IT IS A BRIGHT fall day in 1917. Ernest Martin Hopkins has taken over the office of the President and a building called the "Nugget" has been erected on West Wheelock Street for the introduction of moving pictures into Hanover. It was three years ago the trustees had voted that the work of the Medical School should be limited to two years. On the campus military training is being provided at the expense of the College, in the event that some of the Dartmouth men will have to go overseas to make the world safe for Democracy. Baker, Lord, Ripley, Woodward and Carpenter are names in Dartmouth's history. The buildings are yet to come.

In Dartmouth Hall the bells have rung, announcing the end of an early morning class while over by the White Church, still standing on the corner of Wentworth and North Main, a black Cadillac, innocent of streamlining, floating power, and a host of other advantages, is pulling over to the grass-made curb. The driver, Dr. John Martin Gile '87, is calling to a short, stocky boy with a well-battered notebook tucked under his arm. It is Dr. Gile's boy, John, called J to avoid confusion with his elder.

Pointing to his black bag on the front seat of the car, the doctor says, "Been called to Colebrook. Emergency case, I want you to drive me."

But J shakes his head, saying, "Can't go. I've got an exam in Pharmacology tomorrow. Have to study."

The doctor snorts, reaches down for the notebook and after a glance through the pages he tells the boy to climb into the car. He says, "You do the driving and I'll do the teaching." On that day the trip seemed shorter than usual, for by the time they armed in Colebrook young J had received a noteworthy lecture on "Doses and rugs. On the following morning he passed his examination in Pharmacology.

But this was not the first time that J had received instruction in medicine from his father. Ten years before, in 1906, when J was only thirteen, he began driving for his to make up the story of a horse and buggy doctor. J can well remember sliding his body forward in order that the tips of his toes would touch the footboard of the one horse rig. He can well remember the feel of the rode across the dirt roads to Lyme and Orford and across the river to Thetford Hill. But more than this he remem bers the sight of his father's skilled hands delivering babies, setting broken legs and sewing up clean surgical incisions. More often than not his instruction was the practical teachings of a great country surgeon, his father, rather than the printed words of inanimate textbooks. J Gile's was a heritage, rich in that he lived and worked with his father while Dr. Gile was making himself the tradition he has become.

J was born "to the scalpel" in an atmosphere of anaesthesia and disinfectant, for at the time his father had returned to the Tewksbury Infirmary in Tewksbury, Mass., where he had originally served his interneship. In the meantime he had traveled to the West, taking the position of a camp doctor in a silver boom town, where operations were performed after climbs of 10,000 feet and pay was in the form of gold and silver nuggets.

But Dr. Howard, who was later superintendent at the Massachusetts General Hospital, had asked him to come back to the Infirmary as his assistant and this was a real opportunity. It was here that he married J's mother and on July 5, 1893 J was born.

On Hanover Plain, Dr. C. P. Frost had died and J's father came to the Dartmouth Medical School to teach. At this time he did no practicing, but when he returned to Hanover in 1896 he taught a course in "The teaching of the practice of Medicine" and later that winter stocked his barn with four horses and began a practice himself that will never be forgotten. As the years went on he became a consultant in medi- cine and surgery at the Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, where he was later to be associated with the surgical staff and still later to become a trustee. But medicine and surgery at the turn of the century was a mobile profession. Hospitals in the North Country were few and far between and it was the doctor's task to fill in the gaps. Whether it was in a carriage, a train, or later in an automobile, Dr. Gile's face was a familiar one, as he traveled with his black bag as far south as Windsor and Bellows Falls, and as far north as Dixville Notch, Colebrook, and Sherbrooke on the Canadian Border.

Before J began to drive for his father he knew of the esteem in which his father was held around the countryside. He likes to tell the story of the day that F. W. Davison, after whom the Davison Block was named, took him over to his farm, the one that now belongs to Dean Strong. Davison wanted J to go up to Miller's Pond, where they were to get some sheep that had to be delivered across the river. While they were feeding the sheep at Thetford Center, a man started talking to him, and when he said that his name was Gile, the man said, "Not Doc Gile's boy?"

