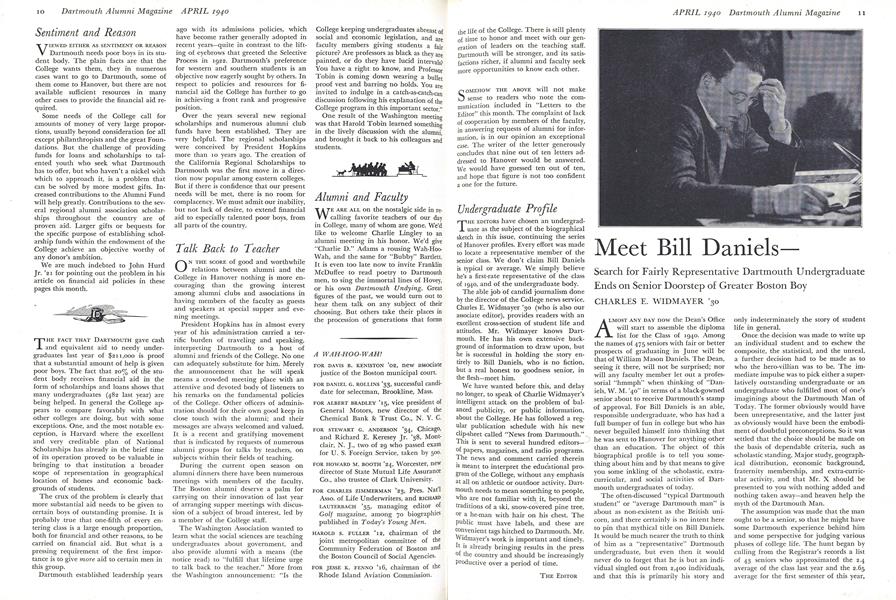

Search for Fairly Representative Dartmouth Undergraduate Ends on Senior Doorstep of Greater Boston Boy

ALMOST ANY DAY now the Dean's Office will start to assemble the diploma list for the Class of 1940. Among the names of 475 seniors with fair or better prospects of graduating in June will be that of William Mason Daniels. The Dean, seeing it there, will not be surprised; nor will any faculty member let out a professorial "hmmph" when thinking of "Daniels, W. M. '40" in terms of a black-gowned senior about to receive Dartmouth's stamp of approval. For Bill Daniels is an able, responsible undergraduate, who has had a full bumper of fun in college but who has never beguiled himself into thinking that he was sent to Hanover for anything other than an education. The object of this biographical profile is to tell you something about him and by that means to give you some inkling of the scholastic, extracurricular, and social activities of Dartmouth undergraduates of today.

The often-discussed "typical Dartmouth student" or "average Dartmouth man" is about as non-existent as the British unicorn, and there certainly is no intent here to pin that mythical title on Bill Daniels. It would be much nearer the truth to think of him as a "representative" Dartmouth undergraduate, but even then it would never do to forget that he is but an individual singled out from 2,400 individuals, and that this is primarily his story and only indeterminately the story of student life in general.

Once the decision was made to write up an individual student and to eschew the composite, the statistical, and the unreal, a further decision had to be made as to who the hero-villian was to be. The immediate impulse was to pick either a superlatively outstanding undergraduate or an undergraduate who fulfilled most of one's imaginings about the Dartmouth Man of Today. The former obviously would have been unrepresentative, and the latter just as obviously would have been the embodiment of doubtful preconceptions. So it was settled that the choice should be made on the basis of dependable criteria, such as scholastic standing, Major study, geographical distribution, economic background, fraternity membership, and extra-curricular activity, and that Mr. X should be presented to you with nothing added and nothing taken away—and heaven help the myth of the Dartmouth Man.

