tennis, and the ancient Indian art of tippling. A far better description than I could possibly give of the more personal aspect of our trip can be found in a small book entitled "Skis in Andes." It is very well done by Mr. Dußois and contains interesting and valuable material and hints for any person who is considering a South American cruise of any sort.

From the Canal to Valparaiso, Chile, we experienced a new sensation that of being compelled to put on additional clothing each day, as we gradually drew farther and farther away from the equator. Taking almost three weeks for the passage, the members of our group were afforded ample opportunity to see much of the country at whose ports we stopped. We, here in the states, often think that the people in our cities live lives of poverty and degeneracy. I often wondered, on our trip, what these same people would think if they stopped over a day or so in some oil town on- the western coast of South America. We were very much impressed by the filth and squalor in which the natives of these lands exist. Rationalizing, this can be explained by the fact that these people know of nothing better thus they have no incentive to improve their condition. Despite this rational outlook there still remain the smoky mud huts, diseased and deformed weeks of humanity crawling and groveling in the streets, unsanitary meat and food shops, vice districts, drunkenness, and muddy, garbage-strewn ruts which are called streets. An atmosphere of slow, lazy, lethargy pervades these coastal towns.

IT'S A SMALL WORLD

Despite the fact that we were three weeks away from the Indian tepee, we were overjoyed to learn that the warwhoops from the hills of Hanover had even been heard in Chile, and that Dartmouth was known in this far-off section of the world, thanks to reports taken into that country by native Chileans who travel through Europe and a few who have visited the United States. Through them reports of Dartmouth's fame have echoed through the ski world of South America.

We were warmly greeted by a group of Chilean skiers at the docks in Valparaiso. The delegation which met us was headed by the president of the Ski Club of Chile, Agustin Edwards, a very fine and thoughtful man whose interest is one of the main cogs in the ski machinery of Chile. From Valparaiso wTe journeyed inland to Santiago, where we were once again shown a sample of true Chilean hospitality, in the form of excellent dinners, wines, hours of jovial comradeship, and very comfortable sleeping quarters.

Due to the fact that we arrived in Santiago early in July and the winter was just setting in, we were taken by a group of Chilean skiers a thousand miles farther south to Osorno where we stayed for a week and then returned to Santiago in time for the Pan-American Championships. Here, I was taken sick with glandular fever, which kept me in bed the remainder of our stay in Chile. However, the other members of the team had some wonderful skiing and, performing in grand fashion, succeeded in capturing the Newell Bent Trophy from the best Chile had to offer. This is the first year that any competition between Pan-American countries has been conducted thus it is significant that Dartmouth has played a prominent part in this first northern victory.

Skiing in Chile is an infant sport. It is now in the stage that it was here in the United States about 1928-30. A few more years will be necessary to raise the brand of skiing to the level of other countries. In a comparison between Chilean skiing and that of other countries we found that it was more like skiing in the Alps or the western part of the United States, than it was like our eastern terrain. The skiing which we did this summer was all done above tree-line, which means wide-open snow fields without hindrances such as rocks and trees. Here in the Eastern United States we are accustomed to narrow, twisting, bumpy trails, so we were overjoyed to be able to skim over the spacious white slopes, putting turns in where we wished, ungoverned by a set course of maddening curves and terribly solid trees which often seem to loom out of nowhere in the path of the skier. Despite the wonderful terrain, we seldom hear of Chile as a skiing country because these vast expanses of snow are just becoming appreciated.

In direct contrast to the mountains of the United States, the Andes are extremely lofty peaks often reaching a height of 23. 000 feet. This necessitates much traveling and climbing before good ski country is reached. A lack of good roads makes traveling slightly hazardous and the miles and miles of excellent ski territory haven't as yet even been scratched. The people haven't even begun to dream of the pos. sibilities which are theirs for opening one of the ski countries of the universe.

Progress in skiing is going to be slow because of this lack of adequate traveling facilities plus the fact that skiing is a very expensive sport in Chile. The climate in the cities is always sub-tropical, which means one must climb to an altitude of 7,500 feet or more to find snow. That is a definite handicap and so it is only the well-to-do people who can afford to enjoy the sport. However, with the introduction of European ski teachers and the unbounded enthusiasm of the Chilean skiers, the sport should make marked progress in the next few years.

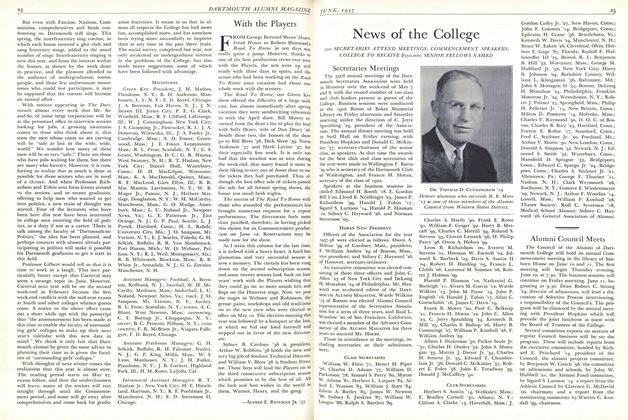

U. S. TEAM IN CHILE: WELLS, HUNTER, LITCHFIELD, DEWOLFE, EDWARDS, W. CHIVERS, FRASER. (HOWARD CHIVERS NOT IN PICTURE.)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleIn Search of Snow Down Under

April 1938 By DAVID J. BRADLEY '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Potentialities of Education

April 1938 By FREDERICK E. WAGNER '38 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

April 1938 By BEN AMES WILLIAMS JR. '38 -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1937

April 1938 By Donald C. McKinlay -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1910

April 1938 By Hap Hinman -

Class Notes

Class NotesClass of 1934

April 1938 By Martin J. Dwyer Jr.

Article

-

Article

ArticleDetroit Dinner

APRIL 1932 -

Article

ArticleBurn the Rest

May 1980 -

Article

ArticleTake a year... to make a difference.

NOVEMBER 1993 -

Article

ArticleWith the Players

June 1937 By Alfred E. Reinman Jr. '37 -

Article

ArticleSheepskin Season Recalls a Mystery

June 1953 By Alice Pollard -

Article

ArticleThayer School

April 1948 By WILLIAM P. KIMBALL '29.