A Faculty Impression of the V-12 Program at Dartmouth

NOT THE LEAST of the war's effects on Dartmouth is the College's new appreciation of itself. Often the selfcriticism that throve in Hanover as elsewhere during the between-wars years contributed to healthy growth, but sometimes it seemed to flourish for its own sake as though there were no virtues to commend and the false prophets busily condemning liberal education could actually be believed. The corrective Dartmouth needed was such concrete evidence of what it gives to men as the issues of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE since Pearl Harbor now provide, and such a fresh view of its work as it is gaining through participation in the V-12 Program. As one member of the faculty said recently, "It took an international cataclysm to prove to us that we weren't too bad."

For the faculty the Navy V-12 Program is now entering what may prove its most valuable phase. New courses have been tested and adapted. Old have been revamped. Men teaching subjects other than their own have become accustomed to new work. Directors of co-operative courses have checked their schedules twice in practice. The new student body and its special problems have become almost as familiar as the old. And the faculty as a. whole, after two crowded terms of intensive teaching in a brand new program, has settled into a smooth-running organization which while efficiently maintaining the steady pace the new routine exacts offers opportunity for teachers to digest what they have learned.

FACULTY MORALE HIGH

So around the campus these days men are exchanging their impressions, and everywhere one finds a new confidence in mutual understanding. The faculty is friendlier and more closely knit than it has been in years, due not only to the decrease in its size as the war has carried men away but also to the V-12 Program. Unexpressed but none the less apparent are the common feeling of joint contribution in some measure to the nation's needs; the common purpose of giving the Navy the best possible results in terms of its immediate requirements, and providing the students as individuals with such humanistic insights for later life as the calendar and the curriculum permit; the common consciousness of the consideration variously shown by the administration; and the common satisfaction with the way everyone has measured up to Admiral King's injunction to "do the best you can with what you have." Then too the general shake-up the program necessitated in teaching assignments has cut through divisional and departmental lines, brought into daily association men who seldom met, set instructors of advanced courses to teaching elementary, caused men who taught comparatively small groups to lecture to large and vice versa, and given everyone a new appreciation of his colleagues and their work. Meanwhile the common body of new experience has been providing a common basis for reconsideration of the pre-war College.

Except for some formalities which by now seem routine, the general atmosphere of classes is much the same. Undergraduates are subject to similar afflictions in uniform as out, and techniques of instruction are fortunately not affected by their clothes. Today there is more need, since students have more concrete aims, to relate required work to what they hope to do in the immediate future; there is necessarily more emphasis oh the development of specific skills by various methods; and there is naturally a feeling that each student regardless of his limitations must become competent fast. In large co-operative courses, too, where daily assignments follow schedules carefully planned to meet requirements of the program, there may be more uniformity in the topic of the day and hour, but each instructor is still free to use his own approach, and there are certainly no signs of lock step. Throughout the College men are teaching as they always have and trying to maintain the usual standards without benefit of the usual calendar, curriculum, or Selective Process.

What has proved most challenging for teachers is the new student body. For some years before last summer the general kinds of men coming to the College remained pretty much the same, and after their arrival they all absorbed its spirit. Although each college generation had its own attitudes and interests, and each class its varied individuals, the teacher could expect freshmen to have the backgrounds and training exacted by the Selective Process, upperclassmen those provided by the curriculum, and all a live feeling for Dartmouth. One knew why those students came, what they hoped to find, and how they might develop with most profit to themselves and the College. From time to time, through casual talks around the campus, sometimes months or more apart, one got to know at least a few rather intimately. Then when they graduated or, later, left for the armed services, one knew what they had gained and how they would make out, and afterwards one missed their unexpected friendship. Such associations, so vital for real understanding, are seldom possible today, and consequently faculty impressions of the new students are mostly based on what can be perceived in classes and sometimes conferences.

