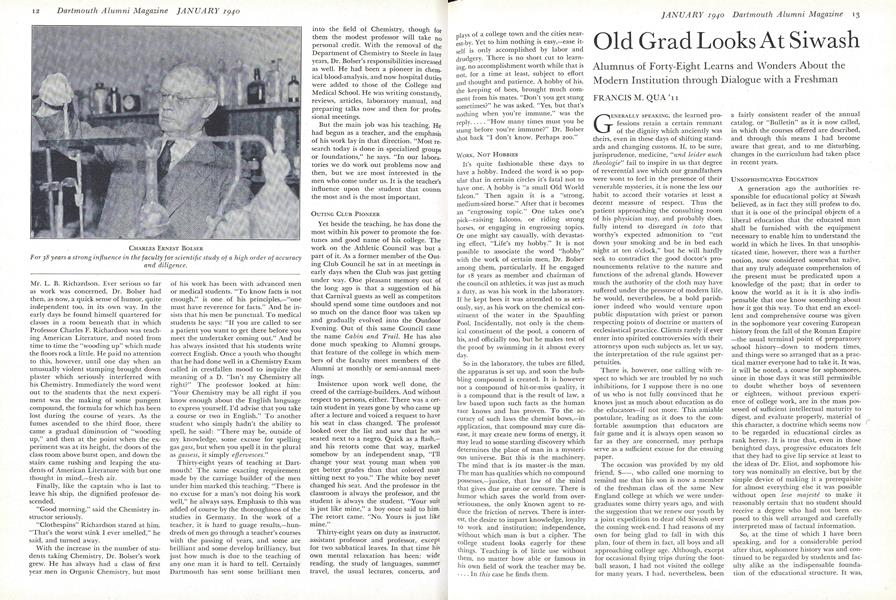

Alumnus of Forty-Eight Learns and Wonders About the Modern Institution through Dialogue with a Freshman

GENERALLY SPEAKING, the learned professions retain a certain remnant of the dignity which anciently was theirs, even in these days of shifting standards and changing customs. If, to be sure, jurisprudence, medicine, "und leider auchtheologie" fail to inspire in us that degree of reverential awe which our grandfathers were wont to feel in the presence of their venerable mysteries, it is none the less our habit to accord their votaries at least a decent measure of respect. Thus the patient approaching the consulting room of his physician may, and probably does, fully intend to disregard in toto that worthy's expected admonition to "cut down your smoking and be in bed each night at ten o'clock," but he will hardly seek to contradict the good doctor's pronouncements relative to the nature and functions of the adrenal glands. However much the authority of the cloth may have suffered under the pressure of modern life, he would, nevertheless, be a bold parishioner indeed who would venture upon public disputation with priest or parson respecting points of doctrine or matters of ecclesiastical practice. Clients rarely if ever enter into spirited controversies with their attorneys upon such subjects as, let us say, the interpretation of the rule against perpetuities.

There is, however, one calling with respect to which we are troubled by no such inhibitions, for I suppose there is no one of us who is not fully convinced that he knows just as much about education as do the educators—if not more. This amiable postulate, leading as it does to the comfortable assumption that educators are fair game and it is always open season so far as they are concerned, may perhaps serve as a sufficient excuse for the ensuing paper.

The occasion was provided by my old friend, S , who called one morning to remind me that his son is now a member of the freshman class of the same New England college at which we were undergraduates some thirty years ago, and with the suggestion that we renew our youth by a joint expedition to dear old Siwash over the coming week-end. I had reasons of my own for being glad to fall in with this plan, four of them in fact, all boys and all approaching college age. Although, except for occasional flying trips during the football season, I had not visited the college for many years, I had, nevertheless, been a fairly consistent reader of the annual catalog, or "Bulletin" as it is now called, in which the courses offered are described, and through this means I had become aware that great, and to me disturbing, changes in the curriculum had taken place in recent years.

