Professor L. B. Richardson '00, Teacher, Chemist, Historian, Is a Liberal College in Himself

FOR PROFESSOR L. B. RICHARDSON, if a college is to live it must continually advance through the activities of those who serve its fundamental aims with sympathy, intelligence, and vigor. That concept must have motivated his own varied activities ever since he unexpectedly met his first class nearly forty years ago. Certainly in those years few men of Dartmouth can have rendered more significant services to the College on the Hill.

The only person likely to disagree with such a statement is Professor Richardson himself. The man has absolutely no idea what his character is really like, or what his indefatigable activity has meant, or how fully he exemplifies what liberal education at its best implies. After one of his recent lectures, an undergraduate quite simply said, "He's great." Professor Richardson didn't hear his student; but if he had, he wouldn't have understood. In such notions of himself as he has ever taken time to have, he pays not the slightest heed to his lifelong insistence on the importance of facts in arriving at conclusions and cherishes a fantasy as full of incongruities as Mark Twain's wildest flights.

To the amusement of his friends, he has intimated now and then, with all the seriousness he usually reserves for work, that as a chemist he's a misfit, that as a teacher he only talks, that the report of the undergraduate committee on the revision of the curriculum was as influential as his own, that his special studies have been unproductive, that his administrative activities have been routine, and that he's really a Caspar Milquetoast only interested in quiet.

In that whole picture, "quiet" is of course the only word of truth. Leon Burr Richardson has always been, as self-contained as his Yankee ancestors who helped to settle and develop Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Like them, too, he has always had incredible vitality, a vigorous and independent mind, a shrewd sense of values, an innate respect for learning, a homespun recognition of hard work as a condition of existence, an impatience with the careless and the shoddy, and behind an inherited reserve a warm friendliness and a rich sense of humor.

As a chemist, he has persistently kept abreast of developments in his special field during a period when new theories have been continually replacing old; and until his abilities and interests led him into other spheres as well, he was carrying on studies (he characteristically dislikes the pretentious connotations graduate schools have given to the term "research") in the adsorption of gases, and occasionally publishing a paper when he was fully satisfied that he had information of real value to present.

At the same time, he was forever busy with his teaching as a full-time job, often giving several courses, sometimes superintending laboratory work besides, and always developing his lecturing into a finely calculated art that makes his classes exciting illustrations of what the scientific method means, of what any quest for understanding based on knowledge necessarily exacts, and of the pleasure such intellectual activity affords.

AUTHORITY ON EDUCATION

Meanwhile, he was for years working with the Committee on Admission in the selection of the students Dartmouth was to have, he was helping to institute the policy of rotating chairmen of departments that now prevails, and he was quietly demanding a new building for his own department, studying laboratory planning, and finally to a considerable extent directing the interior design of Steele Chemistry Building in 1921.

Soon after that, as chairman of the Committee on Educational Policy, he got going with A Study of the Liberal College, for which he spent seven months visiting colleges and universities in the United States, Canada, and Great Britain. That study, when it appeared in 1924, not only revolutionized the curriculum at Dartmouth but also provoked such widespread discussion among educators in both America and Europe that the Association of American) Universities had him address a conference, Columbia had him lecture to summer session classes of college presidents and deans, a leading university became anxious to have him fill an administrative office, and institutions throughout the world have been asking Dartmouth to send them copies ever since.

