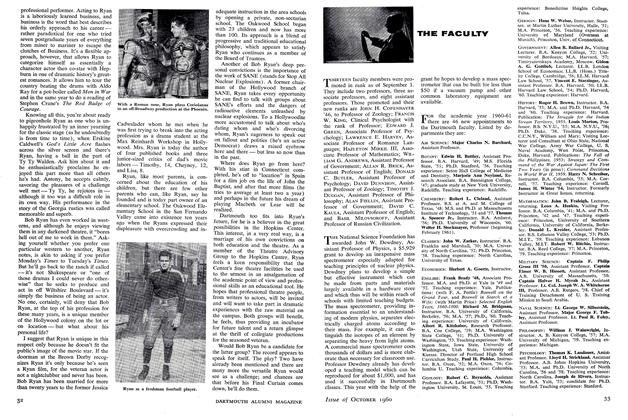

Cannot Parents' Thoughtless Pronouncements Be Mainly Blamed for College Students' Confusion and Cynicism? HUGH LANGDON ELSBREE PROFESSOR OF POLITICAL SCIENCE

THE PROBLEM OF "morale" is not unnaturally uppermost in the minds of many Americans at this time. Although the story of the collapse of France is far too complex to admit of any facile

explanation, most observers are agreed that internal dissension, cynicism, distrust, and defeatism had affected all classes far more deeply than had been realized. As much as anything else, perhaps, a growing awareness of this situation has made

us "morale conscious." We have had recently a barrage of sermonizing and exhortation designed to revive a "fighting faith" in democracy and Americanism.

A generous portion of this barrage has been directed at college students, and at the teachers of the social sciences whom many hold responsible for the attitude of indifference said to exist among the students. Newspaper columnists, college presidents, parents of college students, alumni of collegiate institutions, and many others have repeatedly charged that academic "debunking" and hypercritical teaching have destroyed the faith of students in American institutions and ideals. Even the professors are beginning to take the charge seriously, and nearly everywhere they are scurrying around desperately trying to discover new and better justifications for democracy with which to revive the dying faith of their students.

The argument submitted here is that college professors have had little to do with the declining enthusiasm of college students for democratic institutions and ideals. It would be foolish to deny that there are some students who feel that everything is "propaganda," that one government is practically as bad as another, and that nothing in the present order is north fighting for. The number of such students has probably been fewer than commonly supposed by outsiders, and is un oubtedly declining. It appears'to be ughest relatively in the institutions of the ast and Northeast. What is said here apPlies primarily to student attitudes in those institutions.

For reasons which are discussed later on, it seems to me that the time has come when this entire matter must be handled without gloves. It should be emphasized, however, that this is not a personal attack on Parents, alumni, or any other individuals. It is an attack on certain ideas. Nor is it my purpose to defend the methods or contents of social science courses.

Nor is it to be implied that I agree with those students who think that the people of the United States have no stake in the present international conflict worth fighting for if the need arises. I wish to state unequivocally that I believe it to be in the best interests of the people of the United States that their government should take whatever steps responsible officials may determine necessary to curb the efforts of Germany, Italy and Japan to dominate a large part of the globe.

The charge that student cynicism with regard to democracy in general and American institutions in particular is the result of the "debunking" methods of the social scientists credits college professors with an influence which they do not possess. Most social scientists have learned from experience how slight is the degree of change which teaching can effect in the basic attitudes of their students towards social, economic, and political institutions. Attitude tests provide further confirmation. If there has been a fundamental change in the nature of these attitudes during the past few years, the probabilities are that something far more powerful and shocking than academic "debunking" has brought it about.

There is no mystery about the root causes of the students' perplexity. The past decade has witnessed the most disturbing economic upheaval in our history, and at the present time most of the civilized ]world, as it is called, is engaged in a new and terrible kind of warfare. The unsettling influence of teaching of any kind is puny indeed compared to the influence of these catastrophic events. It might as well be admitted that social scientists have had no great measure of success in preparing the students to face these events. What I wish to point out, however, is that a good share of the responsibility for their failure, and for the cynicism and indifference of the students, belongs to the very people who are doing most of the complaining. If the remarks here are addressed largely to the parents of college students, it should be understood that they are intended to apply with equal or greater force to those who have encouraged the parents to make scapegoats of the professors.