UNSOPHISTICATED EDUCATION

A generation ago the authorities responsible for educational policy at Siwash believed, as in fact they still profess to do, that it is one of the principal objects of a liberal education that the educated man shall be furnished with the equipment necessary to enable him to understand the world in which he lives. In that unsophisticated time, however, there was a further notion, now considered somewhat nai've, that any truly adequate comprehension of the present must be predicated upon a knowledge of the past; that in order to know the world as it is it is also indispensable that one know something about how it got this way. To that end an excellent and comprehensive course was given in the sophomore year covering European history from the fall of the Roman Empire —the usual terminal point of preparatory school history—down to modern times, and things were so arranged that as a practical matter everyone had to take it. It was, it will be noted, a course for sophomores, since in those days it was still permissible to doubt whether boys of seventeen or eighteen, without previous experi ence of college work, are in the mass pos sessed of sufficient intellectual maturity to digest, and evaluate properly, material of this character, a doctrine which seems now to be regarded in educational circles as rank heresy. It is true that, even in those benighted days, progressive educators felt that they had to give lip service at least to the ideas of Dr. Eliot, and sophomore history was nominally an elective, but by the simple device of making it a prerequisite for almost everything else it was possible without open lese majeste to make it reasonably certain that no student should receive a degree who had not been exposed to this well arranged and carefully interpreted mass of factual information.

So, at the time o£ which I have been speaking, and for a considerable period after that, sophomore history was and continued to be regarded by students and faculty alike as the indispensable foundation of the educational structure. It was, therefore, with some inquietude that I had observed with the passing years that this basic course had first ceased to be a requirement for a degree and then been relegated to the background, where it appears to survive only in vestigial form as two single semester courses not required even of those students majoring in history, and that in the meantime a new foundation course had been developed, required of all freshmen—not sophomores, freshmen—and known as "Social Science 1 and 2." Such a label, however, is not exactly informative. What does it really mean? What, actually, forms the subject matter of this course which has been created to serve as the corner stone of the modern educational edifice, replacing that history which Lowell has called the "clarified experience" of mankind? What ends are sought, and through what means are they to be achieved?

In the issue of the "Bulletin" covering the academic year 1937-1938 we find the answers which the college itself has given to these very natural questions. It is there stated that the aims of "Social Science 1 and 2" are " (1) to create a lively interest in contemporary social, economic and political problems and the capacity to approach such problems from a critical and yet tolerant point of view; (2) to provide a wholesome respect for facts, a sense of time sequence and a common background of factual material for advanced work in the social sciences; (3) to emphasize the interrelations rather than the differences between the social sciences." Clearly, these announced objectives, in so far as they mean anything at all, are unexceptionable. They are in fact laudable. It looks, however, like a large order. Much would seem to depend upon the character and extent of the "factual material" to be presented from which this "wholesome re- spect for facts" is to be derived, on which this "time sequence" is to be based, out of which this "capacity to approach problems from a critical point of view" is to be developed. It is, therefore, distinctly disappointing to find no description of the content of the course other than the vague statement that it "will cover chiefly the period from the middle of the eighteenth century to the present, and will be primarily European in content, but relevant American material will be included wherever desirable and appropriate." It seems like a small investment from which to expect so rich a return.

A further perusal of this same issue of the "Bulletin" discloses other interesting things. It is, for example, at least surprising to find included in a list of ten individuals to be studied under the title "Representative Men of the Nineteenth Century," the names of Robespierre, Garibaldi, Marx, Tolstoy, and Lenin. Able men, yes. Interesting men, of course. But representative? Surely, not that. They were revolutionaries all—and they constitute five out of ten, a full half of the list. A similar lack of "critical capacity" on the part of someone in authority would seem to be indicated when it is observed that Benedict Arnold, John Brown, and Brigham Young are solemnly catalogued as "Representative Figures of Early American History." After these instances one is somewhat prepared for the discovery that, in the course on "Public Finance,"

"broader social and political aspects of the fiscal system are analyzed including the possibility of using the taxing power for non fiscal purposes such as the redistribution of wealth." The real gem of the collection, however, is the course entitled,

"Proposed Plans for Economic Reform," which is billed as, "A survey of the chief criticisms of our present economic organ- ization, with a careful analysis of the schemes and methods advanced to change this form of organization," and in which, "Emphasis is placed on a study of the Marxian analysis, the economic organization of Soviet Russia and of Fascist countries, and problems connected with economic planning."