On the strength of that book, Professor Richardson, like many another successful author, could have spent the rest of his life reinterpreting the ideas he'd advanced. Instead, he wrote a now widely used General Chemistry which presents more of the history of the science than any other sold, and probably more about its relation to other fields of knowledge and to everyday affairs. But that was done by 1927, and a revision wasn't likely to be necessary for several years. In the interim, at the request of President Hopkins and with the support of the trustees, he wrote a new History of Dartmouth College (1932) from source materials including many documents hitherto unused and some unknown, among the last being 10,000 letters. One authority has called those two solid volumes the most readable and interesting college history ever written. Another says they are the only college history in which no error has been found, but Professor Richardson insists that isn't true—he knows he made an error of one year in the class of a man who graduated in the early nineties, just before his time. At any rate, as the four years he spent on the history familiarized him with the archives, he next turned to editing letters and diaries concerned with Samson Occom's and Nathaniel Whitaker's mission to collect funds which enabled Eleazar Wheelock to found Dartmouth. His hand now being in, the three hundred seventy-six pages of that volume, An Indian Preacher in England, only occupied him for a year; and after its publication in 1933, he took what he probably thought of as a rest for about another. But by 1935, he was devoting his spare time, including all vacations, to studying the neglected and misinterpreted career of William Eaton Chandler, an eminent figure in the Gilded Age, to whom he felt it was about time someone rendered justice.

In that opinion, as in so many others, he seems to have been entirely right. William Eaton Chandler, after studying law at Harvard and learning politics in Concord, New Hampshire, helped to secure Lincoln's renomination in 1864, went to Washington to prosecute fraud in the Philadelphia Navy Yard, was appointed Assistant Secretary of the Treasury by Johnson but resigned to be a lobbyist, became secretary of the Republican National Committee and managed the campaigns of 1868 and 1872 for Grant, is credited with having secured the election of 1876 for Hayes, was appointed Solicitor-General by Garfield, started the building of a steel navy as Secretary of the Navy under Arthur, became an influential Senator from New Hampshire for fourteen years, and fought the railroads in his state singlehanded for twenty-five. Meanwhile, he had bought the Concord Monitor and weekly Independent Statesman, in both of which as in his private writings he commented on all significant political and social questions of the time. When he died, he left some 80,000 private papers, half of which are now in the Library of Congress and half in the New Hampshire Historical Society's collection in Concord, and all of which Professor Richardson has read. Such investigation, together with exhaustive study of the period, has confirmed his impression that Chandler, though a shrewd politician, was not the unscrupulous rascal commonly supposed but instead a vital fighter who was generally on the right side and who sometimes could be called our first progressive.

Writing his recently completed biography of Chandler, he says, gave him a good time and kept him out of mischief for four years. Last summer one of America's leading historians read the 400,000 word manuscript enthusiastically; but Professor Richardson, still unsatisfied, spent the next five months cutting it in half. Always independent, he has refused offers of subsidized publication, insisting that if his book has any value it should find a market.

To keep most men—but not him—out of mischief, the activities enumerated would seem enough. The man's capacity for vitally effective work is scarcely credible: one could fill a column with what he has done—and not recorded. Briefly, among much else besides his teaching, he has constantly assisted President Hopkins during the last decade and more of change; he is secretary of the class of 1900 and a hard-working member of the Alumni Fund Committee of the Alumni Council; he has been such a popular speaker—always on the aims, practices, and problems of the College as an institution of learning—at alumni clubs throughout the east and middle west that those fortunate enough to hear him have kept him answering questions far into the night and then often carried him off to what he calls "all sorts of places"; he has been chairman of the chemistry department; he long attended many meetings of chemical societies and has been president of the New Hampshire Academy of Sciences; he . has been active as a member of the council of the American Association of University Professors, president of the Dartmouth chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, and a member of the Hanover Board of Education; and he has found time to bring up three lively sons and to pursue all sorts of other interests.

He has never played golf or bridge and never wants to. He never watches undergraduate athletics and thinks football is "the dullest game going," an opinion to which he's entitled since he can tell you more about it than he'll admit. He says the radio mostly offers "stuff beneath contempt" and is a "beautiful example of how scientists develop undreamed of machines that are so used as not to be any good." He dislikes cities; all singing—including opera; and the preoccupation of recent novelists with history—as in GoneWith the Wind, which he thinks prejudiced, and with the sordid—as in TheGrapes of Wrath, which he thinks is lacking in the beauty of form into which great artists shape even the ugliest materials. He doesn't care for the Orozco frescoes. He hates all games except tennis, which he used to enjoy "playing at," and professional baseball, which he has always loved to watch and about which he can answer anything you ask. Swing "grates on his nerves," producing an effect wonderful to watch.

