Changing Trends in Hanover Require Greater Flexibility Without Surrender of Standards

THE FIRST OF LAST DECEMBER, the faculty of Dartmouth College was to a rather remarkable extent united in its opinions on world affairs. That this country would in the near future become involved in war with the Axis powers was considered inevitable by nearly all; that it ought to declare war was believed by the majority. The events of December 7 were a surprise; but the immediate reaction was: "War had to come, and it's a good thing it came this way."

A good many classes on Monday morning, December 8, began in some such way as this: "I am not entirely unaware of the events of yesterday, and of the declaration of war which this country will certainly make within the next few hours. It is not the business of this course to consider these events or their consequences. Our job right now is the subjunctive in the fourth conjugation." That was the expressed opinion that morning, it still is. It wasn't the easiest thing then for either the instructor or the student. It is still the hard thing; it is still the thing we are doing.

Almost fifty years ago when Dr. Tucker assumed the presidency of Dartmouth College, he announced the policy: "It is always and everywhere the function of the College to give liberal education, beyond which and out of which the process of specialization may go in any direction and to any extent. The College must continually adjust itself to make proper connection with every kind of specialized work, not to do it."

With that policy the administration and the faculty are in full accord. Not that a pronouncement of Dr. Tucker is sacrosanct—thought it would be a foolish man who without careful thought challenged one of his matured convictions—but that is the policy in which we have faith. And faith is hard come by these days, and not to be thrown away carelessly.

So the department of chemistry is teaching the same courses it has taught previously it has not scrapped them for intensive work in plastics, ersatz rubber, and high explosives. The department of physics still talks about heat and light and mechanics; it does not spend all its time on electronics and high frequencies. The department of mathematics and astronomy still teaches analytic geometry and the calculus; it has not changed its courses to exterior ballistics and navigation.

But the continual adjustments of which Dr. Tucker spoke are being made, as indeed they have been made for years. Students who have the background of funda- mental knowledge, may have time to learn a good deal about plastics and electronics and navigation at Dartmouth. And if time and exigencies prevent a fuller study, experience shows they can make "proper connection with every kind of specialized work" later. I have mentioned only three departments, because those are the three that I know something about, but this could readily be extended to the other twenty-four.

"WORK HARDER AND LONGER

Yet it would be very wrong to imply that the war has made little impression on the faculty. We are deeply concerned for the College, for the students, for our families, for ourselves. We don't know what is ahead, any more than our students do. But the faculty does not cover its uncertainty by talking all the time. Long winded discussions just aren't the order of the day. There is less and less talk about the duty of society in maintaining a community of scholars in cultured leisure. There is less and less fuss about the inalienable rights of a professor to protection, sabbatic leaves, and leisure for reading and research. Instead there is quiet and ready acceptance of the fact that we must work harder and longer. Education twelve months in the year is going to present problems. Students are restless and irritable; so are we, but we mustn't show it. Students have in the past had more time to think and read and prepare long papers. We have got to be flexible, and see that we can make different demands, less tiring demands, without any surrender of standards. Our most pressing problem right now is that it is March, March in Hanover, and no long spring recess to look ahead to. A few students, possibly a few instructors, overflowing with self-pity at their hard lot, will be washed away with the spring floods. We can endure their loss.

Discipline, obedience, strict observance of routine; should these dominate the college o£ to-day? On this question more than any other, the faculty would differ. But I think the majority of us would be sorry to see Dartmouth College adopt all the methods of an army camp. Perhaps we have given our students too much personal responsibility, some have failed, but a surprising number have not. One of the greatest satisfactions that comes to a teacher is to write a letter of recommendation for a student whom he has seen grow and develop and assume responsibility, particularly when it is possible to finish with the words: "I recommend him without reservation."

There is in college teaching a considerable cleavage between two types of instruction. There are small classes in philosophy, literature, art, and the social sciences generally, in which the give and take of class room discussion is the obvious and correct procedure. On the other hand there are disciplines in which discussion is futile- the multiplication table is an exampleand in these classes the instructor teaches what he knows. There is no conflict between these two types of classes, and in a college of liberal arts both have an important place.