OROZCO IRRITATES

Moreover, one one of my brief visits to the college I had seen the Orozco murals. I have no desire to add to the oceans of words which have been written about those celebrated pictures and I am wholly incompetent to discuss them from the point of view of art. In fact I may say that from that standpoint they rather appeal to me, particularly the panel showing the doughty conquistador, come to waste with fire and sword the presumably idyllic Aztec civilization. They are evidently the work of a highly intelligent man who is also a master craftsman. It seems equally obvious, however, that if there was ever such a thing in this world as unblushing social revolutionary propaganda in pictorial form those murals are it.

At this point it will, most likely, be ob- jected that neither one nor several swal- lows make a summer. That may be ad- mitted, but it is equally true that straws do show which way the wind blows. So on a recent Saturday as we drove, my friend and I, up into the glorious New Berkshire hills, there were questions in my mind, troubling questions which interfered to some extent with the pleasurable sense of homecoming induced by the familiar coun- tryside as we approached our destination, insistent questions which cried out for an answer.

To the returning graduate his first sight of the college, in its incomparable setting on the plain above the winding river, is a soul-satisfying experience compounded of a joyful recognition of old landmarks and a wholehearted admiration for the new. As things go in this country Siwash is old, and the development and expansion of its physical plant has been accomplished with a due respect for that age as well as a proper regard for present day requirements. The central green with its diagonal cross walks presents an appearance essentially unchanged for a century and more. The ancient buildings, entirely rebuilt and remodeled within, show not the slightest change in the simple and dignified exteriors so familiar to many generations of Siwash men. The new construction is wholly appropriate in architectural form as well as beautifully adapted to the uses for which it was designed. Also, mirabiledictu, the library is far more prominent and imposing than is the entirely adequate gymnasium.

In short, there is little if anything in the external aspect of the college which could afford even the most inveterate critic just cause for complaint. At first all this is re- assuring, inducing a sense of peace and of security in the presence of well remem- bered things. It is only later when one looks beneath the surface of brick and mortar seeking the intangibles, those things of the spirit which constitute the real college, that a doubt is reawakened.

That evening, in accordance with the immemorial custom of fathers and avuncular friends on such occasions, we had the boy at dinner with us in the Inn, plied him with food, and subjected him to merciless cross-examination. Young John, who aspires to be a doctor, is already pursuing studies of a pre-medical cast, and his talk at first was of organic and inorganic chemistry, qualitative analysis, biology and the like, matters in which I had no particular interest, although I noted that Sseemed well satisfied with the scientific progress which his son is making. My concern lay in other directions and when there came a pause in the talk I seized the opportunity to enter the conversation.

It should be explained, perhaps, that my young friend is an exceptionally in- telligent boy, eighteen years of age, who had an enviable preparatory school rec- ord, and whose interests are primarily scientific rather than cultural. I have known him ever since he was born and in talking with me he has always been free from any trace of self-consciousness, even the slightest. In order to preserve this ex- cellent relationship as well as to aid clarity of thought it is, as will be observed, our custom to employ the vernacular as a medium for the interchange of ideas. The dialogue which follows is actually a condensed and composite version of several talks we had then and later, but it is, I believe, a fair and accurate epitome of the important passages of each. Our conversation went something like this:

Me. John, what is this Social Philosophy or Social Science or whatever it is that you all have to take?

Freshman. Oh, that's great stuff. That's where they give you the real dope.

Me. What do you mean, the real dope? freshman. Why, the real low-down, like all that bunk about the Constitution, and all that.

Me. That's good. You mean what bunk it is to think that the Constitution is outmoded and that there is any necessity to amend or evade it in order to achieve progress?

freshman. Gosh, no! Just the other way 'round. I mean that bunk about the Constitution being a bulwark of liberty when it was really just written to protect their property.

Me. What do you mean? Freshman. Why, the Profs, say these men, after the Revolution got scared about their property and so, in 1787 I think it was, they got together and they wrote out the Constitution to protect it, and it has hampered us ever since.