He enjoys the country and the seathough like the Yankee that he is he wouldn't ever say so. He used to be seen walking in the hills, sometimes even on Moosilauke, and he now likes to drive through the Connecticut valley in his Oldsmobile, which he keeps in an unheated garage. The same taste for the outdoors makes him fond of ocean voyages, though he has only allowed himself two trips to Europe, and of motorboating—especially when it's rough—off Cape Cod, where in the summer he sometimes visits friends.

TASTE OF A CONNOISSEUR

He enjoys "a fine orchestra playing something composed before 1900"; the paintings of old masters and Grant Wood; hopefully going to the movies about every other week in quest of "something worth while," which he doesn't often find, or "something funny," which he doesn't find as often as he'd like; and above all reading from a sheer delight in books.

This teacher has the insatiable desire to read that all should have but only some are born with. Since childhood, he has always read voraciously in whatever caught his interest; and since he entered college, in French as well as English, using his German only for his science. He has never cared about philosophy or literary criticism; and he will tell you he has never cared for poetry—if an old friend isn't in the room. He used to read much fiction, of which he remembers with particular delight Jane Austen, Dickens, Thackeray, and Mark Twain whom in some ways he resembles; and he would still read good novels if he thought they were being written. Since he doesn't, for relaxation he reads detective stories, though they can't offer much as he solves them as quickly as he does cross-word puzzles. He reads everything in the daily paper, including the funnies and the sporting section; and he is always fully posted on current events. At different times, his boundless curiosity has led him to read widely about Gothic architecture, art, ants, and a hundred other subjects. But now he chiefly reads history, biography, economics, sociology, and memoirs in which the seemingly inconsequential doings of forgotten people reveal what life was actually like in former times. For such work, his appetite has always been insatiable, his taste that of a connoisseur, and his perceptions incessantly alive, with the result that his fund of information about local, American, and European history is encyclopedic but precise.

That knowledge, coupled with his New England heritage, causes him, in thoughtful moments, to be appalled by what modern man has made of life. He won't talk about the war: "What is there to say?" He isn't a New Dealer, but he is "ardently against the old" and thinks "all criticism brought against the New Deal is without point because the critics have nothing to advance instead." He thinks that the profit system is nearly bankrupt and that it has got to expand so as to employ everyone who wants to work or else support those who can't get jobs; and that if it doesn't do either, it is ethically wrong and its supporters have no right to kick about hard times. He would like to see a system of nationalized production eventually developed, and he would be a socialist if he could "readily conceive of men honest and able enough to work out the enormous problems of management involved." As a matter of fact, he is registered as a Republican, though he has voted for "all sorts of people," always supporting men or policies, not parties. In his politics, as in his work for the College, L. B. Richardson has been an independent preeminently concerned with the common good.

Unfortunately for the credit that might otherwise accrue to Dartmouth, the making of this man began long before he entered college—probably as far back as 1632. In that year, the Richardsons and Burrs (his maternal ancestors) both came out from England to the wilderness of Massachusetts, where the Richardsons settled near Woburn and the Burrs soon joined the original migration to Connecticut. Neither family was the kind likely to stay put. By the early eighteenth century, the Richardsons were moving northwest to Pelham, New Hampshire; and by the seven teen-eighties, on again to Cornish, a few miles from where Wheelock had recently arrived with his Bible and his drum. About the same time, the Burrs, after having been active in Connecticut affairs, moved up the river to Thet ford, Vermont, about as far north of Hanover as the Richardsons were south. But in spite of such proximity to Dartmouth, neither family was to send a son there until they intermarried.