In the main the elementary courses in science belong in the second group. The number of students electing these courses has increased. College seniors who haven't looked at algebra since their sophomore high school days are flocking into elementary classes in mathematics, grimly determined, and not a little frightened. The necessity of "one year of college mathematics" for training for commissions in nearly all of the branches of the armed services, is the spur behind this trend. There are other trends, and there may be still more in the future. Now the faculty pledges that it will meet every legitimate demand on it. And we will meet it with our regular staff. We will not turn over these classes to refugee scholars, nor to inexperienced assistants. We know this will mean less opportunity for reading and research; we know it will mean no sabbatic leaves for the duration; this is our job.

MAY HAVE LARGER CLASSES

We are going to insist on doing this job, and doing it in our own way. Those of us who have taught disciplinary, fundamental scientific courses in the past have been too willing to follow blindly the practises which are correct for our colleagues in other fields; but which are not the best for ours. In the past our classes have been too small, and we have gone crazy over "expression" and the attempt to develop discussion. What I predict for the future is a sharper division between "discussion groups" and "discipline classes." I should like to see the division exaggerated. It will be in the best interests of all. A class of 60 or 80 in trigonometry is not a makeshift, an unavoidable consequence of crowding in war times. In certain subjects it is the logical way to do things.

The physical plant of the college reflects the trend of the last two decades toward universally smaller sections. There is an abundance of small rooms well suited for class discussions. That is good, we need them. But the rooms on the Dartmouth campus which are adequately lighted and which will seat in comfort 100 men, can be counted on the thumb of one hand.

Assuming that at some not too future date, Hanover is to be bombed, it might be well to practise some evasion on our extremely effective and vigilant air raid wardens, and arrange for a few well-lighted targets. I have indeed heard high administrative officers speak wistfully of welcoming beacons on the roofs of Rollins and Webster Hall. I will not enter into that, but I have a few simpler desires of my own.

Several heavy demolition bombs to take down the trees to the east of the Shattuck Observatory which block off a good many stars in the eastern sky. These will have to be very large bombs, as even the hurricane of 1938 failed to do an adequate job.

One small incendiary bomb for the Wren Room in Sanborn House. This should be extinguished as soon as the immaculate atmosphere has been changed to dingy comfort.

Several judicious light demolition bombs to take out partitions in some of the college buildings, and yield a few class rooms in which 60 men can sit with elbow room and a clear view.

One highly discriminating bomb for the College Catalog, which shall permanently delete about twenty courses which we have been giving because we want to ride a hobby, or because some other college gives such a course, or because we always have given this course, or because the course looks well in the catalog.

This article is written for the alumni of Dartmouth College, not for professional educators, not for the administration nor the faculty nor the students of Dartmouth College. It has just one purpose: to tell you that the men you knew, the men you suffered under and worked with, are going to stay on the job. There will be changes; but the Dartmouth you knew will survive: Indian summer, and snow, and March, and arbutus; contest and friendship; discipline and free discussion; growth in character and knowledge, and search for wisdom and truth.