J answered in the affirmative and the man proceeded to point out a house down the road. He said, "The first time your father operated in this countryside it was right in that house. Dr. Weymouth of Lyme had called him in. It was after dark and they had to do the operation by lamplight. There were a lot of the townfolk there, standing around out on the porch. Two of them had gone inside to help the Doc. Everything was quiet for a while, but suddenly the men came running out of the house and they were a-pukin'. Your father came out and said, "Is there a man here that can hold a lantern without getting sick?"

BEGINNING A CAREER

J later heard the story from Dr. Weymouth himself. He told him it was below zero weather and that at the time J's father had to get his first coonskin on credit from Storrs and Weston, the local store in town, in order to make the trip. Weymouth had called Dr. Frost, but as he wasn't there he took Dr. Gile. The patient had gangrene in his leg. When Dr. Weymouth saw the young doctor perform the amputation, he said, "That man is going to be the surgeon of this countryside." Dr. Weymouth lived long enough to see his prophecy come true.

One of J's early jobs was to have his father's black bag ready and filled at all times. This was no occasional task, as it was in need of constant attention. As soon as they came in from a visit, J would make sure that the bag was refilled and well stocked with instruments, sponges, and cat gut tubes, for they never knew how long they would be gone or how many operations would have to be performed. One day they started for Woodsville in the old Cadillac. Half way there, a policeman stepped into the middle of the road and stopped them. J thought he was being arrested, but they were told that the patient in Woodsville had died and that the doctor was wanted in Winchendon, Mass. There he operated twice, came back to Hanover and on the same day went on to Colebrook for an emergency, making a total of 490 miles for that day.

Busy days and nights were the rule, rather than the exception. J remembers vividly the Thanksgiving week-end of 1917. On Wednesday night at eleven they were called to Colebrook. Thursday afternoon found them back in Hanover, where the doctor again operated. On the following morning his father went to Concord for a meeting of the Government Draft Board on which he served as the Medical Aid. There were operations scheduled for Saturday morning and that afternoon they drove to Woodsville, getting home at one o'clock in the morning after riding through a snow storm. As they walked in the door, there was a call from Colebrook. The Doctor went to the telephone and said, "We have to get some rest. We'll be there in the morning." At seven on Sunday they started out again, fighting their way through a good foot of snow, to reach Colebrook and perform a major operation on a kitchen table.

While J was still a boy he saw many emergency operations such as strangulated hernias and ruptured appendices. Most of them were performed in the typical, small, low-ceilinged farm houses of the North Country. Milk pans were used to boil the instruments, and kitchen tables or an ironing board stretched between two chairs served as the operating table. Before J entered college he gave his first anaesthesia at a house on Sugar Hill. Today he looks back and wonders how the people dared to give a boy such responsibility. But the modern medical center of today was still a dream, and those were the days of necessity and practicality. In the days before the electric light, J did a lot of "lamp holding" as it was called. He had to stand behind his father and hold up the old-fashioned lamps by their handles. In order to give the most light, the lamp had to be held high over his head. The heavy strain on his young arms often necessitated shifts in position during which time the operation would have to pause. Gritting his teeth, he would say, "Three minutes more," and the doctor would judge accordingly. Ether being heavy, the fumes went downward and this made high holding of the lamp a matter of life and death in more ways than one.

While J was only a senior in college he began to assist his father in operations. Up to this time he had been giving the anaesthesias but now the local doctor would do this and J found himself doing the actual assisting three or four times each week.