Professor Richardson's forbears were mostly God-fearing, hard-working, tenacious farmers who got the hill winds in their veins without benefit of college. His father—Orlando Joseph Richardson—was a skilled carpenter and machinist who moved to Lebanon to practice his craft. There Leon Burr Richardson was born (April 14, 1878) and grew up.

The Lebanon of his childhood still had an old-fashioned village atmosphere, and its inhabitants themselves created such activities and recreations as they had without the help of organizations, business or social. For the children, there was the kind of schooling under which they were expected to assimilate specific knowledge; there were regular chores which gave them a healthy respect for effective work; and there were such pastimes as they could invent, which gave them a feeling for the countryside and a sturdy self-reliance. Professor Richardson thinks most twentieth century alumni would have found the conditions of his boyhood hard, but he had fun and throve. At the same time, he read habitually in whatever came to hand; and as his father was a zealous Baptist and an old-line Republican, he had solid standards against which to revolt when forming his own. So his mind developed with his body; and by the time he got to high school, he was ready to appreciate some of the best teaching he has ever known.

Robert Forsyth—the principal and one of the three teachers who comprised the school's whole staff—was the kind of lonely and influential figure that used to be familiar in small towns. His high standards and his meagre pay made him something of a martinet; his devotion to the subjects that he taught and his lack of intellectual companionship made him somewhat narrow; and in his teaching he probably violated all the precepts now insisted on in courses in education. But he was a scholar who demanded of his pupils the same ideal of thoroughness and exactness that he pursued himself. On those who came before him, he exerted a quiet, unassertive, and persistent influence. Young Leon Richardson studied Latin and mathematics with Robert Forsyth and carried away a sense of what devotion to learning for its own sake means. Besides that, his studies in the Lebanon high school gave him an ability to read French, which he has exercised ever since, and an interest in history, which was deadened for a decade by the way he found it taught in college.

When he entered Dartmouth with the class of 1900, the change in which he was eventually to play so great a part was alr eady setting in as everyone unconsciously partook of President Tucker's wisdom, foresight, and nobility of soul. The curriculum was expanding and the faculty, he enthusiastically remembers, included such great teachers as Professors Edwin J. Bartlett (chemistry), Frank H. Dixon (economics), John K. Lord (Latin), Charles F. Richardson (English), and David C. Wells (sociology). Although the library was housed in Wilson, the chemistry department on the first floor of Culver, and the gymnasium in Bissell, the buff walls of Butterfield, since torn down to make way for Baker, seemed the height of,modernity and heralded an era of construction. The undergraduates still numbered only a few hundred and still came mostly from New Hampshire; but the enrollment was increasing annually, about half the students were expecting to enter business, and interest in extra-curricular activity was for many overshadowing that in books. Especially football had already captured the undergraduate imagination, though Dartmouth's big games were still with Amherst and Williams, and when the team had a bad season it had to raise money to meet the deficit before it could play the next, which was all right with L. B. Richardson.

In college he "made many friends and had a fine time"; but he never engaged in any extra-curricular activity, a fact of which he is proud, and he never competed for prizes, though he had almost no money. He roomed under the clock on the third floor of old Dartmouth Hall, which rocked in the wind like a ship in a storm. He heated his room with a stove for which he pulled coal up himself. He often ate on considerably less than three dollars a week. He met his tuition with scholarships awarded on a basis of grades. He explored new horizons revealed to him by no-one knows how many of the 75,000 volumes in Wilson. And in his studies, he was forever trying to seek out knowledge for himself. In history, though he disliked the way it was taught, he wrote brilliant papers on the secession of Connecticut river towns from New Hampshire to Vermont during the Revolution, a study he would take up again when writing his History of Dartmouth College. In geology, he amazed his professor by learning everything there was to know about a fossil bird called archaeopteryx because his curiosity had been aroused by its name. In economics, while writing a paper on the Credit Mobilier, he discovered in the library a magazine article that Senator James W. Patterson '48, a former Dartmouth professor, had inadvertently so annotated as to implicate himself to a greater extent than he had been willing to admit, a matter to which Professor Richardson has returned in his biography of William Eaton Chandler. His interest in chemistry, then a relatively new subject in colleges, developed in his junior year, when he elected it as a fifth course to fill out his schedule. Thereafter he gave all his time to it, doing so well that on graduation he was offered a laboratory assistant ship, which was really a graduate fellowship approved by the whole faculty. The future professor had no money or plans, and he was fascinated by the subject; so he accepted.

