Social Sciences Aim To Produce Graduates Distinguished

IN JANUARY, 1937, an article by Professor Robert E. Riegel appeared in the DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE which gave a detailed account of the background of, and the justification for, the new curriculum in the social sciences at Dartmouth as adopted by the faculty in the autumn of 1935. The February, 1939, issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE contained a further description by Professor James P. Richardson of the way in which the new curriculum was functioning in practice. The justification for another article at this time lies in the obvious interest among the alumni, as manifested in the numerous letters in response to the attack upon Social Science 1-2 made by Mr. Francis M. Qua '11, in the issue for January, 1940.

The author of the present article was requested by the Administration to serve as chairman of the new course, Social Science 1-2, in February, 1936, and has since acted in that capacity. He willingly accepts therefore the responsibility for the details of the course, although in practice most of the decisions upon policy and details have been reached by majority vote in structors chosen from the departments of economics, political science, sociology, history, and biography. It should also be pointed out that the chairman and his staff have been working from the beginning under a mandate which determined the general scope of the course and which declared that the staff was to be a cooperative one. This mandate, which the chairman and the staff could not change at will, is embodied in a report by a faculty committee which was accepted first by the Social Science Division and then by the faculty as a whole. It goes without saying that the general plan of the course was acceptable to the chairman, otherwise he would not have been willing to undertake such a responsibility. Mr. Hayward's statement in the March issue, however, that the author of this article was the "founder" of the course, is certainly too strong. The chairman was not even a member of the committee which drew up the report upon which the whole course has been constructed.

Before giving a history of the course and an account of how it has been conducted, it seems desirable to point out briefly certain points upon which Mr. Qua was definitely misinformed. (1) His informant implied that no attention had been paid in the course to the Bill of Rights or the Glorious Revolution of 1688. These points have always been covered in the course. (2) His informant implied that the Encyclopoedists of the 18th century were discussed after the study of the American Revolution. As Mr. Douglas W. Alden pointed out in his letter in the February issue, such an arrangement would be "weird." Naturally a study of 18th century thought must precede the American and French Revolutions to make those changes more intelligible, and this order has always been followed. (3) The course has never made any study of comparative religions in the sense in which that phrase is generally used. An attempt has been made to show briefly the part which the church has played in the general thought of the periods covered, its importance as a social institution, and the changing relations between church and state. (4) Mr. Qua was given the impression that a very considerate portion of the course was devoted to the book by Dean Christian Gauss of Princeton entitled APrimer for Tomorrow. This book was used as an introduction to the course during the first three years, but is no longer used. The time devoted to it was never more than six assignments out of a total of eighty. The book was an attempt by a highly intelligent educator, who is not a social scientist himself, to examine into the causes of the various perplexing social problems of the contemporary world and to make some very tentative suggestions for improvement. It was well written and challenging, and did make an impression upon the students. It was useful, most of the staff thought, in pointing out and emphasizing those fundamental problems of our time, towards understanding the background of which most of the course was to be devoted.

HISTORY PREREQUISITE TO UNDERSTANDING A basic premise of Social Science 1-2 is that the history of anything helps to make it more intelligible. A history of the background of Social Science 1-2 may therefore help to explain why such a course was adopted at Dartmouth. The first orientation course at Dartmouth, in the general sense in which that term is employed, was worked out during the World War in compliance with government requirements, and was known as the "War Issues" course. After the war that course was abandoned and its place was taken by a one-semester course entitled "Problems in Citizenship," popularly known as "Cit." This course went through many transformations, but in general it was devoted to a discussion of contemporary political, economic, and social problems. Some historical background was given, but there was not time for very much. When "Citizenship" was inaugurated a very large number of students, probably half of them, were still taking the old History 1, as worked out and developed by the late Professor Herbert Darling Foster, to which Mr. Qua paid a striking tribute. History 1, as it was being given when the present author taught in it during the twenties, consisted of a study of Modern European History since 1500, and was very largely political in scope. When a new curriculum was adopted in 1925 it became possible for the student to satisfy his social science requirements, beyond Citizenship, by taking two one-year courses in six departments listed as social sciences. The result was a steady drop in the enrollment of History 1 until only a relatively small proportion of the students were receiving any background in European history.