Me. Thank heaven, it has had a tendency to hamper some people. The Constitution affords protection to the individual against encroachment by the government upon his rights.

Freshman. Ha, ha! You're a lawyer and you still believe that! The Profs, say that's just hooey to fool the people. The words seem to say that, but the real effect was to protect their property. That's why they wrote it down.

Me. You don't think, do you, that the principles embodied in the Constitution were invented in the Constitutional Convention of 1787? Freshman. Yeah, I guess so. 1787 I think it was. That's when they wrote it down.

Me. How about Magna Charta? How about the power of the purse, Hampden and the ship money? How about the Petition of Right, the Bill of Rights and the Revolution of 1688? Freshman. What were those?

Me. Don't you know that the provisions of the United States Constitution for the protection of civil liberties and individual rights are only the culmination of a series of bitter struggles of the English-speaking race throughout a full five hundred years? Freshman. No, I never heard that.

Me. All right. Let's drop the Constitution. What else do you get? Freshman. Well, the religious stuff is interesting, too. I mean comparative religions, how all religions contain the same bunk.

Me. Perhaps we'd better not talk about religion. I don't know anything about religion and I don't believe your Professors do either. The little that I know lies in the political and economic fields and you don't seem to know even that. How about economics?

Freshman. That's good, too. We learn how one per cent of the people in this country own ninety per cent of the wealth and exploit all the rest of the people through capitalism. Me. Oh, they do, do they?

Freshman. Yes. That's what Gauss says. Do you think that's right, that one per cent of the people rule all the rest? Me. No, I think it's a thumping lie. You ought to live in Lowell for a while. You'd at least change your mind about which one per cent it is.

Freshman. Well, Gauss says so; and that's why the government has got to step in and regulate everything so there'll be justice.

Me. How do they give this course? Is there a textbook?

Freshman. No. They start with the feudal system and come down to modern times and show how the industrialists got a strangle hold on the people throughMe. Yes, I know. Through capitalism. Freshman. Yes.

Me. But what I mean is, where do you get all this rot if there is no textbook? Is it through lectures?

Freshman. No. They give us things to read and then we discuss it and the Prof, leads the discussions.

Me. Well, whom do you read? Freshman. Well, there's Gauss and— Well, there's a lot of Gauss in it. We're reading about the Encyclopedists now, though. You know, the Encyclopedists were in France and—

Me. Yes, I've heard of them. But what do you get about the beginnings of thingseven before the feudal system? What do they tell you about the development of ideas, about monasticism and the rise of the Church, about the development of the arts and sciences and social organization, about the Rennaissance and the Reformation?

Freshman. We haven't had anything about those. As I understand it, the Profs, all got together and they decided that everything started with the feudal system and it isn't necessary to know about anything before that. That was when it started and then there was the rise of industrialism and so the industrialists

Me. Got a strangle hold on the people through capitalism. Freshman. Yes.

Me. All right. If you're so ignorant as not to know anything before feudalism I'll have to deal with you on that basis. What did you think of the condition of things under feudalism?

Freshman. I thought it was rotten. Me. Well, did it occur to you that that was precisely the time when the government regulated everything more closely than ever before or since?

Freshman. No. I never thought of that. But that was different. They were kings and nobles. They didn't do it for justice. Me. Government is government, power is power, and men are as they are. What reason is there to suppose that modern politicians would be any more just than the kings and nobles of those days? For example, which would you.rather be ruled by, a noble of the fourteenth century with a tradition of noblesse oblige, or Hitler? or even Mayor Hague of Jersey City? Freshman. But now they're going to do it for justice.

Me. I see. Well, let's take these Encyclopedists you say you're reading now. What do you think of them? Freshman. Oh, they were good guys. They saw the injustice of things and they wanted to take things apart and fix them up again right.

Me. But I seem to remember that they had a lot to say about natural rights and that it was too much regulation that they were kicking about. I should think you might call them rugged individualists. Freshman. Yeah, that's right too. But they were against injustice. If they were alive now I guess they'd be on the right side.

