[Dr. Spaulding's Autobiography of hisyears at Dartmouth (1862-66) continuedfrom last month.—ED.]

EDITED :

IN ADDITION TO MY LIKING for French, I took up Italian alone and made good progress in reading, but my pronunciation was imperfect. However, I have kept it up ever since, and nothing pleases me more nowadays than to pass the time of day and talk of the weather and of fruits in the market with the Padrone on the corner.

We once went, as a college, to Concord to celebrate some war victory, making a train of thirty cars with two engines. There was an excellent procession, and as we passed another section, I saw my brother Merrill in a crowd of boys from Portsmouth. The fire-works were glorious at night, and we came home safely after a day of great excitement.

The fall of Richmond on April 3, 1865 came to us all as a great surprise; as the event of our lives, something for which we had longed for tedious years. At times it seemed as if the War would never cease at all, particularly so to the younger men. When Richmond fell, flags came out, study was a thing out of the question, the professors let us out to our hearts' content, to cheer and run about the village and make much ado, as young chaps will. There was a great procession of students with big E. E. Hale at the head of the Seniors, and we marched to Prof. Hubbard's first, who made what we expected from him, a neat speech, for he was a neat looking man. But when Patterson began to speak, everybody knew that something pathetic was coming, and so it proved, a great oration. He was an able man, went into politics, was a Senator, but apparently became involved in the "Credit Mobilier" and the Union Pacific, and his star set in clouds of trouble and sorrow. Patterson was a handsome man, and if I remember right, he ill deserved so sad an end to his political and actual life. At all events his speech on the fall of Richmond was something great.

From there we went to Asa D. Smith, the President, who added to the eloquence of the day, glorying in the 130 men of Dartmouth who had gone to the War, first and last. He was also happy that Gen. Duncan, one of the Dartmouth boys, had been one of the first to enter the Capital of Secessionism. The speech was one of beauty of diction, as they say, and of power in argument, that for the future prosperity coming at this time young men of Dartmouth should get ready.

Finally we moved along to old Ex-president Lord, a rabid pro-slavery man, and after many calls at last he appeared, but he could not rejoice in a victory contrary to his Bible's blessing and necessity, and he spoke much against the course of the Government. We all listened with respect to the ancient man, but when he had closed his words and his door, the air rang out with cheers for Grant, Sherman, Sheridan and the Administration, not forgetting Lincoln, who unknown to us was so soon to die. This was the only rebuke that could be given to Nathan Lord.

Perhaps before I finish with Dartmouth, I ought to say that I was nicknamed "Spoddles" from the start, and have been known to all the class by that name ever since. Sometimes it has been abbreviated to "Spot" or "Spotty," but even now, when I am past eighty, I sign my name "Your devoted Spoddles," when I write to the boys.

Well, here we are at Commencement! We each had to pay a tax of ten dollars; I wonder what they pay nowadays? I fixed up my bills, something like this: "Please send me a hundred and thirty dollars for graduating and getting out of Hanover, and putting in eight dollars extra for going around by Boston." I spent considerable money, one way and another, on needless books and things to read, but I was at Hanover four years, and it cost me about two thousand dollars, every cent included; and now they tell me that the boys spend that amount in a single year.

We had a college Commencement concert with a flute solo by Otis, songs by a soprano, tenor and contralto, and three by a high soprano; then a poem was read, and people certainly got their money's worth, although I forgot to mention a pianoforte solo and a trio for three instruments. It was a good concert, even if they did not invite me to play, although I could play then as well as any of them. Our Class Day also went off very well, with a poem by Otis and an ode by Kelley, and various orations by the leading students of '66.

Commencement was a beautiful June day and a large crowd had assembled, chiefly to see Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, who was present to attend the graduation of his nephew, Henry. President Smith wore his Oxford cap and gown for the first time. Gen. Sherman was received with storms of applause, and made a stirring speech. The Civil War, he said, had been fought long enough for any one who went through it, history had taken charge of it, and that was that. A prayer was offered by Rev. Dr. McCosh of Queensborough, Ireland, and then we marched to the Tavern. Salmon P. Chase, the Secretary of the Treasury, was there as a war hero with Sherman, and somebody made a loud joke, heard by everybody, that as there was a little salmon and a few peas for those who chased them, the dinner might well be called the Salmon P. Chase.

It was also suggested that a good many people living around about always ate their dinners at home before going to an Alumni dinner, and then had a supper afterwards! Gov. Smith of New Hampshire said he would rather hear about things modern than ancient. "What did he care about Charles VIII," and when they all laughed and shouted, "Henry, not Charles," he good-naturedly retorted, "Well, Henry, if you must have him." Gen. Sherman made another excellent speech at the dinner to this effect: he was very fond of peace, but could not understand how he was having any, after being held up for a speech in the church and also at the Alumni dinner afterwardsl Altogether we had a "bully Rooseveltian" affair at our Commencement of 1866 with Pres. Smith so handsomely adorned, Gen. Sherman in the best of spirits, and the distinguished Salmon Portland Chase as a rotund speechmaker and orator.

Before really finishing with my college education, some people may say, that if I really wanted to study languages, all that I had to do was to take elective courses. This sounds well enough seventy years later, but would not have been of any use in our days, for the new president, Asa Dodge Smith, said, when asked for electives in the college, "Ah! young man, we do not give restaurant courses at Dartmouth."