To the Department of History, and to many other members of the faculty, this seemed unfortunate. To the social scientists as a group it seemed desirable that the basic course in social science should be historical in' character. At the same time the economist and sociologist were interested in seeing the scope of such a course broadened far beyond the political history covered in History 1. It is very doubtful whether the Social Science Division or the faculty as a whole would have approved in 1936, as a required course for all freshmen, anything like the old History 1.

One of Mr. Qua's fundamental criticisms of Social Science 1-2 is that it is too contemporary, that it does not reach far enough into the past. The author of the present article is by training a historian and admits freely that ideally he would like to go much further back. As the course is organized many significant aspects of the past have to be omitted. At the time when the course was adopted there was much discussion among the faculty committees and among the faculty as a whole on this point. Several professors criticised the course on precisely the same grounds as Mr. Qua has done. Several proposals were brought forward to have the course go back to ancient times. The general opinion, however, was that such a course would be very thin, and that its content could hardly be more than that given in the secondary school courses on the history of civilization which are becoming more and more common.

It is certainly true, however, that a reasonably good survey of European political history from the fall of the Roman Empire to the present might have been given. Indeed such courses are being given in many institutions. Such a course could certainly not have been made a required course, however, for about half of our students have already taken similar courses in secondary schools and it would be very undesirable to submit them to a repetition of this work.

Social Science 1-2 was then designed primarily as an introductory course to the social sciences. An examination of such introductory, or orientation, courses throughout the country would show that they are divided into two classes: (1) those that are primarily historical in character; (2) those which are analytical and deal with current problems. In 1936 at any rate the majority of the social scientists at Dartmouth were convinced that some common historical background was desirable which might be taken for granted in more ad- vanced courses and upon which the latter might build.

There were several objectives in the minds of those who had the duty of planning the course in detail. In the first place, the course must arouse student interest in social, economic, and political problems. The old course in Citizenship had been remarkably successful in that direction. There was great danger that a required course, primarily historical in approach, might seem so repetitious to many students as to result in a decreased interest in social problems. Certainly the staff in Social Science 1-2 would strenuously deny that it was deserting the traditional aim of the American liberal arts college to train for intelligent leadership in citizenship. On the contrary it believes that the course as organized does give a body of solid background factual material of great importance for an understanding of our modern world. That we have succeeded to a considerable degree in avoiding repetition was proved last autumn when we gave to the entire entering class an objective examination based upon the material used in the course during the previous year. Only eleven members of the class showed a sufficient knowledge of the material of the course to allow us to exempt them from taking it. Repeated student questionnaires, unsigned, have indicated, moreover, that the amount of repetition in the course is not serious.

In the second place, the course was to serve as a background for later work in the social sciences. It must therefore choose material which would be significant for the sociologist, economist, and political scientist as well as for the historian. As a result straight political history was minimized, and economic and social history emphasized. To give an example, the economist and sociologist are more interested in a careful study of the rise of capitalism and the development of labor movements than in a detailed treatment of the various phases of the French Revolution or in the traditional emphasis upon the successive campaigns in the Napoleonic Wars.

In the third place, there was the problem of the amount of American material to be included. The staff held very strongly that the United States should to some extent be studied as a part of western civilization, and that there would be very decided advantages in making comparisons and contrasts between certain American and European developments. At the same time we recognized that nearly every freshman had taken in secondary school a course in American history. A student questionnaire, for instance, in February, 1939, showed that over ninety per cent of the freshman had done so. We have sought therefore to recognize this fact. No complete survey of American history has been attempted. The political framework is taken for granted, and the chief emphasis is laid upon significant economic developments. An effort has been made to introduce American material which would show how developments in the United States compared with those in Europe. This year we have used a book which covered concurrently English and American economic developments for much of the early 19th century.