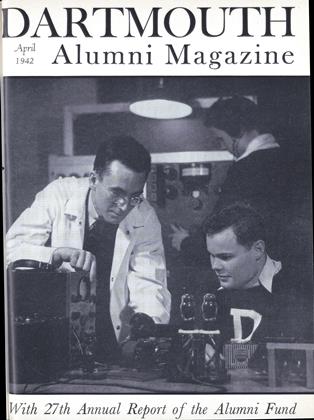

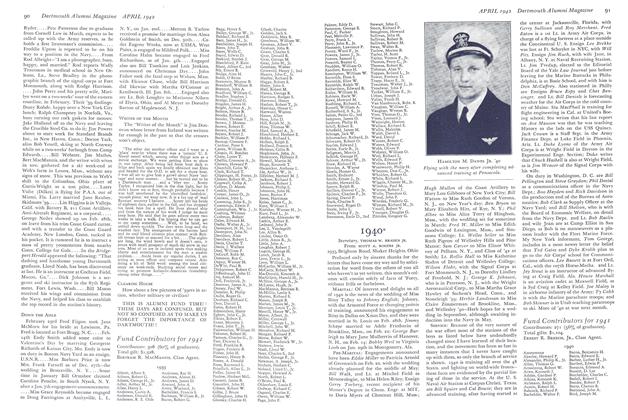

COURSES IN PHYSICS PREPARE STUDENTS FOR SERVICE Carl H. Nordstrom, shown above with student, is a new teacher in the department ofPhysics this year. He is a graduate of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. Because of the valueof both basic and advanced instruction in Physics to men preparing for the armed forcesor for employment in war industry and other services the work of the department hasincreased. Prof. Gordon Ferrie Hull who retired from teaching in 1940 has been recalledto duty this year.

PROFESSOR OF MATHEMATICS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

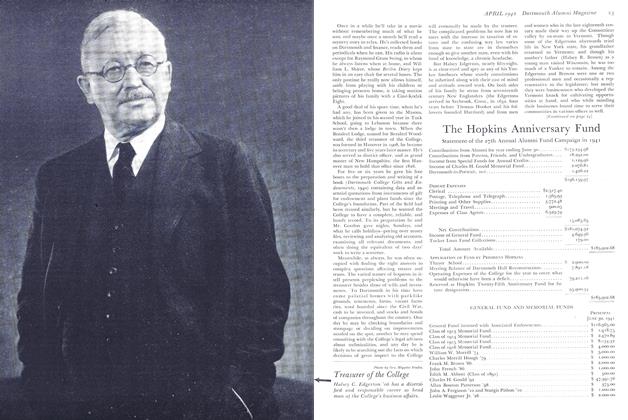

ArticleManager of College Finance

April 1942 By ARTHUR DEWING '25 -

Article

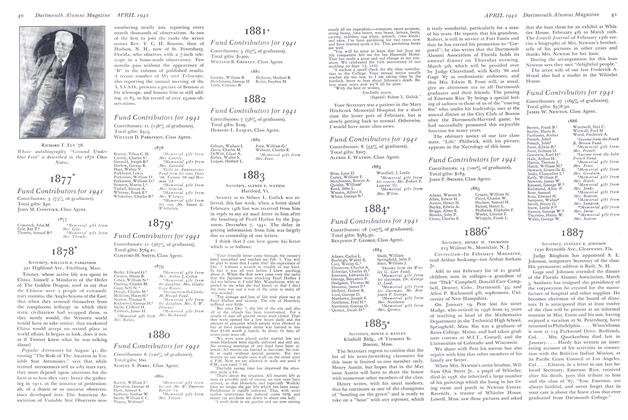

ArticleAssociated Schools-Fund Contributors

April 1942 -

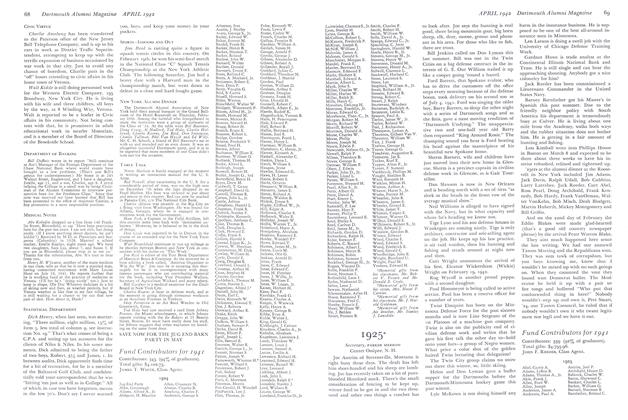

Class Notes

Class Notes1924*

April 1942 By A. A. ADAMS JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1926*

April 1942 By ROBERT E. CLEARY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

