Is There a Spiritual Impulse Responsible For Our Faith in Enlightened Freedom?

IT WAS NO ACCIDENT which drove men to America. There is nothing purely fortuitous in the desire for "enlightened freedom." On the occasion when Thomas Paine vehemently called us to remember that our heritage is not solely English but continental as well and pleaded that we maintain a place of refuge for the oppressed of Europe; when, almost a generation earlier, angry colonists demanded of the crown not separation but the enjoyment of such freedom as belonged to Englishmen at home; when Washington tried to steer a safe course between Hamilton's desire to concentrate authority and Jefferson's belief in dispersing it—this "spirit of America" was no legally formulated thing such as later took shape in a constitution and a congress and a court. It was one more uprush of that irrepressible "Quelle" at the core of human personality which, like a spring in the winter's woods, murmurs underground until it somewhere breaks through its elemental crust to reflect the light it is seeking. It was an expression of that same spirit which we were taught as youngsters on Thanksgiving Day and Fourth of July when we were told that our fathers sought a land where they could worship God as they pleased. If the phrase has become hackneyed and stale, there is within it a real fountain of faith which still runs free. In short, our belief does take form in social behaviour and in political growth. Our dependable democratic processes are but the expression of a man's intuitive feeling that he is a part of a developing "culture." For our background provides us with no mean blend of French, Dutch, Italian, Swedish, German, and English influences. If culture implies anything, it implies a sense of having a history and having a philosophy about it, an idea of why one's nation came to be and where it is going. This consciousness on the part of some of us is really but a sense of "enlightened freedom"—the result of generations of individuals seeking, discovering, and vindicating inalienable rights, rights no less real if suggestive of things spiritual. Such discovery, such formulation, such realization of natural rights look in retrospect like destiny.

Men today are not wholly lacking in this healthy sense of destiny if destiny be not defined as "arrival" in Who's Who but is known through this apprehension that life leads somewhere—if we give to it a more unreserved trust and thereby earn some sense of being led. Such a conviction is not merely a cultism or an awareness confined to the mystic. Any father who looks at his son in college during senior year and sees his lad become a significant person in his own right as he follows his own lead believes that his son has achieved just this inalienable right to participate in the great heritage of "enlightened freedom." Moreover, he may be convinced that his lad's birthright rests in something as inalienable and old-fashioned as to be called a soul and that this America should offer him a proving ground for this, his soul's inherent worth.

GROWING PAINS OF DEMOCRACY

Again, just as it is no accident that we are a nation under God, so it is not accidental but an integral and inseparable part of our natural growth that democratic processes should have been the solvent for repeated social upheavals in our national life. Democratic processes are but the social expression of that which is intrinsically individual and the "growing pains" by which a democracy must gain its maturity. On this score, how the mere word "socialism" frightened us fifteen years ago when even radicals in parlors were held suspect! Through our democratic processes, however, these turbulent spirits in our national life have been gradually as- similated and little scar tissue remains. In like fashion we feared communism, dreaded an epidemic which should spread its red rash in the body politic. Our healthy democratic processes, however, have held this menace at least in abeyance and in many quarters are winning it to a faith in a less material way out. On the other hand, we may well today regard class fascism in our country with healthy disfavor especially when it cloaks itself as a protector for the class which advocates it. Any oppression of the free spirit of man raises doubt as to the inherent and destined power of our tried democratic processes. "I am sure," said Washington in 1784, "if this country is preserved in tranquillity twenty years longer, it may bid defiance in a just cause to any power what- ever." Congress had less faith. It pushed through sedition laws, but it did so only to find the guiding genius of democracy— that inalienable right of every man to speak out of an enlightened freedom—was then, as it is now, the safest bulwark against this country's disintegration and overthrow.

The natural thing would be to see in this impulse for democracy a parallel to the aspiration of the human soul for God or to man's persistent quest for a spiritual authority, men being, as someone has said, incurably religious. But instead of regarding this impulse of the democratic processes as a parallel or analogy, suppose we think of it as just one more manifestation of what is genuinely spiritual. This feeling for enlightened freedom is more a matter of religious faith than some of us may admit. "Long may our land be bright with freedom's holy light," we may still sing during these present days when, in one more stage in man's history, church worship is often dull, and church religion may not be too sure of its God, and many grope wistfully for an authority which has some say with one's soul. It would be unsafe surely to identify the natural spirit of man with the Gocl in whom we trust, but we can safely believe that the human spirit is not expatriate in life and that it has an Ambassador at the Court of the Soul's Foreign Affairs. It may be that the democratic processes within the life of the nation are really the intended expression of those spiritual processes which are inherent in the soul of every man.

