"The Logarithm Is as Dead as the Dodo" and Other Revelations of Six Scientific Sections of the Faculty

PROFESSOR OF MATHEMATICS

[This is the third of three articles describing the Divisions of the Faculty—theHumanities, Social Sciences, and Sciences.Professor Brown has served as chairman ofthe Division of the Sciences— ED.]

THE DIVISION of the Sciences comprises the teaching staffs of the Departments of Biology, Chemistry, Geology, Graphics and Engineering, Mathematics and Astronomy, and Physics. It is a democracy with a rather strong regard for States' rights, and it has thus far shown considerable unwillingness to extend Federal authority. The other two Divisions meet in the evening in carpeted drawing-rooms and discuss weighty matters of educational policy in well-rounded phrases. The Division of the Sciences holds its sessions in the late afternoon in an underground room whose inadequate ventilation helps toward an early adjournment.

The teaching in any department of science falls into three rather clearly separated categories. First, and most important, is the teaching of the elementary courses elected by freshmen and sophomores. Second is the teaching of the group of courses elected by those who enjoy science, and who make it their major interest. Third is the teaching of the advanced courses, some of them of graduate calibre, elected largely by the younger in- structors and assistants in these departments.

Taking up these categories in reverse order, we find that the Departments of Physics, Chemistry, Geology, and Biology make a practice of keeping on a number of recent graduates, as assistants. These men are working for their degree of Master of Science, and a considerable amount of advanced instruction is offered for their benefit. This advanced instruction is not the entering wedge which might change Dartmouth from a college to a university. It is, in fact, given by older men in addition to a rather full program of elementary and intermediate in- struction. It is stimulating to the teacher as well as to the student, but it does not loom large as a first duty of the teacher.

MACHINES FOR MATHEMATICS

The intermediate courses, elected by men majoring in one of the sciences, seem to be pretty satisfactory. That these courses are somewhat technical does not disturb either the Division of the Sciences, or the students who elect and enjoy them. It is perfectly true that 99 per cent of the Dartmouth juniors have no interest in Celestial Mechanics. But talk to one of the six juniors in Professor Haskins' course, who comprise the one per cent who do. He will tell you that he has just completed the determination of the orbit of an asteroid, and he has 42 pages of computation which he will show you whether you are interested or not. If you are unwise enough to ask him facetiously if he hasn't worn out a table of logarithms on the job, he will reply quite seriously: "This course includes the newest developments and methods, and every fellow in the class has his own computing machine. And of course, for ordinary computation purposes, the logarithm is as dead as the dodo."

But the most important part of science teaching in a college of liberal arts is the teaching of the introductory courses. It is also by all odds the hardest job. Its difficulty and its importance are both recognized at Dartmouth. In too many institu- tions, the teaching of the introductory courses is thrust on the youngest teachers. Here, very much the reverse is true. The Catalog of Dartmouth College lists its faculty in order of service at Dartmouth. Of the first 14 names on the list, 10 are members of the Division of the Sciences with services aggregating some 350 years. Nearly all undergraduates come in contact with at least one of that group. More than that. Any student taking any introductory course in science will receive in- struction from a man of more than ten years' teaching experience at Dartmouth, and on the average his instructor has taught 22 years at Dartmouth. Perhaps this will only strengthen the conviction of the reader that the Division of the Sciences is composed of doddering old wrecks.

The faculty of Dartmouth College requires every student to elect year-courses in two different sciences, but it does not specify which courses. In fact it is not easy to find any field of science, or even any small plot of which one may say "Every educated man must know something about this." Such benefits as the radio brings us may be enjoyed with no knowledge of its interior. Spinach does whatever it does independent of our familial ity with vitamines and enzymes. But all of us are living in a physical universe which is complicated and at times seemingly haphazard, and yet one which does possess certain laws. Many men have experimented, framed hypotheses, tested them, and put laws together into a framework. They have made mistakes, they have guessed wrong, but they have made progress. They have organized and systematized facts so that a few laws and principles cover a great many situations. They do know what will happen under certain conditions. They are responsible for a great many things which affect us very intimately. We are better prepared to live, and to enjoy life, if we find out something of what these men did, and how their work adds up.