About a year and a half later, he unexpectedly began to teach, at the same time acquiring the inappropriate nickname that ever since has been misunderstood. The chemistry department then consisted of Professor Bartlett, Dr. (now Professor) Bolser, who had just joined the staff, and one Dr. C. H. Richardson. That Dr. Richardson was known about the campus as "the cheerful idiot," apparently not without some justification: among other things, when undergraduates staged in Norwich the by then petrified hoax of the petrified man, "the cheerful idiot" excitedly discussed the human characteristics of a lump of concrete. At all events, in the middle of the academic year 1901-2, Dr. C. H. Richardson transferred to another department and Mr. L. B. Richardson was given the promising job of introducing order into his classes and some knowledge of chemistry into his students' heads. In the process, the new instructor, for all his keen mind and ready wit, was misnamed "cheerless," partly from the contrast to his predecessor, partly from his imperturbability; and the unjust nickname, like so many perversely applied by students, stuck.

Dartmouth undergraduates were then notorious as the most disorderly in the United States unless an instructor won their complete respect. Professor Richardson says he used to dream his students were throwing him out the classroom window, but he can't have been haunted by such dreams for long, as he struck his characteristic manner at the first. To impress the unruly, he planned to make a memorable noise when illustrating the explosiveness of chlorine dioxide. So he used a ten-inch test tube and to his own amazement got no noise at all. With seeming unconcern, he then went right on talking and, hoping for results, casually held the test tube in a flame, which produced an explosion like that of a twelve-inch gun. The blast deafened him for most of the remainder of the hour, but he talked quietly on just as if it had been intended, and at the end three awed youths stopped to say that he had given the finest performance of any kind they had ever seen. He has not» tried that particular experiment again, but many of his students are still saying the same thing.

The course with which he began his teaching was ostensibly the same one he now gives—General Inorganic Chemistry; but through the years its subject matter has changed so much that today he is presenting almost nothing he did then. Moreover, no two of his lectures on the same topic—even to successive sections of the two hundred and more students he now has—have ever been the same, as he has always gone to each class in a spirit of adventure and adapted whatever he has had to say to the students present. He can't understand teachers who feel that they go stale, for to him each class is a meeting of interesting individuals who require a fresh approach. At times, like every teacher, he has come out of class, for all his brilliance, feeling "like a poor stick who should never have been allowed to teach." But his students—except the kind who try to go to classes unprepared and to engage in speculation without knowledge—have always come out feeling that chemistry is an exciting subject, that the pursuit of understanding requires disciplined thought, and that the meaning of a liberal education has been revealed to them by the erect and brisk but genially helpful gentleman with scrutinizing eyes and a beaming smile who has put his richly informed and stimulating mind completely at their service.

His CLASSROOM

Although each section of his course numbers fifty to sixty students, he lectures without notes and creates the atmosphere of a small discussion group. He takes the roll himself and knows each man by name. He is so steeped in his subject that he can present the topic of the hour in whatever form seems best. He speaks simply, clearly, and precisely. He never has to pause to find the word he wants. His talk flows easily with unpremeditated art. He explains, interprets, illustrates with lucid diagrams and deft experiments, questions both the class and individuals, and intermittently moves forward from his desk to discuss inquiries. Yet the rhythm of his lecture, which is that of his own thought and talk, is never for a moment broken; and throughout the hour the central topic is beautifully pointed up and rounded out.