The assumption was made that the man ought to be a senior, so that he might have some Dartmouth experience behind him and some perspective for judging various phases of college life. The hunt began by culling from the Registrar's records a list of 4.3 seniors who approximated the 2.4 average of the class last year and the 2.65 average for the first semester of this year, who came from the New York-Massachusetts-New Jersey-Connecticut area from which the majority of Dartmouth students come, and who majored in the social sciences or in English, the fields chosen by better than 60 per cent of the class. It was apparent at once that no paragon of all the standards was going to come to light, so the process of elimination began. Fraternity membership (two-thirds of the class belong) and some extra-curricular activity were deemed necessary criteria, and when measured against these the list of possibilities shrank to 18 men. By checking economic background and refining the fraternity criterion to the extent of accepting only a house in the middle group, it was possible to boil the list down to seven. From there on it was necessary to split hairs about preparatory schools and all the standards that had already been gone through. The list grew smaller and smaller until two men were left. A coin finally settled it, and Mr. X took on the identity of Bill Daniels of Newtonville, Massachusetts, Greater Boston boy, Newton High School graduate, C-plus student, social science major, Sigma Chi member, thirdline hockey player, and varsity tennis manager.

HAS POSITIVE QUALITIES Bill is a personable, dark-haired senior who reached voting age last August. He possesses an aura of good health and a .sturdy frame, standing 5 feet 10 inches and weighing 165 pounds, and one's first glance associates him with athletics rather than the classroom. When he puts on his glasses, as he does fairly regularly, he looks more like the student his marks prove him to be; and when he talks to you he expresses himself concisely and well, belying the struggle that he underwent to pass freshman English. He is, in brief, a positive sort of person, impressing you first with masculine qualities and then making you aware that he has social poise and, as his classmates would put it, "something on the ball."

Bill is the only son of Mr. and Mrs. William Albert Daniels, who reside at 57 Oakwood Road in Newtonville. His one sister finishes high school this year and next fall starts a junior college course at Edgewood Park in Briarcliff Manor, N. Y. Mr. Daniels, who is purchasing director for the Farrington Manufacturing Company in Boston, is not a college man, but Bill was early subjected to the Harvard influence through his grandfather and uncle on his mother's side. It was rather taken for granted in the family that Bill would go to Harvard, but before he reached high school he began to make up his mind that he wanted to enter Dartmouth. This met with approval in the Daniels household, for some of the family's closest friends are Dartmouth men, among them Chester C. Butts 'll and Mr. Daniels' business associate and neighbor, Harold H. Lounsberry '15, who has the further distinction of being Dean Strong's brother-in-law.

The pre-medical preparation offered at Dartmouth was what appealed most to Bill, for at that point he had his heart set on becoming a good doctor. He took to all his science courses in high school and as an "A" student in mathematics was bright enough in that subject to earn some college money by tutoring. His general scholastic record at Newton High was excellent, except for "C" in English and Latin, and he was elected to the National Honor Society in the spring of 1936. Bill was also a good high-school athlete, playing firststring center on the hockey team for two years, and winning his letter as quarterback on the football team. His interest in golf gave him another chance to earn money toward his college expenses, and for seven summers throughout high school and college he has had the job of caddy master at Hotel Wentworth-by-the-Sea near Portsmouth, N. H. Other high school honors went to Bill as vice president of the junior class, member of the Athletic Board, member of the Legislature and Executive Council, and member of the Senior Prom Committee.

This was the all-round record that Bill Daniels presented to Dean Strong when he applied for admission to Dartmouth. He had been so worried about the "C" in Latin that he had earlier taken and passed a College Board exam in that subject. As part of the Selective Process machinery Dean Strong also received a rating from Principal Elicker of Newton High School, a personal rating from an alumnus, in this case Mr. Butts, and a rating from the Alumni Council interviewing committee, which consisted of Frederick H. Caswell '23, Robert D. Salinger '26, and Carl F. Schipper Jr. '26. The ratings were high, Bill stood within the top quarter scholastically of a class of 650, his high school was fully accredited by Dartmouth, and there was evidence of intelligence, character and personality. He was graded an A-i prospect and admitted in the first of Dean Strong's many sittings of the application list.

So Bill Daniels came to Dartmouth and added the class numerals '40 after his name.

He began his college studies by electing Chemistry, Mathematics, and German, in addition to English and the required course in Social Science, which supplanted Citizenship and Evolution when the Class of 1940 entered college. An "A" in Math and "B" in Chemistry offset "D's" in Eng. lish and Social Science, and Bill finished his first semester with a 2.2 average. The second semester of freshman year he boosted his standing to 2.4 as the result of a "B" in Social Science, but English continued to get him down and the minimum passing grade was again the best he could do. "I never could get the hang of big words or see the sense of poetry" is the way Bill summarizes his adventures with the mother tongue.