And so it was that a boy became a man, that a man became a doctor. There were the liberal arts classes along Dartmouth Row and graduate work "up on the hill," climaxed by two years at the Harvard Medical School, but it takes great living to make a great country doctor and this was found in the surrounding towns of the North Country under the guidance of his father. Today as J Gile steps into the modern surgery of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital to operate, the words experientiadocet must come to his mind, while his thoughts drift backward to water boiling on wood stoves and kitchen tables cleared of their sugar bowls and pumpkin pies.

But there were other experiences, for J Gile was never too busy to be a boy, "the little Gile Boy" as he was known in those days. Again with his father in the role of teacher, he developed his ever-growing love of the out-of-doors. At the age of twelve he made a camping trip with his father to Holeb Lake in Maine which was to be the first of many trips, constituting a major part of his life. A year later we see young J struggling down Main Street, in those days more a continuous mud puddle than a street. One foot is lifted slowly in front of the other, but soon all progress stops and Professor Sherman comes to his rescue, first removing J from the boots and then the boots from the mud. Later, at the age of seventeen, J found his revenge by working as a rod boy for Professor Hazen during the surveying of Main Street in preparation for the first hard-surfaced road to pass through Hanover.

One night, when J was 15 years old, the Gile family held a conference as to the whereabouts of J who had not been seen all day. Since he had not put in an appearance for lunch, his mother thought that he had probably gone down to Mink Brook or out on someone's farm, but when supper was cleared from the table and the sun had long since dropped behind the Vermont hills, she began to feel that he might have run away from home, perhaps to seek his fortune. But J was not far away. It was spring and the Connecticut River was filled with logs that were being sent southward to the mills. J had gone up to First Island where the lumbermen had their camp. There he stayed all day and evening, talking with the men, watching the log drive, and developing his love for the woods and the woodsmen.

The town itself offered little to J in the way of interest. His early life, aside from working with his father, was filled with hours and days and years of pitching hay on the farms around Hanover, riding the races at the Tunbridge "World's Fait' and milking the cows on the Gile Farm which was known as the Grassland Stock Farm. Instead of studying he preferred to be out in the woods, setting traps, or throwing a line into some stream.

Knowing this, Dean Craven Laycock in 1912 wrote a letter to Dr. Gile at my. semester of J's freshman year at Datt. mouth. Knowing that as J sat in class, his eyes wandered out of the window -with thoughts of corn husking and mowing machines, he wrote, "I am pleasantly surprised to find that at mid-semester J is ing all of his courses and may even pas at the end of the year."

In 1916, as a member of Kappa Kappa Kappa and Sphinx, and having been man. ager of the football team, J graduated from Dartmouth. Four years later he received his medical degree from Harvard, after spending the first two medical yean : "up on the hill" in Hanover. During the summer of 1919 for sentimental reasons he I became an undergraduate interne at the Tewksbury Infirmary sleeping in the same room that he had been born in. The years 1930-22 found him interning at the Worcester City Hospital. This period was j climaxed on June 22, 1922 when he married Nettie E. Edmunds, who at the time was a nurse. Returning to Hanover with his bride, J found a place on the surgical staff of the Mary Hitchcock Hospital and was appointed assistant instructor in anatomy at the Medical School.

But 1922 found J's father an old mar. No longer did he travel 25,000 miles in a year on the Boston and Maine and tit Central Vermont Railroads; no longer did farm hands come running to the cry of, "Old Doc Gile's stuck in the mud"; and no longer did emergency calls from Colt brook mean midnight trips over rutted roads. Now it was young Dr. Gile who toot over most of his patients. The need lot traveling had decreased, for since the iff cottage hospitals had sprung up in many of the little towns, but J remembers well a "twenty-five below zero night" in 1923 when he had to use a team of horses tog' through the drifting snow to Woodstock.

In 1925 J's father died. Not only did the College lose a valued trustee, for he had served since 1912; not only did the Medical School lose a beloved Dean, but the to munity, extending from Bellows Falls the Canadian border suffered the loss of a man who had served them tirelessly and faithfully as a friend and as an eminent doctor and surgeon. But to J, himself, the loss was even greater, for his father been his teacher, his companion of the open country, and his guide.

Today, standing in back of J Gile as he operates, one might well mistake him for his father, for physically and temperamenally they are alike. Like father—like son Like his father, he has an undue and al. most unwise pride in his ability to "take ut," to work hour after hour with little or no respite. Like his father, he has two ways of life: the one, medicine, the other, the out-of-doors.

T's excursions in the North Country and New Brunswick can not be put in the same category as the two-week trips that the city businessman takes for relaxation and that "back to the earth" feeling. From his earliest days, J has been a part of that earth and that country. As a boy he fished in Slades Brook, in Mink and Blood Brooks. There were overnight trips with his father to Strafford. Each summer found him in the logging camps of Maine, fishing [or trout and making friends with the guides, the trappers, and the lumberjacks. In the fall his father took him to the Corbin Park Club near Meriden, N. H., where there were 27,000 acres filled with boar and deer and elk to hunt. He and his brother Archie '17 have caught their share of speckled trout on the Magalloway River in Maine. J has also fished the Magalloway with Dr. Kingsford, Professor Murray, Dave Storrs and President Hopkins.

Each summer since 1923 he has taken a trip with Prof. L. F. (Fergie) Murch into the heart of New Brunswick for the big salmon. It is here, in the wilderness, J has responded to another vox clamantis. It is the voice of nature and the people who live with her. It is here that one realizes that J is not only a man who is a doctor, but also a doctor who is a man. Once J crosses the Canadian Border he becomes a woodsman. Through love and respect for the woods he has come to know them. Once he has been over a piece of ground, he knows it as well as the guides themselves. The men of the north are always glad to see him. They like to fish with him, for he realizes that salmon fishing is a brotherhood and that they are all equals in it. Each time that J fishes on the Miramichi, the most famous salmon river, in New Brunswick, he chooses Frank Price for his guide. Not that he needs anyone to guide Mm; there isn't a man in the camp, including the cook, with whom he couldn't trade places. But there is more to salmon fishing than rods and reels. There is a spirit of companionship and of working together. There is no way to join the rotherhood. One is either in it naturally Mhe isn't; J is a life member.

Cains River, Renous, Rocky Brook, and Dungarvon are some of the tributaries of the Miramichi. In 1927 they were in the wilderness of New Brunswick. J Gile was "the first man to go into lots of those places" according to noe of the local persons. He may not catch the largest salmon every year, but he has caught something else, the love and respect of the people. Whether it is salmon fishing with Frank Price or the making of a sway bar or a goose neck for the logging sleds with the local blacksmith, he can talk to them in their own language and he knows what he is talking about.

In the evenings he likes to smoke his pipe and sit around the fire talking with the guides about the river and the woods, and the old timers who trapped and fished throughout the country. But whether it is in the hospital or up on the Miramichi, J likes to crowd a lot of life into a single day. Once he hooked a salmon on a light line and took four hours to land him. When he got back to the camp it was eleven o'clock and George Allen said, "We get home at eleven, but, sure as shooting, the doctor will get me up at three in the morning to begin all over again."

On one trip he decided to go up to the camp at Rocky Brook. Harvey Scott, one of the backwoodsmen who drove the "tote" wagon, had retired the year before because of old age, and his sons had taken over the job, but when he heard that J was coming up again for the fishing, he said, "By the jumpin' Lazarus, if the doctor is going in, I'm going to drive him."

And then there was the year of '35 when J arrived too early in the spring for the fishing. The ice had just gone out and the water was still high. The drivers were on the river, putting in logs from a landing and driving them down stream. J grabbed a peavy and started driving the logs with the rest of the men. Notwithstanding a ducking in the cold water, he kept on driving until the salmon began to run.

One day while they were fishing, J noticed that the shell drakes were eating the small salmon. He asked Frank Price if the ducks were good to eat. Frank nodded his head and said that they were "if you know how to cook them." Frank gave J the recipe: "Put a pot of water on the stove. As it begins to boil drop the duck in alonig with a stone as large as your fist. When you can put a fork through the stone, the duck is ready to eat."

But J's home is still New Hampshire and it is this country he knows best. Today as Life Trustee of the College his knowledge of the North Country and more specifically the Second College Grant makes him nearly irreplaceable as an adviser on those timber land investments.

J's TRUSTEE TRAINING

When one speaks of J Gile as a trustee we must remember that his father was one before him. We must remember that his father was too busy to take time off for meetings and that when men like Nichols and Hopkins and Halsey Edgerton wanted a conference with him, he would say, "I have to go to Colebrook. Hop in and we'll talk. J will drive us." J had learned that young boys should be seen and not heard and there is little doubt that it was on such trips as these that he received his initial training for the duties of a trustee of the college to which he is devoted.

A few years ago, when Kenneth Roberts paid a visit to the campus he talked to and argued with J Gile concerning some factual matter dealing with the North Country in one of the author's latest books. Today there is a message written across the title page of J's copy of Northwest Passage. It reads as follows: "Inscribed for Dr. John F. Gile who knows Rogers' country better than I do, with the very best wishes of Kenneth Roberts."

The College Grant is a second home to J, for he has been going there since he was a boy. It is here that he re-established contacts with such men as Old Buckman, Jack Haley, George Allen and the other old characters that his father knew. It is here that he becomes a woodsman, talking to the New Hampshire folk, working with them as they cruise the timber for best cuttings, and in all serving as a real and human link between the College and its holdings. There is serious work, but there is always good-natured humour. Each year when J went to Peaks Camp in the Grant he held an almost traditional dialogue with Jim Cilley who was one of the fire wardens: J: Wonder why no one knows how large the upper college farm is? Jim: Why, I know. Chained it myself. J: You do? Jim: Yes, sir. It's just 10 and twelvetenths acres.

When J tells his tales of the North Country he is no longer the well-dressed surgeon of the medical center; instead he takes the part of the woodsmen themselves. He uses the dialect, the language and the inflection, but he is not an actor taking a part, for J Gile has two hearts: one of them is in his work and life in Hanover, the other is in the woods.

His work in Hanover, since that day in 1982 when he was appointed as an assistant instructor in the Medical School, has progressed by hard work and perseverance. Since then he has held the title of instructor in Physical Diagnosis, instructor in Anatomy and now holds the chair of professor of Clinical Surgery.

In 1927 he was one of several doctors who formed the Hitchcock Clinic which today has helped to make the Medical Center of which Hanover may proudly boast. The Clinic is one of the very few examples of this modern type of medical organization in the eastern part of the United States. It is composed of physicians and surgeons, who carry on their practice cooperatively, using common offices and professional equipment in the Hospital building, and having a joint business administration.

J has the usual trait of all medical men o£ not talking about his work. In Hanover, however, he lives, eats and sleeps for his work at the Hospital. He does not romanticize his profession. He exudes none of the Men in White atmosphere. It is all hard work which he does quietly, skillfully, and expeditiously. Today he is acknowledged to be one of the finest surgeons in New England.

But the man Gile overshadows the sur- geon. Listening hard, but saying little, he has a typical Yankee make-up. Although he belongs to the school of Stoics and the Spartans, there is great kindliness under his practical atmosphere of ruggedness.

As a doctor he is informal in approach and interested in the personality of people. He would be lost in a Park Avenue practice for here he and his patients are cut from the same cloth of homeliness, and here he has as his friends the real North Country woodsmen, whose daily life is bred of homely courage.