No SURVEY COURSE

Which is the better thing to do? Teach physics and geology as typical sciences of the 1939 vintage, or attempt to organize a general science course which integrates all the sciences in a consistent and harmonious whole? The three Divisions of the faculty have all faced this problem of a general course, and have given it the most careful consideration. As the two previous articles in this series have explained, the Division of Social Sciences has adopted such a general course, while the Division of the Humanities has not. The Division of the Sciences believes that a general course in science is not in the best interests of Dartmouth College.

In arriving at this conclusion, the Division was considerably aided by a student committee which I appointed after a series of editorials in The Dartmouth had voiced the rather decided disapproval of a few students with the present requirements. This committee turned in a remarkably able report. Of special significance to us was their unanimous belief that a general science course for freshmen or for sophomores was not desirable.

It is not surprising, and there is nothing inconsistent in the fact that the three Divisions should come to different conclusions. Behind these decisions there is a willingness to consider and adopt the new when it is good, and an unwillingness to follow a trend which seems to offer more loss than gain. Specifically, the Division of the Sciences shows no tendency to be stampeded into unwise action by scornful comments on water-tight compartments. Conditions are often such that a water-tight compartment is an extremely useful place to work in. It is easy, but it is quite wrong, to picture chemistry and botany as two adjacent, neatly plowed fields with a barbed-wire fence between; and it is easy and still wrong to demand the removal of the fence. A better picture of these two sciences is that of two partially explored domains with a howling wilderness in between, through which run a few badly marked trails on which you travel at your own risk. Nor was the Division impressed with the simile that the first thing to do is to take an airplane survey of the whole kingdom of science. If the simile is worth anything, which is doubtful, it should still be pointed out that an aerial survey is rather valueless when you are continually in a thick fog.

ELEMENTARY EMPHASIS

Of greater importance is the constant effort of the Departments to adapt and improve their introductory courses. This effort is not spectacular. The specific changes in the last few years, and there have been many, are not impressive, nor would they furnish very entertaining reading. Yet we feel that this constant effort is the most valuable contribution we can make to Dartmouth College.

I do not, however, wish to leave any impression that the Divisional set-up is an unnecessary encumbrance on the scientific Departments. It provides a smooth, orderly procedure for business which is our common concern. While the Division has not hunted around for busy-work, it has not dodged any issues which have arisen. I wouldn't say that there has been any great increase in co-operation and friend- ship. We've always seemed to get along pretty well together—probably the watertight compartments help.

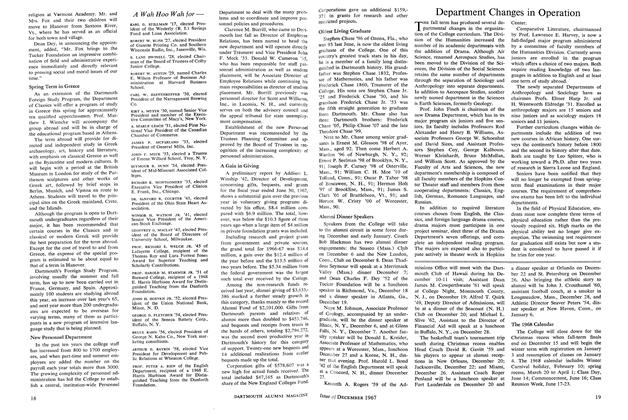

ELDEN B. HARTSHORN '12, CHEMISTRY DEPARTMENT Professor Hartshorn is chairman of the department of chemistry. A top grade student inchemistry and varsity D man in track is Edward F. Hammel '39, also shown above.

MATHEMATICS CHAIRMAN The author of the accompanying article,Prof. Bancroft H. Brown, has also served aschairman of the Division of the Sciences.

PROFESSOR NORMAN E. GILBERT, CHAIRMAN OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHYSICS; AND (RIGHT) PROFESSOR CHARLES J. LYON, BOTANY TEACHER WHO IS CHAIRMAN OF DEPARTMENT OF BIOLOGY.