Sophomore year Bill carried a sixth course in laboratory Physics that was required for entrance to the Medical School and also elected Professor Hull's Physics 3. He continued his Chemistry and German, elected Botany 1, and chose Political Science 1 for his Social Science requirement. The extra subject and the customary sophomore slump combined to give him six "C's" and a flat 2.0 average for the first semester. Zoology followed Botany and Economics took the place of Political Science for the second half of the year, while the other four courses continued for the full year.

LOSES TASTE FOR MEDICAL CAREER Two important things happened to Bill, the student, during the second semester of sophomore year. He found that he had no taste for the highly specialized study that a medical Career would require, and at the same time he discovered a predilection for Economics, in which he received an "A" for the term. The choice of a Major field had to be made in the spring, and Bill elected to drop medicine and devote the specialized study of junior and senior years to one of the four newly introduced Topical Majors. His choice was "National Problems—Social and Economic." His top grade in Economics and a "B" in Chemistry pulled his four "C's" up to 2.5 for the best average of his first two years in college.

The main objective behind the Topical Majors, introduced by the Class of 1940, is integration—the pursuit of a subject, such as Bill's "National Problems," across departmental lines. Having chosen National Problems or International Relations or Democratic Institutions or Local Institutions and Problems, the junior is given a listing of interrelated courses in Economics, Sociology, Political Science and History from which to map out a two-year program of study. Two courses each semester of junior year and four courses each semester of senior year are required, as are the prerequisites of Economics 1, Political Science 1, and Sociology 1. Bill lacked the last of these prerequisites, but got permission to take Sociology 1 the first semester of junior year.

After a year and a half of Topical Major III, Bill doesn't feel that he has managed to integrate his field at all. Instead of majoring in Economics, as he would have under the departmental system, and instead of having a pretty thorough knowledge of that one field, he does have a more general appreciation of national problems from the economic, political and social viewpoints. But the actual fusion of separate courses into something approximating a cohesive whole has been left up to him without success. Students taking a departmental Major in the social sciences have a coordinating course and a senior thesis which help to pull things together. Bill would like something similar in the Topical Majors, but realizes that the breadth of his field and the departmental character of the faculty make it difficult.

During the past year and a half Bill's Major study has covered Corporations and Trusts, National Administration, Economic Reform, Social Trends, Labor Problems and Labor History, International Trade, Public Opinion and Propaganda, and Criminology. This semester he is taking Banking Institutions, Public Finance, Conflicts in Modern Civilization, and Social Maladjustment. To round out his junior year he elected elementary Psychology and Public Speaking, and took a year course in organic Chemistry under Professor Bolser. Last semester his outside course was the psychology of Advertising, and at present he is studying the Principles of Accounting, a special Economics course open only to seniors.

Bill opened his junior year with 2.4, fell off to 2.0 in the second semester, and came back with a new high of 3.0 last term. That gives him a seven-semester average of 2.35, which is just about the average for the entire College each year. He has it in him to do a lot better scholastically than he has done, and if he were going into a graduate school where he really had to apply himself, the chances are that he would do extremely well. As it is, he has learned that the secret of academic success is to keep up with the assignments from day to day, putting on a little extra pressure for hour exams, and mapping out a definite program of reviewing and cramming for final exams. This has earned him a "C" or better in every course since freshman year and has allowed him plenty of time for hockey, his managerial duties, and social life with his college friends. Studying averages about two or three hours a day, except at exam time, and whenever possible Bill does his assignments at the Library, where there is least distraction.

For the profs he likes Bill is willing to put forth some extra effort. He is convinced that the way in which the course material is presented has a great deal to do with the student's interest and desire to work. During his four years at Dartmouth he hasn't struck up a close friendship with any member of the faculty, but there are a number of professors of whom he will have fond and vivid memories in the years to come. Professor Keir is one of his great favorites, and Bill gets impressed all over again when he tells how the class in Labor Problems once insisted that the professor keep on lecturing and give up the idea of dismissing it for a football rally. His liking for college Chemistry is inextricably bound up with the brisk character of Professor Bolser. The faculty as a whole knows its stuff, Bill would summarize, but it is only where the professor's exceptional personality gets fused with the subject that a course becomes alive and exciting.

LEARNS OUTSIDE CLASSROOM TOO

Bill figures that during the course of four years at Dartmouth he has learned a lot that had no connection at all with courses or professors. His education outside the curriculum has centered around the daily contacts, discussions and bull-sessions with fellow students. Outside reading of a literary or serious nature has not been one of his virtues; he would rather read a magazine like Collier's for entertainment or "bull" with his roommates and friends about almost any subject under the sun. Sex, religion, politics, and the European war seem to be the major topics for bullsessions these days—which introduces only one new topic over the old days. The paradox is that students discuss religion but are seen in chapel or church only in small numbers. Bill went to chapel once for an Armistice Day service, and entered the White Church one Easter Sunday that happened to fall before spring vacation. Outside of class work he doesn't make any special effort to keep up with current events, although he reads The BostonHerald regularly and occasionally sees the New York papers. Lectures by visitors to the College have no appeal to him, unless the speaker happens to be a world celebrity, in which case he is usually among the great jam of persons who cause the lecture to be transferred hastily from Dartmouth Hall to Webster. He has never subscribed to the Concert Series, although he has attended single concerts by the Boston Symphony Orchestra and Kirsten Flagstad. "I like opera singers and symphony orchestras," Bill asserts, "but violinists and pianists and things like that get me down." As for dramatic presentations on the campus, he has yet to see one.

Bill's fraternity brothers and other friends come from all over the country, and he backs up Dartmouth's admissions theory with the belief that he has learned a lot and has gained a broader view through his relations with men from widely separated sections of the nation. This is one of the most interesting and valuable aspects of student life in Hanover, Bill thinks, but he has one reservation to make. "After rooming with Jack Chisholm for two years I never want to hear another word about Minnesota or about Duluth in particular." A Minnesotan in the room would seem to be a good balancing influence, however, for Bill's two other roommates come from Auburndale, Mass., and Springfield, Mass., and a fifth member of the group last year came from West Hartford, Conn. Bill hasn't had much experience with the economic distribution of the student body. He has no close friends who are working their way through college, and it is usually hard to tell whether a fellow is getting financial aid from the College. Like Bill himself, most of his friends are not on scholarship but are working summers and are spending not much more than the minimum amount needed each college year.

Summing up the educational influences of the College, both in and out of the classroom, Bill feels that Dartmouth has given him what he came to college to get—taking into account that he lost the ambition to study medicine and turned instead to a Topical Major largely of Economics and Sociology and to a probable career in the business world. He will not go out of college a specialist in any one field, but he likes his general outlook and the broad cultural background that he has to build on, and he has no fear of not being able to adjust himself to the demands of a particular job. "That's the whole idea of a liberal arts education, isn't it?", Bill asks, with some show of knowing what Dartmouth is all about.

ATHLETIC RECORD BEYOND EXPECTATIONS While it is perhaps fair to say that Bill hasn't fully realized his possibilities as a student, he has done well in extra-curricular activities. In athletics, in fact, he has gone beyond expectations and has a good chance to get his hockey letter this year. As high school athletes go, he was versatile aad fairly prominent in the Greater Boston area, but the pace of college athletics was always a bit beyond him. Bill knew that college football as played at Dartmouth was too demanding for him, so he concentrated his efforts on hockey, which had always been his best sport. He reported to Coach Herb Gill for freshman hockey and earned his numerals as center on the second line. As a sophomore he was a member of the first varsity squad coached by Ed Jeremiah, for whose coaching skill and hilarious sense of humor he has high praise. Bill was relegated to the fourth line of a championship team that boasted such centers and wings as Dave Walsh, Bud Foster, Fud Mather, Dick Lewis, Dan Sullivan, and Junie Merriam. "What it amounted to," he says, "is that I was out for the practice."

In his junior year a bad case of grippe kept Bill at home from Thanksgiving until Christmas, and he did not report for hockey. This past season, however, he was back as a varsity candidate and saw a fair amount of action as center on the third line. For the final game of the season he went along to Princeton as a spare for the first two lines, and when Fred Maloon was injured shortly after the game started he got his big chance by filling in as first-line center. A minute and a half after he entered the game Bill scored Dartmouth's only goal on a pass from Pidge Hughes undoubtedly the high point of his hockey career. The contest soon took on an all- Princeton complexion, but Bill finished out the game in competent fashion, and although he hasn't played the required total of sixty minutes in league competition, the chances are that he will be recommended for a letter by Coach Jeremiah.