Here one ought not to attempt to make a case for religion, nor ought one to read into what is commonly called the secular that which is not there. Yet our natural heritage is basically a religious heritage. The religion of our land (whether it be the Christian religion or the Hebrew faith out of which the Christian religion sprung) is irrevocably identified with personality and the sanctity of the individual. Under no true interpretation of these religions can a man ever be anything other than an end in himself. Moreover, the human soul has attachments to a "beyond" whether it be conceived as an old-fashioned territorial heaven or as some world which takes off from the horizon of man's best qualitative attainment here. As such a being, he can never be subordinated to a State which arbitrarily governs him but must contribute his own sovereign powers of personality to a system of government which is the free choice of the governed. It is only thus that government can be under God. Such government expresses in its democratic processes the recognition of man's corporate spiritual instincts and upreachings, moulded and shaped by each man's admission of the inalienable spiritual welfare of the man beside him. This is not to put personality on a pedestal and to give it worship. It is to be biologically progressive and not retrograde. For the highest we know is the qualitative in man, and when he is regarded as a commodity in bulk to be packed and labeled for a state's consumption he has either sold his birthright or has had it fleeced from him.

One does not have to be technically religious to see that personality (the qualitative capacities of a person) appears to be life's ultimate aim. The reasoning which may lead to this conclusion is fairly familiar. Although no man has seen the Creator at any time, no intelligent person can fail to believe in the existence of God. The very "Mastery of the Mind's Desire," the restless pursuit of the elusive secret of the order and niceness, the balance and beauty of an enchanting universe reveals the creativeness of that which we creatures pursue. Further, a Creator implies a purpose. We rarely make anything without having some reason for it. Not long ago, however, I was pressing this point a trifle too vehemently to a group of lads in a preparatory school. One boy interrupted, "Not at all, sir, sometimes we just whittle." We came to a compromise in a conception of a God who may have enjoyed creating a universe for the sheer pleasure of making it, leaving it to us to be more soberly purposeful. It was George Saintsbury who said that some of us cannot conceive Apollo without the bent bow. The result of the Creator's pleasurable purpose is obviously people, while the most significant fact about people is the intangible qualitative something within them called personality. Finally, that which makes a person significant is his capacity to forget himself "for the sake of" something he holds of greater value and longer worth. A sound biological view of life must then have some perspective and philosophy in it and see the accruing values in the developing order of things. A supposedly intelligent outlook on life cannot surely see only a stack of catalogued recorded facts and no truth on the top of the pile. It would appear to a thoughtful observer as though the world must be worth something to the Creator. Now when man's developing spiritual processes lead him to the point where he can forget himself, he finds life and his world and the people of his country of worth in their own right and is bound to relate those inalienable rights to destiny and with the Creator's Supreme Desire.

Being finite, we human beings think of a Creator and a Finisher, of beginnings and endings. An infinite Creator, however, is not confined by Time. He makes us not only out of the materials which he has, but also out of the Spirit which he is, which is qualitative and timeless and, for the as- piring Christian, Christlike. As such, He is not less a Creator if He is better known to us as a Being of personal processes and identified with the spiritual impulse within our democratic processes, an Impulse and a Spirit of which we ever will be a part in our time and in His Eternity.

A DISTINCTIVE CAREER IN RELIGIOUS AND EDUCATIONAL WORK Donald Bradshaw Aldrich was graduated from Dartmouth in 1917, served in the Navy,and after the war attended the Episcopal Theological School in Cambridge, Mass. He wasassociated with the Cathedral Church of Saint Paul in Boston until 1925 when he wascalled to the Church of the Ascension on lower Fifth Avenue in New York City, a churchnoted for its liberal tradition and growing emphasis on community service in puttingreligion to work in practical terms. The honorary D.D. was conferred upon Mr. Aldrichby Dartmouth in 1927, and the Doctorate of Humane Letters by Kenyon College in 1935.He is a Charter Trustee of Princeton and a frequent speaker at eastern colleges.

DARTMOUTH DOCTORATE OF DIVINITY 1927

DONALD B. ALDRICH '17

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT HOPKINS TO BE IN HANOVER THIS TERM

November 1918 -

Article

ArticleCENTRAL STATES

December 1924 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

DECEMBER 1963 -

Article

ArticleMaster Builder

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

January 1941 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

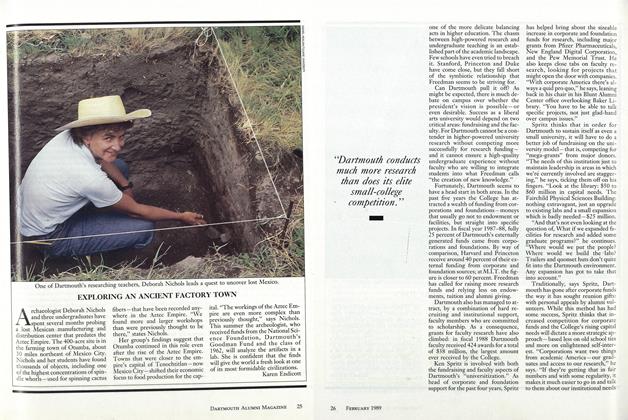

ArticleEXPLORING AN ANCIENT FACTORY TOWN

FEBRUARY 1989 By Karen Endicott