In return he expects and gets complete attention. His students arrive early, hasten to their seats, quickly open texts and notebooks, quietly talk over whatever they don't understand, and then become completely silent as soon as he appears. He tells them: "We can teach people sometimes if they don't think they know it already, but we can't teach them anything if they do. The tendency to cling to error is the greatest tendency of the human mind, and in science the simple explanation is almost never right. Definitions, although well enough in themselves, are of slight avail when learned with little real understanding and repeated with the glib fluency of the phonograph. Let us therefore define the definitions." Such informed understanding, his students must incessantly pursue, first studying their text, then attending lectures for further illustration and interpretation and sometimes for correction, and then mulling over both text and lectures at leisure.

If those who take his course, which is designed as an introduction to college work in chemistry, acquire some understanding of the nature and the value of the scientific method, of the significance of chemistry for modern man, and of the meaning and relationship of the facts and theories studied, he thinks their time and his have been well spent. The facts, formulas, and theories which they learn are tools. Memorization by itself never enables them to pass. They must show understanding. They must be able to perceive relationships and to apply their knowledge. In the exercises in his GeneralChemistry, for example, there are not only questions of the more usual kind but also such others as: What relation has chemistry to the study of, let us say, economics? Why is a cooling effect produced by sprinkling the floor with water? What may have induced the early settlers in Virginia to select the glass industry as the first one to introduce? Under what circumstances is it desirable to reduce the sugar content of the diet? Why is it probable that water does not exist on the sun? Have we convincing proof of the existence of ions?

The wealth of information Professor L. B. Richardson imparts is the product of intensive study carried on for years, almost entirely on his own and always out of an instinctive love of learning. After taking his master's degree at Dartmouth (1902), he studied for a year (1904-5) at the University of Pennsylvania, only to be disgusted with the kind of work required in graduate schools. To him, "the garb of the scholar is something terrible, the method of the scholar is something awful, and the trappings on the Ph. D. do an infinite amount of harm." So he came back to Hanover without one, married, and waited for his assistant professorship until 1910 and for his full professorship until 1919. Meanwhile, to the benefit of all concerned, including such students as Professor Scarlett 'lO and Roswell Magill '16, he was one of those teachers who, as he has memorably said of others, "instead of devoting themselves to Research with a large R modestly content themselves with study—with a small s: study, some of which has to do with effective presentation of material to their classes." That idea is basic in his concept of the function of the teacher in the liberal college.

The fundamental purpose of the liberal college, he believes, is the intellectual development of the student. In writing of the objective which he feels has been Dartmouth's from the first, he has observed: "What Wheelock had in mind was to arouse in those under his charge a respect for human knowledge, so far as the domain of human knowledge can extend, to inspire in them an intellectual curiosity wide in its range, to animate in them a spirit which would impel them to devote their talents and their acquirements to the service of their fellow men. Such is the aim of the College today." Elsewhere he has said that in the last analysis the fulfillment of that purpose depends upon the student himself.

Consequently he regards much extracurricular activity somewhat querulously. In particular, he thinks the present system of intercollegiate athletics—especially football—grew up insidiously and "can't be defended on any basis connected with an educational institution." He thinks the greatest advantage of such athletics is that students who participate acquire an ability to take hard knocks and thereby become more maturely self-reliant. But he thinks varsity football demands an absurd amount of a student's time, and no-one who can't furnish proof of being supported solely by his immediate family should be allowed to play. Fundamentally, what he dislikes is organized activity of any kind. He thinks all students should play only what and when they like without being watched by anybody. That to him is "the only kind of athletic activity worth a hoot."