April 1942 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939*

April 1942 By RICHARD S. JACKSON

BANCROFT H. BROWN

Article

-

Article

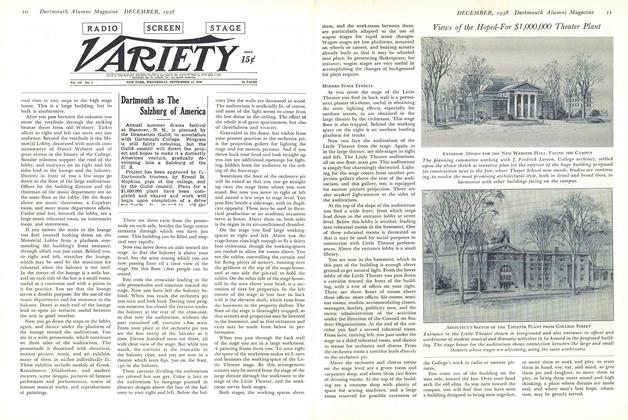

ArticleDartmouth as The Salzburg of America

December 1938 -

Article

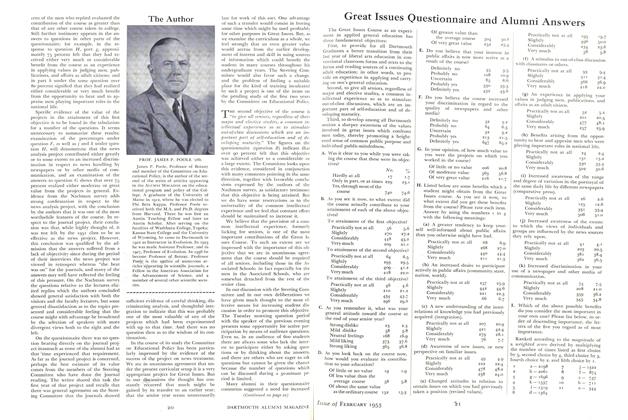

ArticleGreat Issues Questionnaire and Alumni Answers

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleJust Teething

September 1995 -

Article

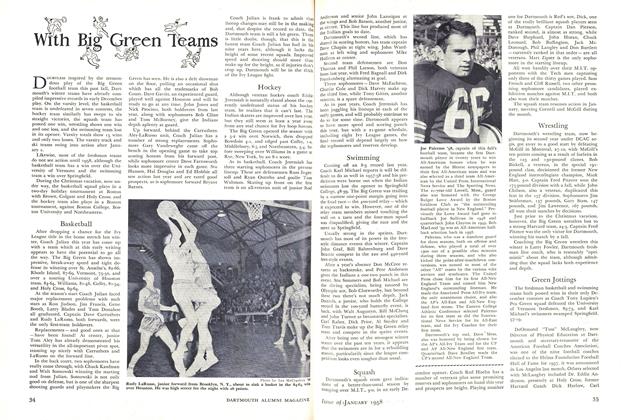

ArticleWrestling

January 1958 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

November 1949 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

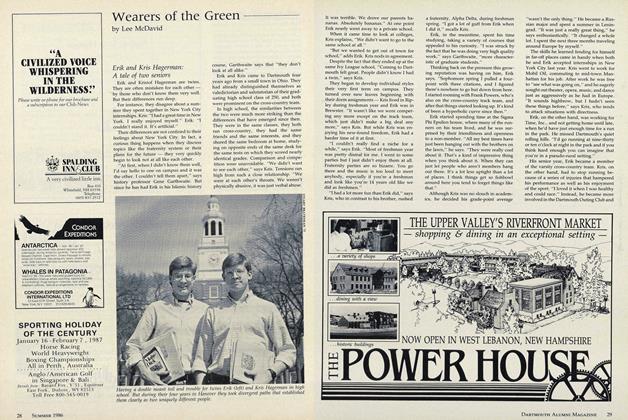

ArticleErik and Kris Hagerman: A tale of two seniors

JUNE • 1986 By Lee McDavid