Me. But it was their ideas which prevailed. Do you mean to say that if they were alive now they would want to fight against the things they themselves stood for as exemplified in the modern democratic states?

Freshman. Yeah. They were in favor of justice. I think if they were here now they'd want to tear things apart and fix them over again. They seemed like that kind of guys.

Me. They did, indeed! One thing I can't understand is why these Professors who are themselves products of capitalism, who are maintained in their present positions by capitalism, and who owe their very opportunity to teach this kind of drivel to it, should be so eager to tear it down. Can't they see what has happened to their colleagues in those countries where the system has been abolished or radically modified?

Freshman. You don't get the idea. We're supposed to get convictions of our own. Convictions aren't any good if they're just the same ones your father has. They give us things to read on all sides of these questions and then we discuss them and make up our minds, and the Prof, doesn't say much at all. He just guides the discussions.

Me. All right. That sounds well enough. But let me ask you, whom have you been reading who defends capitalism? Freshman. W-e-1-1, nobody. But they say we don't need that. They say we'll hear that at home. Maybe it's hard to find any author who would be willing to defend capitalism. Gauss says—

Me. Who, in the name of all that's holy, is this Gauss you're always talking about? Freshman. What? Me. Who is Gauss? Freshman. You don't know Gauss?

Me. I never heard of Gauss in my life. Freshman. Gauss was—er, he was—well, the Profs, seem to think he was quite a fellow. I think he had something to do with Princeton. Do you know, this amuses me, kind of. You and my father, you're talking just like they said you would. They warned us about that. They said you were the unconscious tools of capitalism. Me. Look here, young fellow! I'm not the unconscious tool of capitalism. I'm a conscious tool of capitalism; and so is everyone else who isn't either a blithering ass or a Siwash Professor—or both.

Freshman. They said you'd get mad. Me. I'm not mad, I'm sorry; sorry for you poor devils who come here asking for bread and are being given stones.

Freshman. I think I've heard that before. Is it from Shakespeare? Me. My God! And you call yourself educated.

Freshman. No, I'm not educated yet, but I hope I will be if I stay here long enough. Me. Listen, boy! As near as I can find out, the longer you stay in this college the less

you'll know. Get back to your room and read some more Gauss. I'm going out and look at Copp's hill, with its rugged wooded flanks and its top covered with snow, and I'm going to reflect that Copp's hill was there before your Professors were born and, thank God, it'll still be there after they're all dead and gone to that lowest level of Hades justly reserved for the instructors of youth who have been faithless to their trust.

So I went out and stood on the green and looked across at the everlasting hills, and I wondered. I though of the things which had been taught on that spot to the young men of an earlier time, a time primitive even by the standards current in my own day—of a curriculum meager in content interpreted in an inadequate physical setting by men of narrow learning and in tolerant views. I thought, for example, of a President of the College who had believed and taught that it was ordained by God that the negro race should be held in bondage to the white—although careful to explain to a colored boy who happened to be in his class that his words had no personal application. I thought also of this, —that in the educational system of those days, however circumscribed in intellectual outlook it may have been, a place was always found for loyalty—loyalty to home and school, loyalty to country and the things for which it stood, loyalty to faith. And I thought of the men who went out from these hills after such trainingmen of courage, character and principle who, generation after generation, left their marks upon their section and upon the nation. Then I tried to think of some notable contributions made by the richer and more resplendent college of the present time but, rack my memory as I might, only two men came to mind graduated within the last quarter of a century whose reputation has been nation-wide and, of these, one is a moving picture producer and the other a New Deal tax expert. I wondered, and I wonder still.

I wonder how far the tendencies decried in this paper are peculiar to Siwash and how far they are characteristic of American higher education as a whole. As to that, my only sources of information have been the catalogs of eight or ten colleges and universities, large and small, supplemented by a half dozen articles and speeches of Presidents and Deans, and occasional casual conversations with such undergraduates here and there as I could for brief periods succeed in holding with my glittering eye. Based on such admittedly insufficient data, my suspicion is that the disease, if not epidemic, is at least pandemic, that it is the older and more prominent universities of the land which have proven most vulnerable to its onslaught, and that the attack at Siwash is one of the most virulent thus far observed.