The tendency intermittently apparent among some undergraduates to exalt pleasant companionship, extra-curricular activity, and so-called progressive education seems to him to challenge the very existence of the liberal college. He thinks that in recent years Dartmouth has been continually enrolling more students of the kind it needs, but that many of them, having been sheltered all their lives, have been lacking in the mental stamina essential for the most productive study. He finds more intelligence and aptitude among his students now than in the past—except for the twenties, when he thinks they were more promising and lively; but he wishes more undergraduates had more appreciation of the value of hard work. He thinks they often tend to get too little knowledge of too much, and he would prefer to have them take fewer courses and work more intensively in each. He doesn't believe that intellectual interests can be' consciously aroused; he disapproves of courses intended for that purpose; and he spends a fair share of his own time discouraging young men who in secondary school, though lacking the innate ability required, decided to be chemists. Similarly, he dislikes popularized surveys, which he feels "often make a student think he's getting somewhere when he isn't and at best give him only such knowledge as he could get without the help of any teacher by reading for himself." He thinks one of the duties of the College at the present time is to overcome the effects of progressive education , which he says "ought to be applied to athletics, where it would work out beautifully."

Sometimes he wonders whether the liberal college can indefinitely endure if more and more students use it for purposes for which it does not primarily exist. Then he remembers alumni who were poor students or even play-boys twenty to forty years ago but who as a result of their years at Dartmouth have developed intellectually since. Middleaged alumni, he insists, afford the only basis for judging the extent to which the College has been realizing its fundamental aim; but more men should be graduating with more effectively developed minds, liver intellectual interests, and broader points of view.

That challenge, he believes, teachers in the liberal college must now meet, not only in the interest of maintaining a high academic standard but also in fulfillment of their duty to society. He thinks the general level of instruction throughout the College is probably higher than it has ever been before; and for the work of many younger men, he has only praise; but he feels that the training to which graduate schools subject most future teachers is inimical to liberal education. He thinks that every teacher should constantly study his special field and its relationships to others but that lots of good teachers are deadened by what graduate schools have made of research. The liberal college, he believes, now most needs teachers of the kind who helped to give him his enthusiasm for learning half a century ago—men who, without being less exacting, have an infectiously vital interest in their subject and its bearings upon others that uncon- sciously enlarges the intellectual horizons of their students and stimulates emulation. Under such teachers, as Professor L. B. Richardson is fond of saying, students unwittingly grow alive to the value and the pleasure of intellectual activity, thereby becoming better companions to themselves and more useful members of society; and with such teachers on the faculty, the liberal college can leave the future to itself.

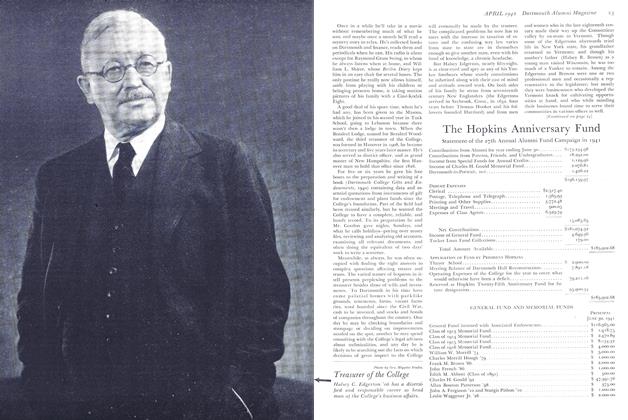

A LECTURE IN 106 STEELE, FAMILIAR TO SOME TWO HUNDRED STUDENTS EVERY SEMESTER IN L. B. RICHARDSON'S CHEMISTRY 3-4

ARTHUR DEWING '25 English teacher who is author of the biographical profile of Prof. L. B. RichardsonClass of 'OO in this issue.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

March 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticleAn Obligation to Alumni

March 1940 By BEN AMES WILLIAMS '10 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

March 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

March 1940 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Article

ArticleThe College in the Sixties

March 1940 By DR. WILLIAM LELAND HOLT -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

March 1940 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER