Undergraduate Editor Ends Occupancy of Chair with Prose Ode to the Class of 1939

THE Class of 1939 wasn't here when they lopped the Colonial steeple off the old Chandler Hall Indian School and added an Italian balcony, icecream cone roof, and a flank of monstrous pillars. 1939 wasn't around when they constructed Tuck School, raised dormitories, moved Choate House or built Baker either. The graduating class wasn't even here when Dartmouth Hall burned. . . . . 1939 wasn't around during the big period of Dartmouth's physical expansion.

Grant you, it did watch Dartmouth Hall rebuild and see them take down Chandler brick by brick. It took in the erection of the Thayer eating hall and the new Thayer School of Civil Engineering, watched them add a cafe onto the Inn, stood in the street and gaped as the Campion block burned, experienced the melting transformation of the old low-ceiling Nugget into a professionally new one. It saw several new fraternity buildings go up. It witnessed a couple of floods which didn't damage Hanover. It helped clean up after a hurricane which did. It saw a lot of Cement sidewalk replace dirt paths and gazed at plans for a milliondollar theatre-auditorium.

But 1939 missed the big period o£ Dartmouth's physical expansion. It boarded the train, came to Hanover, got out its freshman handbook, learned the rules and looked at the buildings. After four years the buildings are substantially the same. . . . The rules have changed.

Rules? . . . yes, they're changed. Stop to think. Old Timer's Day is gone. The Delta Alpha parade is gone. So is the Nugget Rush and throwing stuff at the shows. Likewise hazing and hose fights in dormitories. So also the College taproom and so also, Pledge Night. We're not waxing nostalgic—we're merely trying to point up the disappearing vestiges of a small happygo-lucky Dartmouth, a sentimental Dartmouth, if you will.

We're trying to show the emergence of the big, serious, professional Dartmouth ... a new Dartmouth like the last four years' football and sports teams. Like the Players and the Experimental Theatre, like the modernized Dartmouth format and office organization with secretary and complete files. Like the football rush with its organized sprinters, like THE ALUMNI MAGAZINE, like the DOC and its Carnival spectacle—big, serious, professional.

The new Dartmouth is getting more serious, more responsible, more organized like its Topical Majors and social sciences, its responsible-student unlimited cuts, its extensive supervision of fraternities and athletics and .. . . activities. Very much like the extra-curricular activities, the new Dartmouth is a broadening Dartmouth.

Modern Dartmouth has a truly broad string of activities, and with the lack of definite College policy on extra-curricular activities—each organization admittedly pumps for itself and piles it on for its own interests—challenges inactive men.

Despite this process of interest-enrichment there's been a lot of carping lately about turning Dartmouth back to what it once was, about "giving it back to the students," about throttling over-publicity and commercialization. There's been carping about students being forced into extra-curricular activity against their will and actual interest, by over-promotion.

Give the College back to the student, indeed! Extra-curricular activity in the role of castor-oil, indeed! Where did the extra-curricular activity implicit in the essence of liberal arts training, come from? It came from the natural student desire for self-expression apart from the routine of the curriculum. Simplify all these growing interests for richer lives, a richer College, a richer liberal arts training—what for? What can be the criticism of professionalism and its promotion (if it isn't overdone as perhaps is the Carnival fracas) if professionalism means excellence and progress? Take away one sector of worthwhile undergraduate activity and you are removing one cluster of students benefiting thereby. Simplification indeed! Merely a phrase!

There's no need getting sore about this, but after all let's not go back to the cart, the outhouse, and the ice-cake refrigerator.

The buildings are substantially the same .... the rules have changed, and the Class of 1939 has watched professionalism, seriousness and bigness skirt the Campus and close in on it.

At about this point the Alumnus must imagine the modern Dartmouth student to be a somber-faced dub, minus the normal attributes of youth-optimism, gayety, etc. And concernedly the Alumnus might ask by virtue of the changes and the disappearance of many of the old traditions .... about the Dartmouth spirit. Does it still hang around, and if so where does it come from in an age trended toward this professionalism and seriousness?

The Dartmouth spirit exists today and it doesn't come from any particular element. It doesn't come from the dining rooms of the fraternities, for instance; the fiaternities which are undergoing a justifiable but somewhat mystical process of rejuvenation with the College wanting fraternities strong, but itself stronger. All right, you say, if the spirit doesn't come from specifically any one element—where does it come from? That intangible living spirit sometimes called "democratic" but inadequately so, just comes from the Plain of Hanover, and four years on it. It's the town, the faculty, the students, and the environment. The graduating class of 1939 knows it as the graduating class of 1772 knew it—although the contributing elements are different.