SIWASH BOYS TOO YOUNG FOR THIS

I wonder if the academic authorities at Siwash have not, perhaps, fallen into the error frequently pointed out by President Hutchins of Chicago; that is, the mistake implicit in the attempt to apply methods reasonably suitable for European universities to American college freshmen who are, both culturally and absolutely in point of age, at least two and sometimes three years behind students abroad who are designated by the same term. If the colloquy with my young friend above reported be examined fairly and dispassionately it is, of course, possible to discern the existence of an idea underlying the methods pursued at Siwash in Social Science 1 and 2, an idea which might perhaps prove exceedingly valuable given a student body with the intellectual maturity and educational background of, for example, that of the Harvard Law School. The attempt, however, to apply such methods to the typical freshman with his active but unformed and essentially plastic mind discloses a failure to achieve ostensible objectives so abysmal as to appear little short of ludicrous. Instead of a "background of factual material," the unfortunate boy is actually left densely ignorant of the historical development of his race and nation; in place of "a capacity to approach social, economic and political problems from a critical and yet tolerant point of view," he is in fact supplied with a ready-made, wholly uncritical and most intolerant belief that the radical and revolutionary ideology is somehow allied With justice in a holy war against all he has previously known which, it now appears, is either actually malevolent or, if not that, is at least ignorant and stupid. In short the boy, coming from a sheltered environment and wholly without experience, is suddenly deprived of all the faith and all the beliefs which have hitherto been the basis of his character and the mainspring of his conduct, and nothing solid or substantial is given him to take their places. Moreover, the fact that the chan nels into which his thoughts are led appear to tend exclusively to the left is sufficient to arouse a suspicion that perhaps the objectives as announced do not constitute a full and frank exposition of the purposes which his preceptors actually have in mind.

I wonder about academic freedom. "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it." These are ringing words which evoke a responsive chord in all our hearts, but I wonder if there are not certain reasonable regulations as to place where and time when which should be observed even in the matter of academic free speech. If a man wishes to believe that two and two make five, that is undoubtedly his privilege. More, if such a one be moved by the spirit to tell the world that two and two make five, he should have that right as well. Otherwise, if any authority were to be established with the power to prevent the exposition of his views there could, obviously, never be any assurance that that authority might not suppress some other prophet with a message more worthwhile. Does it, however, necessarily follow that such an unorthodox calculator must be permitted to proclaim his thesis from the presumably authoritative rostrum of a lecture hall at, let us say, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to students who are shortly going forth to build the bridges over which we must pass and the buildings in which we must live and work?

I did wonder why on earth anyone of reasonable intelligence and having to his credit the scholastic attainments presum- ably required of members of our college faculties should wish to teach bizarre and extravagant doctrines which are con- demned by the overwhelming majority of mature and educated men, but a little re- flection has convinced me that this curious tendency on the part of our younger Pro- fessors may be quite easily explained on the basis of well understood and frequently encountered psychological phenomena. There is nothing exciting or particularly inspiring in the contemplation of the career of old Professor Twiddlededee who has gone through life patiently and soberly teaching successive generations of students that two and two make four, until now he is old and grey-headed and about to retire without any special notice having been taken of him, without ever having been so much as the center of a controversy. Contrast with this the position of young Professor Umpdedunk who, early in his term of service, has published a ringing monograph to the effect that the world has too long been the victim of a false and outmoded system of numerology and that most human ills are in fact the result of a blind and uncritical acceptance on the part of many generations of men of the wholly baseless assumption that two and two make four, whereas a reexamination of the problem from a fresh angle of approach with a of the fundamental factors involved in the light of newly discovered principles of transcendental relativity demonstrates conclusively that actually two and two do and always did make five.