The first thing that strikes you is that these men belong to the Navy or the Marine Corps, not Dartmouth College, which of course is as it should be. Relatively few would have come to Dartmouth had there been no war. A few others, including one from the fleet, longed to while knowing they would never have the money and now can hardly believe their dreams have come true. Some hope to return for degrees after the war. Others—no one can tell how manyare developing an appreciation that may bring their sons or even younger brothers to the College. On the other hand, most of the transfers, who were especially numerous last summer, retain their previous loyalties. Some of the rest, having always lived in cities, think of the country around Hanover as what one in desperation called "a wilderness untouched by man," and with little chance to learn to enjoy it are genuinely homesick for a familiar drugstore on a crowded corner. And many, however they may eventually look back, are in a hurry to be somewhere else. To such students Dartmouth seems a way station where what they thought an express pauses overlong, and when lacking understanding of the reasons they are impatient to get on.

Often a class of these varied men represents much more of a cross-section of American youth and schooling than one formerly. Some may have the usual kinds of backgrounds. Some may come from homes where there is very little money or schools where they have had comparatively little training. Some may be1 transfers from any of a number of institutions. Some may have been through boot camp. Some may come from all sorts of duties, including overseas, with the Fleet or the Marine Corps during periods of service up to several years. Many are likely to have had to work in shops or factories, less often offices, and sometimes on fishing boats or farms. Most feel more natural with tools, motors, radios, or machinery than books. Not a few are acutely conscious of limitations in their schooling and much more worried about their ability to meet Dartmouth standards and fulfill the requirements of their stiff program emphasizing sciences than they mean to show.

Like other entering students they have to find their way, and unlike others they have little time to do it—a number only two terms, most only four. When studying on their own, as large classes make inevitable, they are more apt to become bewildered, due to both their heavy schedules and their schooling. When taught individually, for which on the whole there is much less opportunity, they are apt to be more appreciative and to respond more effectively. Today a lot more "C's" and "D's" are being earned by honest effort instead of being given grudgingly to men able to do better if they went to work. Some students are quite as good as any in the past. Some are infinitely poorer and are being weeded out. Some instructors, especially in advanced work, have had whole classes that seemed superior. Others have definitely not. All agree, however, that many of the students are handicapped by their schooling.

The simple fact is that a lot of American boys are not taught to read and write and cipher competently. It was evident even when Dartmouth benefited by the Selective Process. Today it is obvious. No one wholly blames the schools, which have problems of their own, but perhaps as much could not be said for some influential between-wars notions of education. Anyhow the boys are the victims, and until taught better they are capable of making fantastic errors. They may not know the meanings of words they use or read, or how to find the meanings in a dictionary. They may have difficulty distinguishing what is most important in a few pages of lucid prose. They may not be able to write simple, clear, correctly punctuated sentences. They may not know how to work with fractions, let alone algebra. They may not reason independently or soundly. They may not have been trained to listen attentively or to remember what is stressed. They may never have been taught accuracy or even its importance. They often suffer from what a senior member of the faculty calls "the human incapacity to organize." They lack the tools of learning, and the college teacher is forced to sympathize with the college student who wrote he hoped "people will be better edjucated as times goes on."

Fortunately at Dartmouth they are, and as the new students learn how to work in the time they have, many improve greatly. Like Dartmouth men in the Unit, transfers from institutions whose names can be imagined adjust themselves quickly and feel the time available to do assigned work is adequate if well employed. Other transfers and men with only high school training often have to learn not only when but also how to study besides whatever fundamentals they have not been taught. So especially at first many find conditions and requirements hard.