In the fourth place, we have believed that there are very definite values to be gained from the historical approach to a study of the social sciences. We are convinced that any contemporary problem is understood more intelligently if its background is known. To be historically minded is to have become accustomed to ask how a thing "got that way." We are constantly interested therefore in development and evolution. Incidentally we believe that there are certain disciplinary values to be gained in being able to keep a course of developments straight, and in proper order. We do not emphasize dates as such, but we penalize severely the student who gets his facts muddled. We emphasize constantly cause and effect. We ask the students again and again to describe the various factors which entered into a specific situation and to evaluate the relative importance of each. We hope that such a training does tend towards impartiality and a judicial frame of mind. We attempt to avoid dogmatism and the final answer to anything. After all, this is a freshman course.

There were certain members of our staff who advocated that each field of interest in the course should be treated separately and topically. For instance they urged that we should devote one part of the course to the development of government, another to international relations, and a third to economic organization. Such an arrangement has many advantages, but the majority felt that it sacrificed the unity of history at any one period. As a result we reached a compromise. The course is divided roughly into four large periods: (1) the background up to about the middle of the 18th century; (2) the period from 1750 to 1870; (3) that from 1870 to 1914; (4) that from 1914 to the present. Within each period a more or less topical arrangement has been followed.

A more adequate idea of what Social Science 1-2 does cover will be gained from the following abbreviated outline of the course: 1. Medieval and early modern backgrounds (9 exercises): feudal society; growth of commerce and capitalism, the Commercial Revolution; medieval intellectual outlook, scientific revolution, age of reason; absolute versus limited monarchy.

2. The American Revolution (3 exercises): causes; character; the background of the Constitution and its framework.

3. The French Revolution (4 exercises): background; the pattern of revolution; permanent reforms; Napoleonic Empire; age of Metternich.

4. The Industrial Revolution (8 exercises): general character; industrial, agricultural, transport, and financial developments in England and the United States in the early 19th century; spread to continental Europe; economic and social effects; laissezfaire and the reaction.

5. The Nineteenth Century—Liberalism, Nationalism, Science (10 exercises): the revolutions of 1848; the wars for national unification; conflict of social ideals in early 19th century; liberalism and nationalism in the United States; internal developments in Great Britain, Germany, and France, 1870-1914; 19th century science and its implications.

6. Changing Social Ideals in the Late 19th Century (6 exercises): capitalism and laissez-faire; working class ideals and programs—Marxian Socialism, trade unions, cooperatives; social legislation.

7. The United States after the Civil War (5 exercises): transportation; industry; labor; agriculture; immigration.

8. Imperialism (6 exercises): general aspects; the Far East; Latin America.

9. The World War (6 exercises): diplomatic background and causes; military and economic aspects; entry of the United States; peace settlements.

10. The Post-War World (16 exercises): the new science and technology; importance of propaganda; Soviet Russia; Fascist Italy and Germany; internal developments in Great Britain, France and the United States; international relations and background for the present war.

There remain two fundamental and somewhat related criticisms which were made by Mr. Qua: (1) that the course is too advanced for freshmen: and (2) that it is radical in tendency. The staff would admit frankly that occasional individual assignments have been beyond the freshman level,, but we do not believe that the course in general is too difficult for the average freshman. The assignments average, from twenty to thirty pages in length. Aid is given to the students by the syllabus, which not only helps to organize the individual assignments, but also serves to tie the course together. Of course we want college work to be different from secondary work and we try not to spoon feed the students too much. We have tried to select readings which are more mature than those to which they have been accustomed. Moreover many instructors make no pretense of covering \each day's assignment point by point, believing that if an adequate opportunity is given for questions, it is more valuable to discuss the implications of the reading. Naturally certain points in nearly every assignment have to be emphasized or explained.

It is much more difficult to make an answer in regard to the charge of radicalism. So much depends on what is meant by that term. Certainly our staff contains no Communists or Fascists. The great majority of the staff would probably be classed as moderate liberals, with some conservatives and some advanced liberals. This semester twelve of the seventeen members of the staff are over forty years old, so it is not an aggregation of hair-brained youngsters by any means. As liberals the staff has chosen, I presume, a body of readings with a liberal slant. The great majority of the readings, however, are purely historical in character and have been chosen because they cover the ground in the most satisfactory way for our purposes, are the most readable presentations, and embody the results of the most recent scholarship. In the few cases where the readings are of a controversial character, the student is usually warned in the syllabus of the bias of the author.