For seven years, during which their sons have been at a far more impressionable age than when they come to college, the parents of most college students have been telling them that the United States is governed by a man who is or wants to be a dictator, that the Constitution has been destroyed, that the government has become totalitarian, and that our most sacred ideals have been trampled in the dust. And yet they cannot understand why some of their sons are slow to see in the present conflict a struggle between two sharply contrasting types of governmental institutions and ideals.

INCONSISTENCY BREEDS CONFUSION

They tell their sons that the less government there is the better, and then invite them to die for their government. They tell them that people should not be allowed to have the kind of government they vote for, and then ask them to go and fight for democracy. They preach a brand of individualism that denies the claims of the mass of individuals, and then expect their sons to be willing to surrender their lives for American individualism. They condemn in the most vigorous language every novel governmental restraint imposed upon them, and then urge their sons to accept cheerfully and even enthusiastically the rigorous discipline of the training camp. They denounce as unjust taxes and borrowing for the benefit of the millions, and then expound to their sons the doctrine of sacrifice.

The wonder is not that a minority of the students are confused and cynical, but that a majority of them still have some faith in democracy.

The elders have firmly implanted in the minds of their children the idea that government is unimportant, generally arbitrary, never to be trusted, and at best a necessary evil. Students are brought up to regard politics as one of the lowest forms of human enterprise and politicians as one of the lowest orders of man. And yet those responsible for giving students these cynical and disillusioning attitudes accuse the social scientists, and especially those social scientists who challenge these ideas most vigorously, of corrupting the political morals of their sons. Parents who almost invariably refer to the current President of the United States in the most derogatory terms accuse the professors of destroying their children's faith in American institutions by pointing out that Abraham Lincoln was sometimes influenced by political considerations. Although their own criticisms of our present governmental system frequently go so far as to say that it has become a totalitarian dictatorship, or is at least about to become one. they claim that the teachers have made their children cynical by pointing out to them that our democracy is in some respects imperfect.

Men who have been making every effort to identify democracy, individualism, and human freedom with the preservation of the existing distribution of wealth, income, and economic control, argue that their sons have been transformed from idealists into materialists by professors who explain that governmental institutions and political ideals are sometimes employed for economic ends. To cap the climax, they accuse their sons and the professors who have corrupted them of intellectual dishonesty.

ORIGIN OF STUDENT ATTITUDES

The influence of the social scientists upon the attitudes of college students is infinitesimal compared to that of the great body of upper middle class people from whom the great majority of the students come and by whom their attitudes are primarily formed. It is not implied that parents should refrain from criticizing the government. Griping is a good old American custom, and the right to indulge in it is one of the things that makes our political ideals worth fighting for. But where men are free to criticize they cannot escape responsibility for their use of that freedom. The kind of criticism that consists in teaching one's children that governments selected by democratic processes and policies overwhelmingly supported by public opinion are Hitlerizing America has boomeranged. Some of the students have become confused. The German government is undemocratic, but so is ours. Why get excited?

The people who did these things did not, of course, mean all that they said. They know full well that there are very significant distinctions between the dictatorship of F. D. R. and that of Hitler. They know equally well that the totalitarianism of the New Deal is not precisely the same thing as the totalitarianism of National Socialism. Now that the issue is drawn, most of them know where they stand and are shocked when their sons appear to waver. Not unnaturally, the college professor is made the scapegoat. The fact of the matter is that these people have cried "wolf" too many times. I agree that there is such a thing as a wolf. In my opinion the cry this time is not just another false alarm. I think that the "everything is propaganda, all governments are just alike" attitude of some of the students blinds them to the existence of dangers that are not at all imaginary. But I can understand how these students came to acquire such an attitude.

After fifteen years of rather intensive effort to give college students some understanding and appreciation of the values of democratic institutions and ideals, I am convinced that little headway can be made in this direction with students who live in an environment in which most of the results of democratic government are regarded with horror. Professors, parents, college presidents, newspaper columnists and platform speakers can teach and preach unceasingly without thereby restoring in such students any real faith in democracy. More than words will be required to counteract the unfortunate and unforeseen effects of the exaggerated laments of many of these people during the past few years. If they really want to revive the students' faith in democratic institutions and ideals they can do so by acting as though they believed in these institutions and ideals themselves.

The most useful service the social scientists can perform, as teachers, is to refuse to abandon, even temporarily, the task of investigating and explaining the working of our institutions. One reason for this is that college students and others need to know all that can be discovered about these institutions, and no amount of preaching and exhorting can give them this knowledge. It should also be emphasized that for the social scientists to execute a right about face and substitute mere glorification of our institutions for analytical treatment of them would make their students more cynical than ever. Our educational ideals would sink to the level of those in Nazi Germany if teachers could not or would not do anything more than urge students to defend democracy. College students would recognize this more readily than anyone else and the effect upon their attitudes would be disastrous.