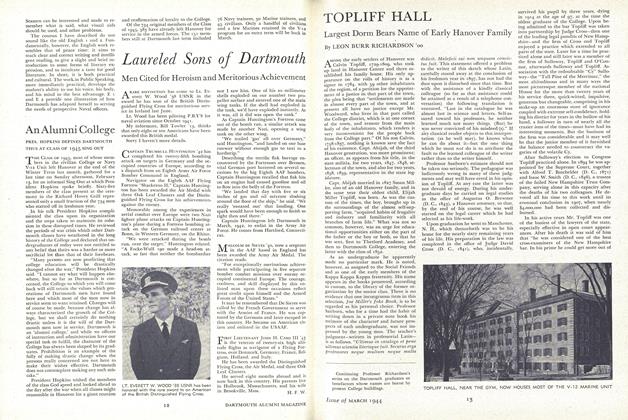

Those who meet such difficulties best are the men from the Fleet and the Marine Corps. As a group they impress everybody with their seriousness, quiet determination, and inherent qualities. They are somewhat older than usual students, they are much more mature, and they are both disciplined and individual. Not all are brilliant scholars, though some are very good, but all are a joy to teach. They come to Hanover from home and foreign waters and stations; from battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, submarines, PT boats, and mine sweepers; from Iceland, North Africa, the Caribbean, and the South Pacific. Often they come back to school, with younger students fresh from home, after several years away, sometimes as much as five. Most never expected to be able to have college training. They appreciate the opportunity and they work—like the former petty officer who spent ten hours profitably revising a four-hundred-word theme at the same time he was nightly studying physics in the washroom after lights out. or like the marine who can write "B" themes and, unsatisfied, continues to apply himself so as to learn' to write as well with less revision. Such men, no matter what grades they receive, set a standard of work all too seldom found in college students, and it is safe to say that the more men sent to Dartmouth after service in the Navy or the Marine Corps the happier the faculty will be.

LEARNING MORE THAN SKILLS

No one can tell today, any more than in the past, how much of what beyond specified instruction Dartmouth is giving to its students, but judging by known individuals, many must be gaining a good deal, whether or not they realize it yet. They are learning not only basic skills but also at least something of those ethical concepts on which our society is based. They are learning how America has developed and what the present war is fundamentally about. They are learning to think more independently and soundly, and to seek understanding, not merely knowledge. Through teachers still happily differing with texts and colleagues, they are learning there are many roads to truth and everything in print and speech is not infallible. They are learning there is much more to learn than they ever dreamed. They are more conscious of the library and benefit more from it than is generally supposed. They are impressed by personalities, they like to talk informally with their teachers, and at least one—who out of his pay is sending money home besides investing in war bonds and insurance—buys books of which he hears in class. When they can, some are electing courses in modern languages and literatures, the classics, art, history, and national cultures as well as sciences. Some are discovering the countryside, and a former welder in a war plant has written of his post-war life: "Would it not be just as well if I should forget about some white-collar job and instead get out in the country and live a real life? I now get as much pleasure out of a beautiful sunset as a raise in pay." A number who otherwise could never have gone to college have found new interests through their studies and are anxious eventually to take degrees. Nearly all are changing more than they know.

MANY APPRECIATE DARTMOUTH

One has written, "Dartmouth is everything I've ever dreamed of"; another that he regards his association with the College "a privilege and honor"; and a third: "Before I enlisted I had the idea of having a good time while the money was rolling in. .... Lately I have been thinking more and more about the future We can't have a better future if we don't fight for it, and the Navy wouldn't keep us here if it wasn't helping to win the war. I am putting all I have into this because.... it is time to settle down to a big job .... that will take all the strength and stamina I have. To do this I must be prepared, and there is no better place to get prepared than here at Dartmouth Lately I have taken an interest in the management of my country. I want to know how the men who are presiding over my country are running it, and I want to see that everything is done that can possibly be done to make this a better country."

Meanwhile teachers have been learning too. Experience of a speed-up even speedier than some educators sought before the war has shown everyone that such instruction though necessary now is certainly not desirable for the liberal college. Students need time to secure a broad foundation, find and cultivate special interests, enjoy the country, make friends, read, talk, play, assimilate, reflect, absorb the real spirit of the College, and grow up. Teachers need regular periods in which to read, revise their work, and get outdoors themselves. Some would like less emphasis on extracurricular activities, in which undergraduates have too often found substitutes for working at either studies or real jobs. Some would be happy if "recreational activities" were abandoned in favor of exacting physical training with stiff tests that all except the incapacitated had to pass. Some do not want big-time football—for many reasons, among which is concern for one of their most respected colleagues who when told Dartmouth was to play Notre Dame fell over backwards in his chair. Those once skeptical of the Selective Process have changed their minds, and no one who has taught transfers doubts that Dartmouth's academic standards are as high as any, but many wish some way might be found to bring to the College more men of character and ability who can not afford the liberal education they deserve. No curriculum eventually developed for the post-war college can do more* than such men to help Dartmouth meet its obligations to the postwar world.