As liberals the staff also believes that college students should be introduced to new points of view. The aim of the liberal arts college, in so far as the social sciences are concerned, is to produce broad minded citizens, cognizant of recent trends, able to keep a cool head in the midst of controversy. The college graduate should be neither a crack-brained visionary nor a blind reactionary but a man of judicial temperament, intelligent, and tolerant. Cynicism as the ultimate product is undoubtedly bad, but a certain amount of cynicism is necessary for the individual to make a re-evaluation of his ideals so that those ideals shall be really his own, not merely those of his family or of his social background. We do not think, moreover, that college freshmen are too young or immature to begin such a re-evaluation. Humbly, we hope, and without dogmatism, the staff of Social Science 1-2 is trying to make a contribution to that end.

PROFESSOR JOHN G. GAZLEY

Intelligence, Tolerance

CHAIRMAN OF SOCIAL SCIENCE 1-2

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleGordon Ferrie Hull

June 1940 By STEARNS MORSE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1915*

June 1940 By CHARLES R. TAPLIN, RUSSELL B. LIVERMORE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

June 1940 By CHARLES S. McALLISTER, CRAIG THORN JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

June 1940 By ALBERT I. DICKERSON, G. WARREN FRENCH -

Article

ArticleWhen Spring Comes

June 1940 By BOYNTON MERRILL '15, D.D.

JOHN G. GAZLEY

-

Books

BooksTHE DRAMA OF UPPER SILESIA

June 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksFRENCH FOREIGN POLICY DURING THE ADMINISTRATION OF CARDINAL FLEURY, 1726-1743. A STUDY IN DIPLOMACY AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT.

November 1936 By John G. Gazley -

Books

BooksTHE UNITED NATIONS IN ACTION

March 1951 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksVICTORIAN ORIGINS OF THE BRITISH WELFARE STATE

May 1961 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksTHE MRP AND FRENCH FOREIGN POLICY.

APRIL 1964 By JOHN G. GAZLEY -

Books

BooksENJOYING IRELAND.

FEBRUARY 1967 By JOHN G. GAZLEY

Article

-

Article

ArticleCAMPUS NOTES

January 1922 -

Article

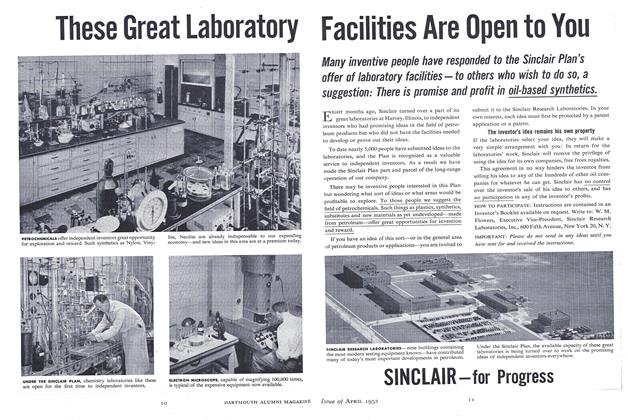

ArticleThese Great Laboratory

April 1952 -

Article

ArticleA Treasured White Elephant

December 1992 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1932 By J. S. M. '33 -

Article

ArticleHow Good Is the Product?

May 1944 By P. S. M. -

Article

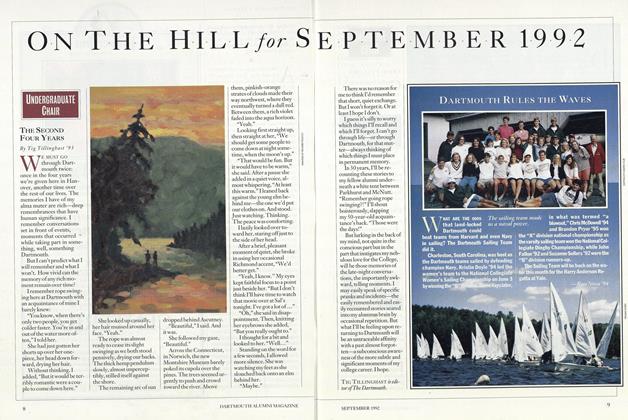

ArticleThe Second Four Years

September 1992 By Tig Tillinghast '93