[Ed. Note: Coach Jeremiah did recommend him and the letter was awarded.]

From Bill's point of view, athletics in college have been thoroughly worthwhile and he has no regrets about the long hours given over to practice. During the winter season his studies have taken something of a beating, he admits, but at all times he has managed to remain primarily a student and only incidentally an athlete. The idea that athletics have real educational value in a liberal arts college isn't at all farfetched, Bill maintains. He is certain that his hockey experience at Dartmouth will have more lasting influence than some of the courses he took, and he is grateful for the friendships which being a team member has made possible for him. It follows naturally that he doesn't subscribe to the belief that athletics are over-emphasized at Dartmouth, although he feels that there might be just a little justification for believing that about football. Bill's knowledge of the inner workings of the Athletic Council makes him realize, however, that football has to carry the whole athletic works, and he doesn't know of any way to curtail the sport without curtailing the whole athletic program, which seems none too large at present.

Intramural athletics have not been among Bill's activities, mainly because of the restrictions on freshman and varsity squad members. Also, the combination of hockey and managerial duties has given him a fairly heavy schedule of outside work, which is a reason why he has skipped not only intramurals but also other campus activities. Bill has an inclination to give himself over to one thing at a time, on top of which he has taken some pains to save room for the general social life he likes so well. Since he gets in a great deal of golf during the summer, he has not bothered to play the game at college, but he has taken up squash since coming to Dartmouth and looks upon it as a sport that will combine with golf to keep him in trim after graduation.

As a member of the Class of 1940, Bill was involved in a number of scholastic innovations, and a change in the managerialcompetition system in his freshman year fortunately enabled him to swing both hockey and the competition without conflict. Managerial candidates formerly heeled from April to April, and when it was decided to have the period run instead from December to December, Bill's competition had to prepare the way by heeling for only half a year, from April of freshman year to December of sophomore year. Award of the tennis managership also made it possible to keep on with hockey after that.

As a heeler Bill went through the wellknown mill of lugging equipment, cleaning football shoes, retrieving foul balls, dashing out with water buckets, and working in the D. C. A. C. office. He found it fun as well as hard work, and although he didn't get one of the Council's top managerial awards, he stood well in his competition and earned himself a reputation for dependability. As assistant manager, Bill handled a good deal of the routine work for varsity tennis and looked after the freshman team while the manager accompanied the varsity on its out-of-town trips. This spring he will manage the varsity through a schedule that he largely arranged many months ago, while his assistant learns the ropes through detail work and oversight of the freshman team. Major reward for the tennis manager is the southern trip of spring vacation, which Bill will be enjoying when this issue of the MAGAZINE appears.

A BLOW TO THE MYTH At this point in our consideration of Bill's outside activities it is necessary to deliver a body-blow to the myth of the Dartmouth Man. He simply does not ski; in fact, he is a bit fed up with everyone's blithe assumption that he does. The myth preserves a remnant of self-respect in the fact that he went skiing twice in his sophomore year, fate bringing him a Carnival date who more or less insisted upon it; but left to his own devices, he will not be found on the Oak Hill tramway. Further consolation is afforded the die-hards by Bill's statement that "Coach Jeremiah wouldn't have let us hockey players ski if we wanted to." Perhaps hockey is the villain in the piece, but one will never know.

Although Bill hasn't indulged in skiing, cabin trips, hiking, or outdoor life of that sort, he has a goodly number of friends who like and participate in that aspect of Dartmouth life. He is perfectly willing to concede the virtues of such activities, for others, and will even go so far as to agree with the senior vote that the Dartmouth Outing Club is the organization doing the most for Dartmouth, but the great out-ofdoors has never wooed him away from the great indoors.