Now, really to finish with my reminiscences of Dartmouth, I will say that it does not happen to many college boys to meet twenty-five years after they leave college, to say nothing of fifty and sixty years later, as happened to some of us in the class of 1866. Twenty-five years later we met at the Hanover Inn, most of us accompanied by our wives; and after an excellent dinner, each one sat or stood at his chair and told the boys what he had been doing. My theme was that if it hadn't been for Thomas Carlyle soon after leaving college, I doubt very much if I should have gotten on quite so well in the esteem of Portland people. It was Carlyle who set me to work, "at the next thing close at hand," and in so doing I always found something ready at hand day after day.

We had our "fiftieth" in 1916; Sallie and I motored over and back, having a fine tour in good weather. In Concord we found a rare pamphlet about the famous Parker murder of long ago and an account of the trial and discharge of the accused.

From Concord we reached Newport safely and lay, as I wired to the Hanover Inn, "stranded" at night; but they found us "strangled" in the message! Hanover reached, we camped out in a college building and had our meals at Commons for four days. Mrs. Lane, Mrs. Wing, Mrs. Sellew and Sallie were our class girls, and we had great times. We motored to Woodstock on three successive days and met the Chapmans and Jim Chapman's wife, whom he had married most unexpectedly to us, for we thought him a bachelor for life. Besides these drives, our car was around the village night and day for whoever wished to go anywhere; and in this way Sallie and I were host and hostess to the rest. We had a class dinner in Commons; trout fresh from a Woodstock brook that morning were served in Chapman's inimitable fashion, and after dinner the Secretary read the lives of all of us; and it was voted that I had done as much as any of them, for public health and the study of languages. The highest rank was attained by Ide, our Minister to Spain.

After the dinner we motored to Cornish and Claremont, and saw old friends and Trinity Church. Yes, and I handed around at the dinner some noble cigars worth a dollar apiece, a gift from my old friend, Machado, of Havana, and Johnson gave us $5000 to go to the college as a gift from the class.

Coming back we saw a ball game between Amherst and Dartmouth with good fielding on both sides; but Amherst won. Later on, Sallie and I motored to Etna, hoping to find the marriage lines of Ether Shepley, Sallie's grandfather, and Anne Foster of Hanover; but in vain. We called on Prof. Lord and enjoyed much talk on college history, which he had at his finger tips.

On Commencement Day we ended the procession to Webster Hall, and then the College boys separated into two lines, and we marched through them to our seats on the platform. Six boys delivered their speeches, and degrees were conferred. Then we went to the Alumni lunch, which was perfect except that, sad to relate, Wing of our Class of '66 was not called on for his Fiftieth Anniversary speech. The toastmaster just forgot him! Poor Wing should have stood on the table and said: Excuse me, but the Class of '66 has asked me to say a few words on this occasion." But he failed; it was a pity! When I askecU him for a copy to print, he had thrown it away. Just imagine anybody carrying a fiftieth anniversary speech around in his brain for that length of time, after his election to the post, and then—never speaking it!

Sallie and I left the boys at Hanover and motored to Bath up the river, and looked at the monument to "Gookin" of 1866, called on Mrs. Richardson at the Forge on Sugar liill, and then to Bretton Woods, where we met the Ether Shepleys, and found the hotel expensive. At a railroad station nearby we parted from Bishop and Mrs. Sellew, never to see them again. We motored on to Augusta, where we saw old books with notes by Dr. Benjamin Vaughan, then to Rockland and safely home. Five minutes later patients were on hand for advice and treatment. It was a most successful anniversary.

In 1926 the Class had an informal reunion, their Sixtieth. Two or three of us were there, and after it we motored to Manchester, where we dined nobly with our veteran banker classmate, the Hon. Parker Hunt. Seated around his hospitable table, we talked and talked and talked some more, until it was time for us to separate—four of us bound for Boston and neighboring towns, and myself back to my loneliness in Portland. Since then I keep up a correspondence with the remainder of the class. I attend every Commencement, and we are all living in expectant hope of meeting again for our Seventieth Anniversary in 1936.

(The End)

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleRich Man's College?

April 1940 By JOHN HURD JR '21 -

Article

ArticleMeet Bill Daniels—

April 1940 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1930*

April 1940 By Chairman, ALBERT I. DICKERSON -

Sports

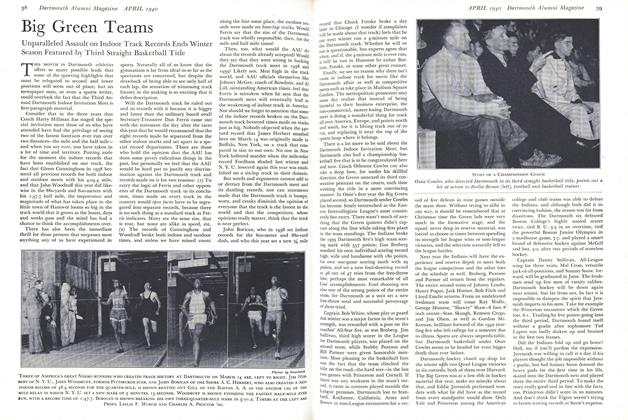

SportsBig Green Teams

April 1940 By Whitey Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1925*

April 1940 By Chairman, FORD H. WHELDEN -

Class Notes

Class Notes1938*

April 1940 By Chairman, CARL F. VON PECHMANN