What can parents, alumni, college presidents, newspaper editors and columnists, and others who have influence with college students do to overcome their cynicism with regard to the defense of American democratic institutions and ideals? It seems to me that the answer is nothing, unless they are willing to modify their own behaviour and refrain from denouncing as un-American and undemocratic every governmental policy of which they disapprove, and unless they are willing also to give up the attempt to identify Americanism and democracy with the preservation of the economic status quo. Cynicism will become more widespread than ever, no matter how many sermons are preached against it, if national defense is found in practice to mean military senice for the youth, high prices for the consumers, low wages and long hours for the workers, and more social, political and economic power than ever for the leaders of industry and finance.

This does not imply that labor, consumers and young men should not be asked to make sacrifices. They will, as a matter of fact, make most of the sacrifices, as is always the case in time of war. But the intensity and effectiveness of their efforts will depend to a great extent upon whether or not they feel that sacrifices are being apportioned equitably and in accordance with democratic processes and ideals. The willingness or unwillingness of parents and others influential with college students to accept decisions involving substantial sacrifices on their part, in terms of privilege and control, will have a decisive effect upon the attitude of the students. Those who expect their sons to be willing to die for democracy ought to be willing themselves to accept its consequences.

Perhaps I should stop here. It is obvious, however, that I have committed the sin of raising in a new form the issue which was discussed in this magazine last year. The charge against the social scientists which I have dealt with here is simply a further indication of the growing suspicion with which parents, alumni, and many others regard their work. It is claimed that they are confusing the students, unsettling their minds, and detaching them from the basic social truths which they have learned at home.

Here again, it is not my purpose to defend the social scientists. Much has been said about their responsibility in dealing with the minds of immature students. I do not belittle that responsibility, nor do I claim that social scientists are doing all that could be done to fulfill it. The pur. pose of this discussion is rather to call attention to the responsibility of those who deal with the minds of these students when they are far more immature than when they come to college.

The student is confused and unsettle long before he comes to college. He aC quires a set of social attitudes from parents. He finds that these attitudes conflict sharply with ideas that are in thealall around him as soon as he gets out the home. He discovers that outside of own circle most people seem to accept these novel ideas. At a fairly early age he is Pre sented with harsh alternatives. If he his ace with his parents and with others in whom he has had confidence, he is atwis with the attitudes which prevail in thecommunity as a whole. If he makes his peace with the community, he is at war with his parents. Usually his choice has been determined before he comes to college. Ipress no opinion as to the factors which determine the choice, nor as to the degreeof disturbance which results and persists. It is a subject which cries for the attentionof the psychologists in our colleges, but ifthey should tackle it boldly what would theparents do?

This confusion arising out of the deep cleavage between the ideas of the parents and the ideas that are in the air intensifiesthe problem of teaching in the socialsciences. The social scientist seeks to assistthe student in the difficult task of learning to make intelligent and realisticchoices in an always imperfect social order.He does this by trying to equip him withan understanding of social institutions andideals. It is customary to belittle the socialscientist's own knowledge of these things.It is limited, of course, but a growing bodyof scholars are giving the lie to the theorythat you cannot subject man and his institutions to scientific scrutiny. An even moreserious limiting factor than lack of knowledge is the absence of motivation on thepart of the student to acquire an understanding of social processes. He wants tofind a justification for the ideas he has embraced. He wants conviction, not knowledge.

This state of mind, arising out of the conflicting social ideas to which the student has been subjected, is not favorable to learning. The student selects from what he hears and reads those facts and ideas which support the attitudes the conflict has left him with, and rejects those that do not. He wants faith. If the faith that he wanted was a faith in the value of knowledge and understanding of social processes, the task of the social scientists would be made easler. As it is, the student is made so uncomfortable by his conflict that he wants Merely emotional satisfaction. He wants to assured that the parental attitudes are right, or he wants to be converted to a new social gospel. The teacher finds that the more emotional he becomes, the more effective he is. The student who rejects the ideas of the parents seems to need this emotional relationship more than the one who clings to them. In either case, however, he is os unstable emotionally that he cannot acquire any real understanding of social Processes.