The main base of indoor operations this year is the Sigma Chi house, where Bill iS resident house manager. The fraternity Is now inevitably the center of his social life, but this was not the case before he moved into the house for the first time last fall. Bill roomed off-campus last year with four other '40 men—Gordon Wentworth, Jack Chisholm, Kenneth Steele, his present three roommates, and Sidney McPhersonand at that time 17 West Wheelock Street was just as inevitably the base of social activity. During sophomore and freshman years he roomed at 313 New Hampshire Hall with Gordon Wentworth and found most of his free time spent with dormitory friends. Except for men living at the house and for some exceptional individuals, a fraternity does not play anywhere near a monopolizing role in the social life of its members, Bill believes on the strength of his own experience. Even though he has roomed almost entirely with fraternity brothers and counts them his closest friends, he has other friends outside his own house, mainly as a result of hockey and the managerial competition, and has at least one close friend who has not joined any fraternity.

HAS HAD FIVE HOUSEPARTY DATES

"Houseparties, of course, are different," Bill adds. "For big week-ends like that the fraternity becomes the center of things, especially when you've paid your houseparty tax." Out of fourteen party weekends since he has been at Dartmouth he has had girls up to Hanover for five of them. Green Key Week-end is Bill's favorite party, so the chances are that he will bring the final total to six before graduating. Carnival is fun and has not grown too big to spoil the students' enjoyment of it, in Bill's opinion, but he holds out for Green Key weather, picnics, and big-name bands. Houseparties, except the Carnival party when he is in training for hockey, provide the rare occasions when Bill drinks anything stronger than beer. The latter is his preference for Saturday night get-togethers at the house and the few other times when he feels independently inclined to swell the coffers of the Tanzi Brothers, dealers par excellence in fruit and creamy ale.

Bill's duties as house manager this year consist mainly of running the houseparties and seeing that there are sufficient pingpong balls and electric-light bulbs. There's really more to it than that, but that is the way in which he dismisses his responsibility as general overseer. To one talking with Bill about fraternity life it is obvious that he likes it but that he hasn't gone overboard about it. A fraternity seems to be iargely a social outlet for him, and it would be impossible to get him to argue strenuously about national affiliation or any kindred topic. Bill thinks that belongIng to a national has the good, practical advantage of providing a port of call at other colleges, but he's not sure that this is worth the extra cost.

If he were in a national or a local house, Bill wouldn't mind so long as there were some good bridge players there with him. Bridge is a favorite diversion of his, and when the studies are out of the way—sometimes when they aren't—he can be found in happy concentration at a card table with three of the brethren. Bridge, bull sessions, magazines, and dance records (Bill likes the "sweet" kind) are the likeliest forms of relaxation at the house. Once or twice a week Bill goes to the Nugget, depending on the number of good shows. He usually sees the first show at night, going to the theater right after supper and getting out at 8:30 in time to finish up an assignment or two before bedtime. He relies heavily on the reports of afternoon Nugget-goers, for the movies don't attract him unless they are worth seeing. "Heard anything about the show?" is always a good conversational opening in Hanover, and if favorable reports circulate, the first show at night is likely to be a mob scene. Bill can beat this by getting ahead of the 6 o'clock supper rush on Main Street. He has been eating around ever since freshman commons and a sophomore period at Ma Smalley's eating club, and at present he is back on Main Street after sticking to Thayer Hall for nearly a year. Bill and the fellows he usually eats with like variety, and they consequently make the "grand tour" of favorite restaurants during the course of a college year.

Bill has no car, but when he occasionally plans a week-end trip away from Hanover in the fall or spring he can invariably arrange for transportation in one of the 350 student-registered cars—a fleet which grows closer to 500 when students return from spring vacation. These week-ends are usually spent in Boston, with headquarters at home. Bill has been taking infrequent week-ends since freshman year, and feels that for anyone at Dartmouth who enjoys feminine company, dancing, and metropolitan entertainment it is necessary to get away from time to time. He has never had a date up to Hanover except at houseparty time. In respect to lack of feminine company and of things to do on the ordinary week-end, Dartmouth's north country location is a social disadvantage, Bill thinks. On the masculine side, however, he is all for the solidarity of spirit and the informal life made possible by the College's comparative isolation. As far as dress is concerned, Bill is only a little less formal than he would be at an urban college. He never effects the outdoor mode, which is symbolized by a plaid shirt-tail hanging out, but sticks to neckties, sport coat, slacks, sweaters, and an occasional regular suit. Weekends call for the "smoothest" items in one's wardrobe, with tails carried along for college proms or the extra-special date.