At once young Professor Umpdedunk is the center of attention. The academic spotlight is turned in his direction. Books are written attacking and defending his theories which, in order to enhance their importance, are always referred to as "concepts." Students are attracted to his classes and his monograph is expanded into a course of lectures. It appears that the matter has a moral aspect. If two dollars and two dollars really make five dollars will not the poor be benefited? Obviously. If two dollars and two dollars always did make five dollars who, through the ages, have been the beneficiaries of the extra dollars? Who but the selfish few who have invented and perpetuated the orthodox doctrine for the sinister purpose of exploiting the masses of their fellow men? Umpdedunk's movement becomes a crusade. To the stature of an intellectual giant is added the halo of a saint. He is sought after by women's clubs for afternoon lectures. His soul is warmed by adulation. His thesis is ready made for the politician and the demagogue. He is even called by government to sit in the seat of the mighty.

It is not wonderful that such men are to be found. Considered as phenomena they are by no means unprecedented. Some of my readers will doubtless remem- ber one or two professorial meteors of the sort which flashed across the academic skies a generation and more ago. In those days, however, such a one was a meteor only. Came the day when the places which had reflected his brief effulgence knew him no more and the academic shades, confused for a moment in the paralyzing glare, were permitted to resume their wonted reflective calm. The wonder lies in the fact that such men now become comets with fixed orbits and tails com- posed of young instructors imitating in their feebler way the glories of the master. I wonder. I wonder if the colleges still feel that their primary purpose is the training of young men, or if the Siwash of today is, rather, operated for the aggrandizement of young Professor Umpdedunk.

With this thought we are brought squarely up against a fundamental question. What should be the nature and object of the American college? Should it be primarily a place where scholars may gather to pursue their work of research into and speculation upon the problems of all sorts, physical, moral and social, which confront the human race, and to which mature students may resort to examine the results of their labors, accepting what seems to them good, and rejecting those portions which they may consider unsound? Should it, in other words, approach more and more closely the ideal of the European university? Or should it resolutely turn its back upon these no doubt attractive kingdoms of the world and reassume its traditional role in the national life by devoting its energies and wealth to the training of the immature youth of the nation in character and in the use of their intellectual faculties, while providing them at the same time with that broad, solid basis of non-controversial fact which they will so sorely need, whether they are to pursue a further course of study with that "critical capacity" which, it seems to be agreed on all sides, is eminently to be desired, or are merely to live in the world as it is?

To me, at least, it would seem that to ask these questions is to answer them as well. We have in our educational system nothing closely resembling the lycees and colleges of France, the gymnasia of the old Germany, or the public schools of England. Educators may talk of the functions of the "junior college" but, broadly speaking, there are as yet no junior colleges to do the job which must be done. If our children cannot look to the colleges to do for them what they have done for so many generations of their predecessors, where then shall they turn? Surely, their need is great. The times in which we live call as never before for men, not leaders only but followers as well, whose judgment shall be sound, whose aims shall be at once practical and idealistic, and whose courage shall be adequate to meet the tests which even now loom out of the mists ahead. If we are to have such men youth must have guidance, and it must be a guidance not destructive but constructive, animated not by cynicism but by faith.

The other day, having expressed some of the notions—or should I say "concepts"? —which are set forth in this paper to a friend who prides himself upon the modernity of his outlook, I was met, surprisingly enough, by a quotation from the Bible, "Say not thou, What is the cause that the former days were better than these? for thou dost not enquire wisely concerning this." Kindly, he went on to explain, "The trouble with you is that, while you are in fact only forty-eight years old, you are equipped with a set of fundamental ideas which could not possibly be appropriate to a man a day less than eighty-four." Well, if so, so be it. But I wonder. I wonder if the educators of today are not in danger of forgetting another Biblical admonition which seems almost to have been composed for their especial benefit, a verse engraved long ago in monumental letters high above the portal of a building at our oldest university, "Thou shalt teach them ordinances and laws, and shalt shew them the way wherein they must walk, and the work that they must do."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

January 1940 -

Article

ArticleExacting Requirements in Science

January 1940 By ERIC P. KELLY '06 -

Article

ArticleThe College In The Sixties

January 1940 By DR. WILLIAM LELAND HOLT -

Article

ArticleCameos of a Crisis

January 1940 By ALAN L. STROUT '18 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

January 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

January 1940 By ERNEST H. EARLEY