For the Class of 1939 that much heralded spirit is... . well, it's President Hopkins at Convocation, physical exams and Rec credit. It's the grave of the Yale Jinx and hanging to the rope of the Chapel bell. It's the eastern sky on a pink frosty morning, the neon lights on Main Street, twelve o'clock in the Wigwam, heelers' ratings on the bulletin boards, and the Christmas service in Rollins Chapel.

The Commons orchestra and meat balls and a boiled potato, Smith, Vassar, Skidmore, Green Key and Carnival, furniture moving, favors for upperclassmen, Pledge Night, Delta Alpha, and rushing the Nugget.

A small pea-green hat on a large peagreen freshman, 2 P.M. concentration on an hour exam, Industrial Society in Choate House, Evolution with stellar slides in Silsby and Wilder with the automatic curtains and Prof. Gilbert and his turntable and equipment demoralization timed at intervals to wake people up after full dinners. It's Geology with the Varves and Bayoux of Mink Brook, the smell of fresh ink off The Dartmouth press, the makeup room before a Players show, the developing solution in the Camera Club.

Edward Tuck, Nat Woodward and Tames Campion Sr., the fireside in a cabin on a DOC hike, the Dartmouth Bookstore and travel circulars at Joe D'Esopo's bureau, midnight feeds, Safier's Studio, swing music, skis on Balch Hill in winter, the Connecticut River, the Plain, and Balch Hill in spring. Waiting at White River for the train, sleeping in Tower Room chairs, and the fire bell ringing in the middle of the night. Parents sitting by the fireplace in the Inn looking approvingly at students. Letters in the mail slots, bull sessions, sun baths on the dorm roofs, duckboards and baseball.

It's late afternoon conferences and lifediscussion with profs in small offices through windows to the green trees outside—and it's even Amos, beer-can Herby, Geranium, Abernathy, and all the rest of the dog characters including whimsy sophisticated Terry, the 8 A.M., 12 M., 6 P.M. Thayer Hall mascot with the paper napkin around his collar.

STILL MAKING THE DARTMOUTH MAN

It's these things—it's all these things, and it's even more, and they all make a 1939 Dartmouth man a Dartmouth man. They lay hold to him and they mold him to a sort of pattern and when he gets to the end of his senior year, big companies who have found him a fairly standard product and a good investment, come to the Personnel Bureau and take him away.

In four years the Class of 1939 has observed not so many physical changes, has nevertheless watched seriousness and professionalism justifiably creep about the Campus and close in, and, soaking itself in four years of Dartmouth—see itself a Dartmouth class.

Is there anything else? Not much now except the graduation diploma and a general 1939 eye to the future—all kinds of eyes: the politician, the writer, the chemist, the doctor, the business man, the social worker, the professor. All eyes are on success, and success to the graduating Dartmouth man probably means concerted effort and individual achievement in any direction that brings status among his fellows and offers some satisfying contribution and progress to an increasingly professional world.

In the past, stock nostalgia for the paragraph before the Undergraduate Chair is hauled out from under its occupant in April is: "I've liked the job, I'm sorry it's all over, I hope the Alumni, etc." But I'd rather not slop over. You see I'm getting in training for graduation when they bring out the band and the mortar-board hats, and the black robes over green grass. So I'm going to be tough, and merely remark casually about the job on the ALUMNI MAGAZINE as part of Dartmouth-three words: "I liked it."

As a hopefully suggestive final word: however,—here comes another ardent con tributor to the Alumni Fund.

On Campus

Some activities have been stopped, and a lot more like outdoor baseball practice have been hampered by a spring which Hanover weather prophets have proclaimed as the latest in 14 years—but not in the hindered-activity category is Paul Sample's work.

Paul Sample goes right on with his student life class, sketching in black and white from models on Tuesday nights. And rain or freeze, on Thursday afternoons Paul Sample and his undergraduate class, including various faculty and Administration members—Dean Neidlinger, Professors West and Macdonald, Architect Larson and son—work with colors up on the top floor of Carpenter Hall. If a Thursday afternoon happens to be warm and springlike the whole troupe emerges to the great open and paints landscape.