This raises the most serious problem of all. What do the parents want their sons to get from the social scientists? An understanding of socil institutions and processes, or a set of rationalizations for the "truths" they themselves accept? Is their distrust of the social scientists based upon a feeling that they are not giving their sons an adequate understanding of social institutions, or is it based upon a knowledgethat some of them are teaching things thatconflict with their own ideas of society?

It is impossible to mistake the significance of the rising tide of criticism emanatingfrom parents and alumni. It constitutesa challenge to freedom of inquiry andteaching in the social sciences. Those whoare making the challenge are deeply andsincerely concerned for the welfare of thestudents. They are convinced that whatthey themselves believe is the truth, andthey wish to insulate their children fromany facts or theories which cast doubt onthis truth. In some cases they object to theway in which a topic is treated, and inothers they object to its being treated atall. Always, however, it is done in the nameof protecting the students from disturbinginfluences.

The challenge to freedom of inquiry and teaching in the social sciences cannot be met with a policy of appeasement. Nor can it be condoned because of the good intentions of the challengers. Unless our whole national culture is to reject the ideals of investigation and experimentation, no college which suppresses free inquiry can have any prestige in our society. And if the college loses its standing, the students lose theirs. They cannot expect to become leaders of society, nor even contented members, if they are completely out of touch with the ideals of the society in which they live, and ignorant of its processes.

To be candid, I do not see how one can be optimistic about the future welfare of the liberal college and its students unless parents and alumni take some drastic steps. The first step is to avoid giving their children a set of rigid social attitudes which conflict sharply with those predominant in society and thus unsettle the student so that he cannot profit from a college education. A second step is to make every effort, regardless of the cost, to secure in our colleges a student body more representative of the community as a whole, not merely in the geographical sense, but in an ideological sense. The effect of rigid parental attitudes can be neutralized to some extent if the students are selected in such a way that no single pattern of attitudes is dominant.

Finally, parents and alumni, instead of discouraging their sons from learning and the social scientists from teaching "novel" ideas, ought to do everything in their power to encourage the value of investigation and experimentation. There can be no security in this jumbled world without the fullest understanding we can get of man and his institutions. The student needs values which will give him motivation to be intellectually curious, as well as values which give him motivation for sports and good fellowship. If the parents do not provide this value it may never be acquired. The teachers themselves need a good deal of pushing and prodding, and parents and alumni should insist that they give the best they can.

If the liberal college is to amount to anything in the future, an atmosphere must be created in which investigation and experimentation are regarded by all as necessities, not heresies.

And what if the present trend continues? The parents and alumni could possibly succeed in time in limiting education in the social sciences to recitation of the creeds they considered orthodox. No offense would be given to anyone. Students would be taught only those ideas with which they were familiar at the age of twelve, but they would learn to express them more gracefully and more impressively. We would eventually discover that our liberal colleges had been transformed into glorified boys' finishing schools. The world would have little use for the product, and it is quite conceivable that the admirers of the process would not either.

HUGH LANGDON ELSBREE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

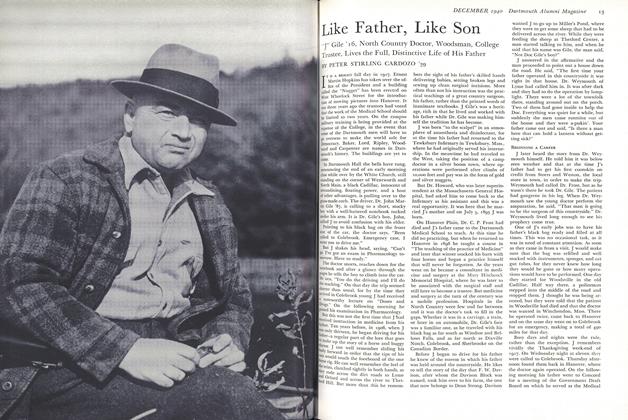

ArticleLike Father, Like Son

December 1940 By PETER STIRLING CARDOZO '39 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1940 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleGreen Eleven Makes Gridiron History

December 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1940 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

December 1940 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ROGER C. WILDE

Article

-

Article

ArticleAMERICAN FIELD SERVICE FELLOWSHIPS IN FRANCE

DECEMBER 1927 -

Article

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

October 1960 -

Article

ArticleCAPITAL GIVING & ENDOWMENT GIFTS

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

July/August 2008 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

ArticleMENTAL HYGIENE LECTURES

April 1931 By Craing Thorn, Jr. -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

April 1947 By HERBERT F. WEST '22