This discussion of week-ends is probably misleading you, for Bill certainly gives them no great amount of time. They are interesting mainly as a form of escape from Hanover's ultra-masculine atmosphere and as a fairly prevalent indulgence by most students who can afford them. It would scarcely be possible for week-ends to loom large in Bill's view of college, what with the studying necessary to maintain last semester's 3.0 average, the hustle involved in making the hockey team and managing varsity tennis, and the preoccupation with the assembly of good friends around him throughout the year.

In a comparatively short time Bill will have come to the end of the four years on Hanover Plain that will always be a period apart in his life and thoughts. Like most Dartmouth men who have gone before him, he is finding his senior year the best and most significant of his college course. Just what of lasting value he is going to take away with him when he leaves Hanover is difficult for anyone but Bill himself to say. He feels at the moment that he will need both time and perspective to tell what Dartmouth has really meant to him. And although he has had a good deal of contact with Dartmouth graduates, he will need both time and perspective to find the full answer to what it means to be an alumnus of the College. At the moment, however, these are unimportant considerations, for Bill's is the happy lot of being completely engrossed in the work and fun of being a Dartmouth undergraduate —an experience singularly unchanged from that of generations past, despite all the modern characteristics of the Dartmouth Man of Today.

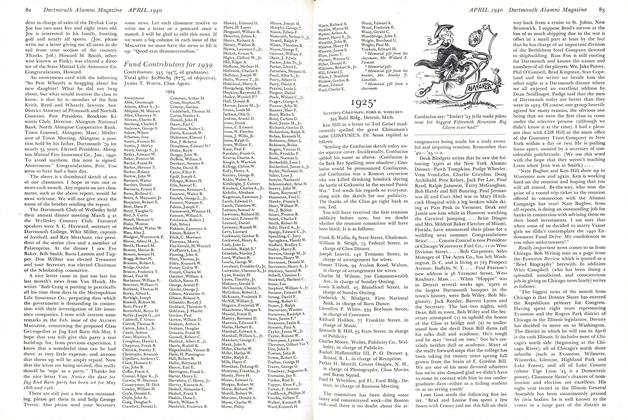

LEFT, BILL INDULGES IN HIS FAVORITE GAME OF BRIDGE WITH FRATERNITY BROTHERS. RIGHT, HE TURNS IN HIS HOCKEY EQUIPMENT TO ART THIBODEAU AT THE FIELD HOUSE, AFTER A SEASON WHICH EARNED HIM HIS FIRST LETTER.

CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 News Service director and public relationschairman for the College, who is author ofthe profile on Bill Daniels.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRich Man's College?

April 1940 By JOHN HURD JR '21 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

April 1940 By Chairman, ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

April 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1925*

April 1940 By Chairman, FORD H. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

April 1940 By Chairman, CARL F. VON PECHMANN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1923*

April 1940 By Chairman, SHERMAN BALDWIN

CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30

-

Article

ArticlePresident Reviews Social Changes

October 1936 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Article

ArticleThe D. O. C. Started Something

February 1938 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Article

ArticleThe College

NOV. 1977 By Charles E. Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

APRIL 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Books

BooksAntic Brew

April 1979 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Feature

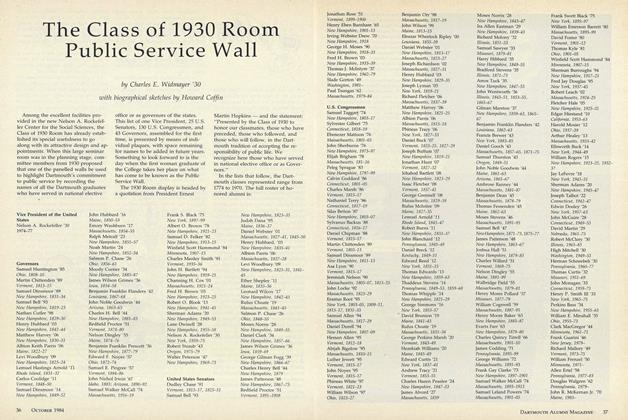

FeatureThe Class of 1930 Room Public Service Wall

OCTOBER 1984 By Charles E. Widmayer '30