Paul Sample, Artist in Residence, came to Hanover to spread to the student body the gospel of fine arts. "Painting is not the mysterious art-form many hesitant undergraduates may think it is," says Mr. Sample, and you can see that he is intensely interested in one good way of getting young people to make satisfying use of their spare time. "Students don't have to be professional," he emphasizes. "All they have to do is be interested." That's one of the encouraging things Mr. Sample finds about his work. His courses aren't required and they don't give academic credit, and he is sure all the twenty students in his life class and those in the costume class are doing what they are for the interest, the creativeness, and the satisfaction of it.

Paul Sample's men have worked along and made progress and around Green Key this year there will probably be a community exhibition of what they've done.

Dartmouth has found its way to most corners of the sphere, but the last two years have reserved themselves a special niche in the world-to-conquer category. Or would a special mound be more accurate?

K2 is the third highest mountain in the world. It's in the Himalayas in India and it's never been climbed. Last summer Yale-graduate Bill House and party tried to climb it but they ran out of food after they'd fought upward in zero temperatures, swirling snow, and icy winds 26,000 feet to a point encouragingly near the summit.

This summer Chappell Cranmer '40, George Sheldon '40 and Jack Durrance '39 of the Dartmouth Mountaineering Club are going to try it under the leadership of Fritz Weissner, mountain expert and friend of Bill House.

Climbing a mountain like K2 is a very large order and to prepare for it Undergraduates Cranmer, Sheldon, and Durrance, who climb mountains for the challenge of it, have already left for Asia for preparations for the summer-ascent. Cranmer and Sheldon left with the rest of the party March 17. Durrance who suddenly decided he wanted to conquer K2 also, left later.

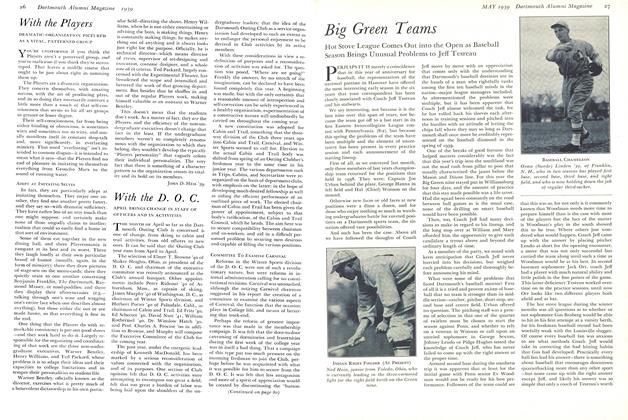

There's been bountiful undergraduate activity at Dartmouth during the past four weeks. There was mid-term, in the first place, and hour exams. There was the Interfraternity Play Contest with its high percentage of fraternity-participants, there was the highly adequate annual Variety Night showing of undergraduate talent climaxed by Gilbert and Sullivan's Trialby Jury featuring such notables as bewhiskered Dean Neidlinger, fiery Joe D'Esopo, and Professor George Frost-in an anniversary of their playing the same piece together a number of years ago.

"Spring" vacation descended on the Campus and students underwent the usual process of taking books home and bringing them back, with no reports of broken bindings.

The Players are currently undergoing and have undergone showings of the Abe Lincoln play Prologue to Glory and Ayn Rand's Night of January the 16th, while four undergraduates get ready to put on their original one-act plays in the Experimental Theatre contest the 19th of this month.

In a very few days, May 6 in fact, Green Key with all its spring trappings will take the spotlight and everybody's going to have a very festal time with the special Saturday Night climax in the Alumni Gym with Larry Clinton and Jimmy Lunceford, big-time favorites in the dance field.

It's a little over three weeks to comprehensives, then finals and graduation; out with the Class of 1939, parole for '40, '41 and '42, and in with the Class of 1943 as Dartmouth undergraduate history surges alarmingly ahead.

UNDERGRADUATE EDITORRalph N. Hill '39 of Burlington, Vt., whoends his occupancy of The UndergraduateChair with this issue. He has also been associate editor of The Dartmouth, a member of the Band, and a successful studentplaywright and actor.

DARTMOUTH "CHORINES" Band members participating in Gilbertand Sullivan's Trial by Jury at the VarietyNight program on March 24 included,front row, left to right, John White '41,Swift C. Barnes '42, Charles C. Mackinney'40; back row, Harry Maxwell '41, John G.Moody '40, and Joseph M. Kipe '41.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue