Teaching in Campus Classrooms and Wilderness Cabins Has Immortalized Doc Griggs to Dartmouth Men

ALL OVER THE UNITED STATES, Dartmouth men reading this article will turn the page and say to themselves, "Doc Griggs is a swell fellow. I wish that I got half the kick out of my work that he does out of his. I wish that I was doing half as good a job as he is." Man can ask little more from life than this.

Superbly mounted birds stood in their niches around the small oak study. A fire talked to itself on the hearth. Doctor Leland Griggs' head and shoulders came through the door and his deep monotone asked, "How do you gentlemen like your steaks?"

There were thick steaks at the plain refectory-type table, and French fried potatoes and delicious peas and golden crusted bread with huge pats of butter and for dessert a mixture of half-frozen Whipped cream and walnuts. Then there was black coffee and a choice of tobaccos md easy chairs in front of the fire. Doc Griggs snapped on a single bridge amp, carefully shaded the rays so that they were concentrated onto an old ladder sack chair.

"We'll start the examination now," he said. "Put your first picture on that chair seat. Tell us where you took it, why you took it, how you took it, how you worked uP the negative and what paper and deeloper you used in your enlargement. Explain what principles of pictorial composition it illustrates and how the picture night be made better."

Two hours later the last man had shown his final print. The fire had burned down, he bridge lamp was out. Here and there our cigarettes glowed in the half darkness. We waited quietly. Dr. Griggs cleared his throat and using his cigar as a pointer "Davis, you get an A for the course. You've got good technical knowledge. You've worked hard and you've improved yourself greatly—" and so around the room. Each man received his mark and a quick, concise, non-debatable estimate of himself and his work.

As we put on our sheepskins and went out into the cold Hanover night we felt a very tangible bond with our teacher. But bond perhaps is an incorrect term. It was rather a quiet flowing current of emotion. From us to him, the respect of really earnest pupils to a wise and sympathetic teacher. From him, to us, the teacher's satisfaction that his efforts were really appreciated and that they had borne some fruit.

EARLY COLLECTOR Leland Griggs was born in 1878, on August 22, on a farm near Rutland, Vermont, the son of Joseph Grafton and Julia Closson Griggs. Before his family moved to Lancaster, Mass., when he was nine years old, he attended a small private school. Now this class had for teacher a recent graduate of a then most progressive Normal School. The young woman, who taught better than she knew, required the young Leland Griggs to collect frogs' and birds' eggs and minnows. This simple collection aroused in his mind a curiosity regarding the intricate processes of nature that has never been satisfied.

At Lancaster he went through grammar school and continued his long trips afield. In high school he earned considerable money trapping; he played football and won a prize of five dollars at the Worcester East fair, held at Clinton, for the best butterfly collection exhibited.

He entered Dartmouth in the fall of 1898. Since he entered with Greek and Latin he had to continue classical subjects into his sophomore year. Once those requirements were out of the way he crammed into his curriculum every course in Biology and Geology that was permitted.

UNUSUAL PREPARATION

He graduated with the class of 1902 and spent the next three years at Hanover acting as laboratory assistant and studying under Professor William Patten for his Doctorate in Biology.

Doane College, a co-educational institution with one hundred and twenty-five students at Cretet, Nebraska, located near Lincoln, needed a full time professor in Biology. The now Doctor Griggs secured the position, but when he arrived at Doane, he was told that he would teach not only Biology, but also Dramatic Expression, Geology and act as assistant football coach—all this for eight hundred dollars per year.

His predecessor in the chair of Biology had just been discharged for teaching the then frightening doctrine of Evolution. But Dr. Griggs taught it openly, enthusiastically and was not checked or criticized. The Trustees realized that he was a man, like them, sprung from the soil. He did not put on the airs that a less wise scholar from an Eastern college might easily have assumed. "I didn't high hat them," he says.

In addition to his formal work at the college, he was urged to tour the countryside lecturing upon the evils of nicotine. This he refused to do, but compromised by giving up the use of tobacco during his three years' stay. The second year at Doane the course in Dramatic Expression was dropped and he taught debating. Rough and ready were the debates on Evolution held at the Y. M. C. A. Halls through that region. Now in theory, the formal training of Leland Griggs was all wrong. When he received his B. A. from Dartmouth he should have gone directly to Harvard or Yale or Columbia for his Doctorate. But he stayed at Hanover and as part time student, part time laboratory assistant, he secured inspiration and training that he could have found perhaps nowhere else. He learned the hard way, just how many things can go wrong in a demonstration or in preparing a specimen. Professor Patten taught him slowly and thoroughly.

Then he went to Doane. His quiet tact and understanding overcame the instinctive hostility of the Westerners to a young professor from the East. The rough and ready debating taught him to think quickly on his feet and place each word with telling effect. The sudden assignments to teaching Dramatic Expression and football coaching tested his mettle. Theoretically his preparation to teach at a proud old Eastern college was most inadequate. Actually, it was magnificent.

Then he came back to Dartmouth in 1907 and taught until 1913, when he voyaged to Cambridge and observed English teaching methods, the philosophy and psychology of English teaching and the background from which the students came.

He sailed from England just before the First World War and returned to the beloved Hanover Plain. Since that day, except for observation trips, he has not left it.

Now the man was ready to enter upon his life work. He had bought the tools of his trade by years of sweat and study. He had sharpened them again and again, each time bringing them to keener cutting edge. He was ready to go to work.

That was a quarter of a century ago. A quarter of a century gives a man adequate opportunity to show what he can do in his chosen profession. Let us examine the results.

It is agreed that Dr. Griggs is not a productive scholar. He is a teacher and an observer. Debating as to which man is more valuable to humanity, the teacher or the productive; scholar, is much like debating as to which came first, the hen or the egg. Obviously the teacher cannot teach until the productive scholar has given him the books, the data, and the charts. But the books and the tables and the charts that the productive scholar has created remain sterile and dust covered unless there comes a teacher to give them meaning and significance.

Leland Griggs is a great teacher.

As an observer he made three trips to New Brunswick and three trips to New- foundland. He remarks, "My friends called them moose hunting parties, I averaged three shots every thirty days, so I guess there wasn't too much hunting." There he observed mammalian life. The drift and movement of game, their feeding habits, their mating and life cycle were closely studied. Hundreds of pictures were taken and many guides interviewed. When meat was needed, a beautiful .30-06 set trigger Mauser came out of its case, "That rifle has fired at moose and caribou and deer and when I got to them they were all dead. I take only standing shots, I won't take a running shot for the animal may get away and die a slow death. Yes, it's a good rifle."

About this time he turned a very definite corner in his teaching technique. He began to ask the leading men in his classes what was wrong with his methods of instruction. No one had said that anything was wrong with them. He was getting good results. But he was not satisfied. In reply to these questions, one student advised him not to use so many notes when lecturing. "If you're a full professor and still have to read all your lectures and use notes and tables, just how do you expect us students to keep all that stuff in our heads? If you can't, we can't." Since that day he has never carried a set of notes to class. At the beginning of each semester he draws up an outline of each course and what he intends to accomplish. He prepares each lecture. A few simple notes go with him to class. But they are merely topical headings.

He taught Botany, Zoology, Embryology and Entomology. He helped Professor Patten in the old freshman Evolution course by doing much of the conference work. From 1926 through to 1933 he headed the department of Biology. To- day he handles his popular Zoology 17 and gives a special Zoology course that is a review for comprehensive examinations.

He is also associated with a group of men teaching Zoology 1-2, the elementary course for which he has been famous through the years.

There, in a short paragraph is a quarter of a century of professional life. Only when you interview brother faculty members and alumni do you realize just how much has been packed into that quarter of a century.

For fifteen years he did not miss a single recitation, laboratory period, or examination. That in itself is a remarkable record. But when you begin to realize all the extra-curricula activity in which he engaged, then you are amazed at this devotion to duty.

First of all, the Outing Club, the Canoe Club, and Bait and Bullet could not exist in present form if it had not been for Leland Griggs' active help. He inspired Johnny Johnson to make the gifts that founded the Canoe Club. There was scarcely a year when these organizations did not owe him in aggregate four to six hundred dollars. He always got his money back, but usually without interest. And in those days savings banks were paying four per cent. There was scarcely a day when some Outing Clubber or white water man or hunter did not come to him for advice on the conduct of their organizations. It does not cost anything to give advice. But those informal conferences consumed hours and hours of precious time that were definitely alloted to other work. The hours given were made up by working when other men were taking their ease.

Then Leland Griggs began to hold his cabin parties. New Moose was the gather ing place. Fall and winter he cooked young pig on Monday, Wednesday, amd Saturday nights. In the spring there were strawberry shortcake feeds. One memon. able springtime, strawberry shortcake wa made and served forty-nine out of fife nights, and 1300 boxes of berries wer used.

Every organization from the football team to the glee club held banquets a New Moose. Dr. Griggs was cook and host and general manager. Many of his friend felt that his generosity and skill was be ing deliberately used by groups too selfish or too lazy to organize their own parties But he felt that the time and drudgen expended was well worth while, if for few hours he could get the men off the hard pavements and out from under the electric lights and to a candle-lit cabird where they could sit in front of an open fire. "You never accomplish anything be fore or during supper or right afterwards. But when the fire begins to die down you can get under their skins." At these cabin parties countless men for the first time saw how stars look through the tall spruces, and listened to the song of brook in the dark, and heard the nigh wind sing through the trees. And many of those men have never forgotten, and gome back again and again and again.

So broad are his sympathies that his could not be clannish and run with his own kind. Doubtless among the under graduates of the period he would in finitely rather have sat at table with such students as Jack Titcomb who once killed a crow on wing with a snap shot from hi pistol; or Ruff Miller, who could swimming his canoe through the brawling white water; or Bob McKennan, who knew the lone cold trails; or Line Davis, who could lecture informally on the relative intensiting of light for picture taking at each season of the year and at every time of day Cabin parties with such men would have been so easy, for they all belonged. Be instead he deliberately took the other way and with infinite patience showed the un initiated a few of the many wonders nature.

Not a few people have thought they were paying tribute to Doc Griggs where they pidgeonholed him with the nea phrase "He is a modern Thoreau."

Now Thoreau was a keen observer man and nature. He was a most able writer. He was a philosopher. He wa something of a recluse and moved in small circle of friends.

You cannot conceive of Thoreau, provided you could bring him forward one hundred years, giving up his sleep and jus leisure to show men the nature he loved. You cannot conceive of him listening patiently hour after hour to the thoughts of undergraduate students. And you cannot conceive of Leland Griggs confining his personality to a small group of intimates. The comparison is rather poor.

The work observing animals in Canada required much picture taking. He acquired very definite skill with his Graflex. He discovered the infinite personal satisfaction that results from taking a good negative, and then making an enlargement that conforms to the rules of sound pictorial composition. He could not deny this satisfaction to others. From 1921 to 1925 he taught a course in photography. This course was limited to six men, for his Hudson was a seven passenger car and there was just room for him, six students and their cameras.

In order to be able to study animals intimately and to have them ready on hand to serve as models for his camera, he built back of his house a large cage, strong enough to hold a grizzly. There was Jack Johnson the bear, and Zimran the timber wolf, and coyotes and woodchucks and coons and porcupines and hawks and owls. The camera studies that he produced have seldom been equalled for their fidelity of detail and splendid technique of execution.

Some people objected to this series of pets. But no one in his right mind argued with a big quiet man who was leading a big quiet timber wolf on leash.

Late one September he was asked to talk at a freshman smoker. He intended to open his remarks with a few witticisms and then swing into the serious part of the address. The serious part was never delivered. T he men were so convulsed by the opening sallies that they refused to take any part of the speech seriously. So he gave up trying Ito be serious at freshman smokers and for I thirteen years gave the same talk with infnite variations and uniformly explosive results.

The Griggs humor rests on as cunning change of pace as ever used by the best big league pitcher. There is overstatement, understatement and an absolute monotone. The climax is delivered with superb timing, a dead face, and a cavernous sigh is if that particular word was to be his last. He gives his audiences the truth, the Whole truth and as much more than the ruth as they will stand. Best of all, the Giggs humor runs sweet and clean. It does not depend upon a current wise crack or upon scorn or ridicule. It is fundamental humor and hits as hard today as it did years ago.

These talks to the Freshmen led into a Series of trips with Dean Laycock to alumni featherings. "I played the fool and gave them the fun, and Laycock gave them the sentiment. He made a good team. Craven said I was such a good speaker because he nearly had to flunk me in Public Speaking."

There was a small matter of working up a lecture on spider webs. To illustrate this lecture, 100 lantern slides were made from photographs of spider webs. Very simple say you at first consideration. But when you stop to consider that spider webs can be photographed best when the morning dew is on them, and that the dew vanishes with the morning sun, and that you cannot make good pictures without that sun, then you begin to understand the problem and the very real work entailed.

While Dr. Griggs was engaged in all of these activities he was teaching, teaching, teaching. Constantly he was re-building his courses and his technique. The end result is that hundreds of Dartmouth men remember him vividly and what he taught. While they were under him they were not conscious of working especially hard. They knew he did not begin to give the technical detail offered in other classes, but what he gave them stayed.

It is something of a question whether Dr. Griggs teaches Botany and Zoology or a course in the appreciation of nature. Long ago he decided that he was not going to strive primarily to create great Zoologists or Botanists, but rather he was going to open the eyes and minds of the men under him to the whole picture of nature. He would show them the steady flow of life and the great dependence of one specie upon another. He would show them the earth and the air and the water and a great Spirit breathing the breath of life into all things that walk or swim or fly.

So popular did his favorite course, Zoology 17 become, that he had to change it from an eleven o'clock to an eight o'clock in order to weed out all but the really serious.

It is hard to explain just what is accomplished in this course. The men are told that if they merely attend the lectures and do a few book reviews they will get a passing D, provided they turn in a good examination. And they will even be told what the examination will be. But if they really want to take off their shirts and work, then higher marks are possible.

Several good books on philosophy must be read and reviewed, such as Hudson's "Green Mansions" and "Far Away and Long Ago." In groups limited to two or three, the men spend an evening at Doc's isolated cabin at Clark Pond. It is a small cabin twelve by sixteen feet. There is a stone fireplace. After supper is over and the dishes are done the men sit around the fire and give their book reviews orally.

There is the fire on the hearth and a full stomach and a clean drawing pipe. There is no telephone, or radio, or traffic to interrupt. There is simply the teacher and the students and the fire.

It is hard to conceive a more favorable setting for the transmission of ideas from the teacher to the student. Life for the moment is reduced to simple proportions. Time does not exist. Then it is midnight and the return to Hanover and the students know that they have undergone a pro- found experience.

Each man must undertake one or more field projects. The return of the birds in the spring and their food and habits; the community life of a beaver colony; the detailed organization of an ant hill are good examples of such studies. The proper working up of such a project requires hours of reading and hours and hours afield.

There are four or five guest speakers for the class every semester. There is always one from the Museum of Natural History in New York. Dr. Griggs urges his men to take at least one course in philosophy in order to gain a basic understanding of the world in which we live and of the great minds that have explored the fundamental concepts of life.

Dr. Griggs feels that his college year has been successful if four or five men express a real desire to take up the teaching of Biology as a life work, if ten per cent of the class have become permanently interested in the outdoors and if a good portion of the remainder have secured an appreciation of nature that they will retain through life.

He has been able to secure such results only by constant experimentation, by an elimination of non-essentials, by a systematic study of how best to arouse the student's curiosity and to keep it aroused.

Obviously it has been hard for him to eliminate much material from his courses. His store of knowledge is so vast that one of his contemporaries remarked, "Griggs has so much packed in his head that when he gives you an answer to a question you are amazed not at what he says, but at what he does not say."

The man is habitually silent. This is not because of a slothful unappreciative mind, but because he feels that when one is silent the mind can be working. You may travel with him through a new and beautiful countryside and he will not speak half a dozen times. But you know that his eyes and his mind are never at rest and that he is drinking deep of each passing scene. After supper you may remark on some vista seventy miles back along the road. He will recall it in detail and better your description.

Just as he has deeply affected the lives of other men, so have other men affected his life. In his early years Dr. Patten influenced his professional life. In later years, John Dallas, now the Episcopal Bishop of New Hampshire, affected his spiritual life. For fifteen years Doctor Griggs was Warden of St. Thomas' Episcopal Church on West Wheelock Street. He was deeply interested in the life of his church as it touched not only the church throughout the world, but also as it touched the little world of Hanover and Dartmouth College. He was devoted to the country people who worshipped at the little chapel at Beaver Meadow. He gave freely of his time and money there. His generosity and his sensitiveness to human needs never showed more than in the way by which he kept the Beaver Meadow Chapel a living organization through a number of years.

His spiritual life did not allow his own segment of science to become detached from every day reality of human contact and experience. Because of this, his students have received, and do receive, infinitely more than a formal training in Biology. Dartmouth owes a real debt to John Dallas in that his personality and the example of his work affected Doc Griggs so profoundly.

One or two, jeilous of Leland Griggs' hard-bought success, have accused him of being a poseur. They said that the animals were to draw attention to himself and that the shortcake feeds were to buy popularity with the students and that the funny stories were to fill up his classes.

Without doubt, Hanover has had its share of poseurs and exhibitionists. The poseur may carry a beautiful Mauser rifle, but he cannot drop the buck in his tracks at one hundred and fifty yards. The poseur may carry an expensive camera, but he cannot come out of the dark room with a rack of negatives that makes seasoned photographers whistle in admiration. The poseur may lead a big black bear on the leash, but he does not clean out his cage and feed him night and morning. The poseur may serve strawberry shortcake, but his hands are not wrinkled and cracked from dishwashing. The poseur may tell clever little stories to ingratiate himself with his students, but he does not keep open house before final examinations to help any man who will come to him. The poseur may make brilliant laboratory demonstrations, but he does not trudge to that laboratory on bitter cold nights to help men who are behind in their courses and working late.

Leland Griggs' teaching has been as effective outside of the classroom as within its walls, perhaps more so.

He has had his full share of sorrows and disappointments. But essentially he is a most fortunate man. He has done the thing he likes to do the best, in the one place in the world he loves the best.