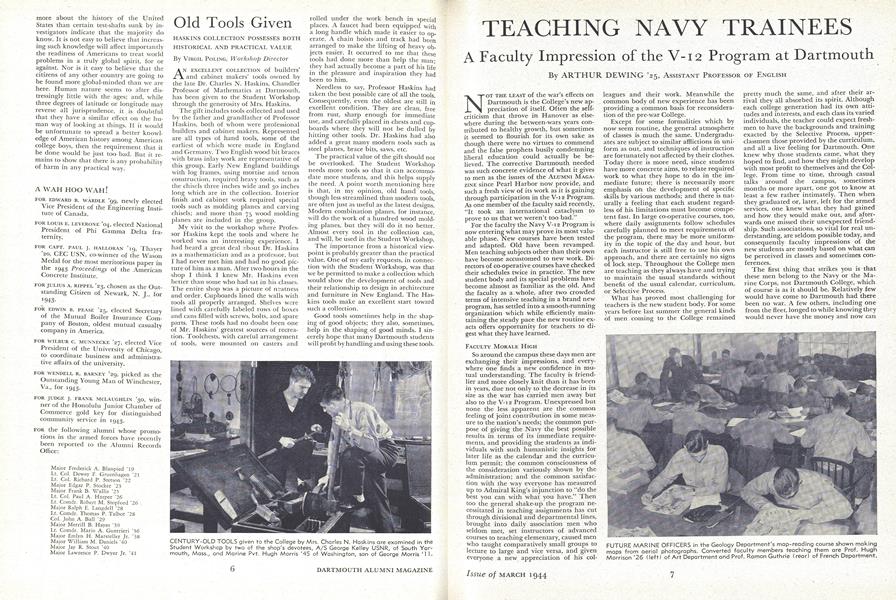

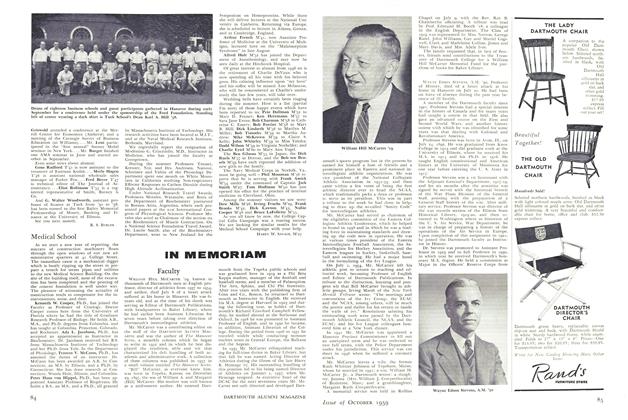

FUTURE MARINE OFFICERS in the Geology Department's mop-reading course shown making maps from aerial photographs. Converted faculty members teaching them are Prof. Hugh Morrison'26 (left) of Art Department and Prof. Ramon Guthrie (rear) of French Department.

THE AUTHOR OF THIS FACULTY ARTICLE, Prof. Arthur Dewing '25 of the English Department, shown holding a student conference in Sanborn House with A/S Philip S. Hodge of Salem, Mass., a former 3rd Class Yeoman just completing his first term in the V-12 program.

NAVAL WORLD GEOGRAPHY, shown being taught in the summer term by Prof. Trevor Lloyd, is one of the new elective courses with which the College supplements V- 12 training.

V-12 MEN FROM THE FLEET have proved to be among the hardest working students in the Navy program at Dartmouth. Shawn in this dormitory study scene, with their crows transferred from their sleeves to the wall above their desks, are Rippey T. Shearer (left), former Machinist's Mate, and Milton S. Kessler, who held the rating of Storekeeper.

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsWith Big Green Teams

March 1944 By Dick Gilman '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

March 1944 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931

March 1944 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, WILLIAM A. GEIGER -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the Editor'Round the Girdled Earth

March 1944 -

Article

ArticleARTHUR FAIRBANKS '86

March 1944 By DR. FREDERIC P. LORD '98 -

Article

ArticleTOPLIFF HALL

March 1944 By LEON BURR RICHARDSON '00