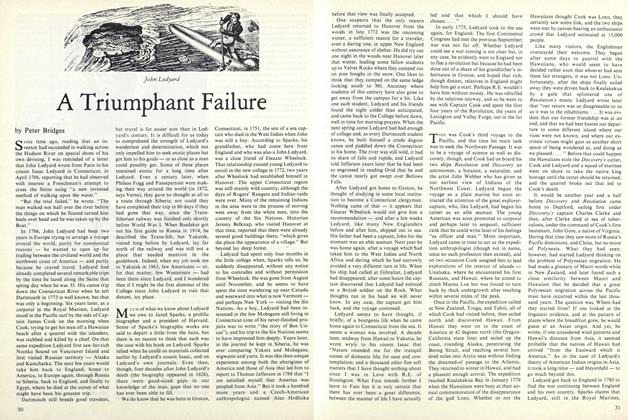

What does a professor of government have in mind when he shows his class slides of battling baboons? Professor Roger D. Masters sees nothing strange about it.

The Government 72 (Biology, Medicine, and Politics) lecture given by Masters last month was entitled "Candidates and Chimps," and he did indeed show slides of discordant primates in their natural habitats accompanied by slides of another species in its natural habitat the politician on the campaign trail. Drawing from the work of ethologists Michael Chance and Konrad Lorenz and others, Masters has formulated his own theories on the behavior of political candidates and shaped analogies about animal and human behavior. Many of his illustrations are drawn from the 1972 presidential confrontation of Richard Nixon and George McGovern. The purpose? To show that a political contest is not so much a matter of electing the best man for the job as it is an attention-getting proposition, i.e., whoever draws the most attention will win the election. Masters argues that, if this is the state of our electoral process, there's something not quite right about it.

In effect, what the Chance and Lorenz studies show is that animal behavior is very much a matter of body language. A chimpanzee with teeth bared and arms stretched over his head is attempting to scare away an enemy with a threatening posture. A 1972 Newsweek cover photograph shows a smiling Richard Nixon with his eyes looking upward. His teeth are showing, too, and Masters points out that we can read his look as one of confidence. The photograph was taken soon after Nixon's defeat of McGovern. By the time Nixon could not deny his involvement with the Watergate break-in, his teeth were no longer showing in press photographs and his eyes were downcast a gesture of defeat.

Masters' point is that animal behavior is a phenomenon quite distinct from the instinct or the drive of the animal. For example, as a result of mothering, a female gains dominance over a dependent infant. The instinct involved is that of a child requiring attention in order to survive, but the female or agent of that attention does not have to be the real mother, and the dominance the female gains is merely a by-product of her action of caring for the infant.

Similarly, the United States needs to elect a president every four years. But the candidate who is ultimately elected to the Oval Office may not have been the most qualified. His dominance over the country is a by-product of the voters having chosen him. In the case of the mother and child, the most important thing is that the child receives the mothering it requires. The needs of a nation are somewhat more complex, however, and Masters suggests that the voter is not critical enough in his appraisal of the dominant figures in American politics.

With election '80 right around the corner, the question is whose teeth are showing and whose aren't. Masters, an avid Anderson supporter, claims his candidate's lower row of pearly whites has been making an appearance a sign that Anderson is not down yet. On the other hand, what has happened to the Jimmy Carter grin? Masters says its a sure sign of something. Perhaps we should consult an ape.

There may be, Roger Masters thinks, more kinship here than usually acknowledged.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Triumphant Failure

October 1980 By Peter Bridges -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWhat It Was Was Grid-Graph

October 1980 By John R. Scotford Jr. -

Feature

FeatureA Collection of 'Erotic Capital'

October 1980 By Margaret E. Spicer -

Article

ArticleIntellectual Athlete

October 1980 By Don Rosenthal '81 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1978

October 1980 By JEFF IMMELT

Article

-

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE FORCED TO ANNOUNCE CLOSING OF APPLICATION LIST

March 1921 -

Article

ArticlePROF. E. P. KELLEY SENDS UNIQUE CUP TO COLLEGE

August, 1926 -

Article

ArticlePhi Sig Goes Local

May 1956 -

Article

ArticleDevelopment

June 1976 -

Article

ArticleTuck School

April 1951 By K. A. Hill, H. L. Duncombe -

Article

ArticleTHE HITCHCOCK CLINIC

January 1933 By Natt W. Emerson '00