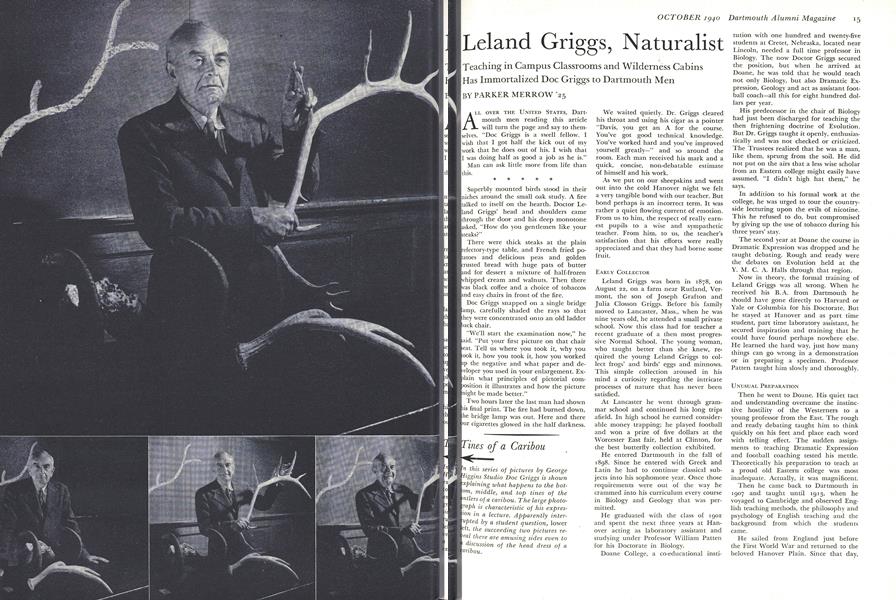

PARKER MERROW '25 Center Ossipee, N. H., editor and publisher, author of Leland Griggs' profile.

Bouchard.

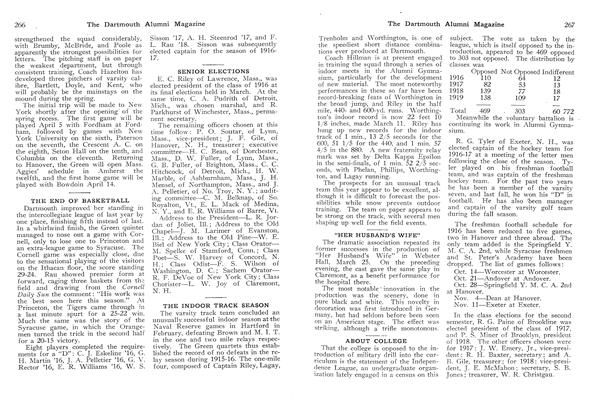

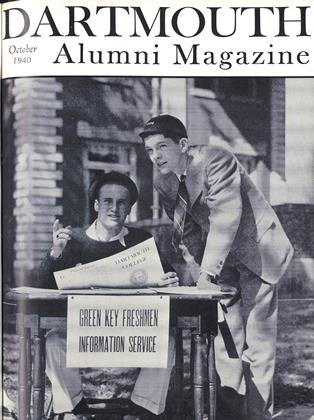

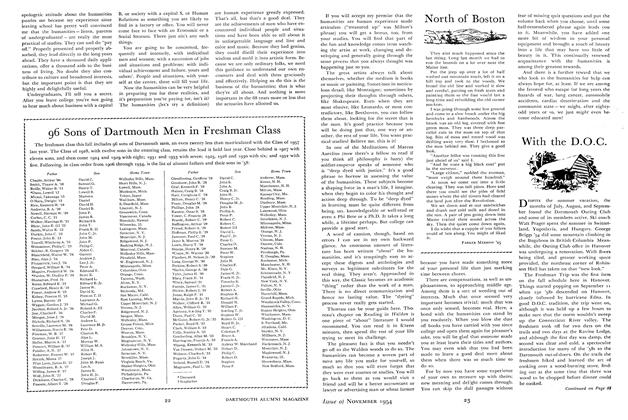

STUDYING NATURAL HISTORY IN NATURE'S SETTING Taking his students in small groups to his cabin at Clark Pond, in Canaan, N. H., DocGriggs teaches informally in effective and pleasant fashion. The outings supplementlectures and laboratory work. Cabin conferences, after supper cooked over an open fire,are often the occasion for discussing books—outside reading required in his courses.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorA Freshman Writes Home

October 1940 -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Article

ArticlePresident Opens 172nd Year

October 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923*

October 1940 By SHERMAN BALDWIN, ROBERT L. MCMILLAN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

October 1940 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ROGER C. WILDE -

Class Notes

Class Notes1931*

October 1940 By CHARLES S. MCALLISTER, CRAIG THORN JR.

PARKER MERROW '25

-

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

February 1947 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

February 1948 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

March 1948 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

December 1949 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

January 1950 By Parker Merrow '25 -

Article

ArticleNorth of Boston

November 1954 By PARKER MERROW '25