From traveling with his father, he developed the habit of long hours of work, but three-fourths of those days were spent in going from one town to another. Today J puts in as much time, but it is all medical work. On Sundays he likes to take his family for a drive along the same roads on which he drove the horses and the old Cadillacs as a boy. Riding from Hanover to Colebrook, he will reminisce, "There isn't an hour out of the twenty-four that I haven't been on some part of this road" whereupon his children, John Jr., jane Amos, and Nancy will say, "He's off again." And it is these children who lead him to say that he has never had any identity of his own. "In the old days, I was known as 'Doc Gile's boy' and today peopie say, 'Oh, you're Jack's (or Amos') father.' But J Gile does have a very real identity of his own. He is a teacher, trustee, surgeon, woodsman, but above all a man. Today, at 48, he has become his father's son, serving that same large community as doctor, surgeon, and friend Richard Hovey might well have said of J Gile, "He has the still North in his sou], the hillwinds in his breath; and the granite of New Hampshire is made part of him till death."

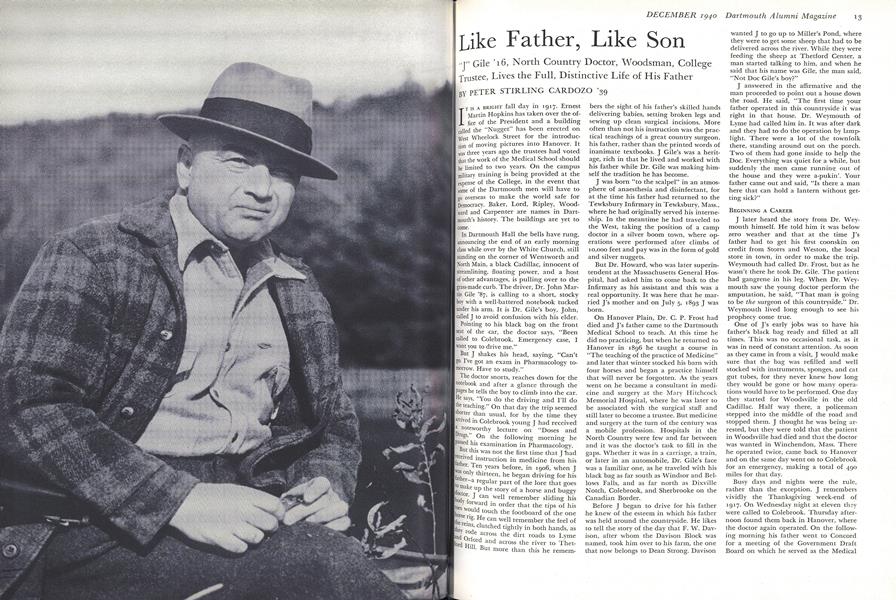

JOHN M. GILE '87Onetime Trustee of Dartmouth Collegeand North Country Physician.

THE GILE BROTHERS Archie '17 and John '16, in UndergraduateRegalia During the Winter of 1915-16.

DR. GILE AND DR. JOHN P. BOWLER, NOTED SURGICAL TEAM OF THE HITCHCOCK HOSPITAL

"j" Gile '16, North Country Doctor, Woodsman, College Trustee, Lives the Full, Distinctive Life of His Father

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleAmerican Student Morale

December 1940 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1940 By Charles Bolte '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

December 1940 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, DONALD BROOKS -

Article

ArticleGreen Eleven Makes Gridiron History

December 1940 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935*

December 1940 By JOHN D. GILCHRIST JR., BOBB CHANEY -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

December 1940 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ROGER C. WILDE

Article

-

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

DECEMBER 1981 -

Article

ArticleMasthead

JAN.- FEB. 1982 -

Article

ArticleHood Director Named

MAY 1985 -

Article

ArticleWinter Carnival

February 1951 By C. E. W. -

Article

ArticleSHOULD THE NEW GRADUATION TRADITION OF SMASHING CLAY MUGS BE DROPPED? IF SO, WHAT SHOULD REPLACE IT?

September 1993 By kai Singer '95 -

Article

ArticleThayer School

May 1948 By William P. Kimball '29