President Hopkins in Final Word to Graduating Glass Asks for Intellectual Integrity, Responsibility, and Courage To Protect Ideals in Danger

(Following is the complete text of President Hopkins' Baccalaureate Address,June 16,1940.)

Ezekiel 2:1—"And he said unto me,Son of man, stand upon thy feet, andI will speak unto thee."

TODAY I WISH TO REVERSE the usual process of talking with you as undergraduates about to enter upon the wider responsibilities of a world outside of cloistered walls. Rather, I wish to talk with you as the important group within the alumni body that within a few hours you are about to become, and I wish to file a lien upon your thought and interest as to how the liberal college may more firmly establish in the undergraduate mind, which is the mind of a generation of youth unfamiliar with responsibility, a desire to know truth, the will to live in intellectual integrity, and a sense of obligation for the maintenance of courage and support of things which human experience has shown to be right. These are characteristics of a hardihood which, in Cardinal Newman's words, "we have loved long since and lost awhile."

There is no superstition among the many baseless notions of student life that is quite so much of an absurdity as the frequently reiterated stereotype in regard to the college alumnus. Needless to say, it would be preposterous if the sole result of the educational effort exerted by the college were the production of a mentality so inferior to that of the undergraduate as is frequently assumed to be the case in student discussion. Obviously, likewise, it would be a parody on the aspirations of generations past in regard to opportunities they wished to leave to posterity if in completing the college course a man classified himself as less intelligent than previously.

It is upon the attitudes and upon the accomplishments of the alumni that the reputation of the College rests. To be unemotionally realistic in regard to the matter, altogether the most important interest which the College has in the undergraduate is as to his potentiality through intelligent thinking and intelligent action to become of discriminating service to the society which has made his education possible and of which he is to become a part with responsibility for the education of others. Consequently, it is to you as the alumni of a few hours hence that I shall speak, for it is upon you in vital measure that it will devolve as trustees of a great tradition to carry Dartmouth's torch of learning and of liberty .. as they Of Greece perform in ages gone When the fleet youths, in long array, Passed the bright torch triumphant on."

I crave your consideration with me for a few moments in examination of the liberal college at points where it appears to many to be open to criticism.

There was in Biblical narrative a young priest named Ezekiel who underwent a deeply stirring emotional experience. An exile standing among his fellow captives by the River Chebar, he felt himself called to prophecy and he seemed to see the heavens open and to see visions of God. Falling upon his face in abject humility, he heard a voice that said, "Son of man, stand upon thy feet, and I will speak unto thee." In reciting his experience, he said that the spirit entered into him and set him upon his feet so that he heard what was spake unto him.

UPRIGHT MAN STANDS ON HIS FEET

It is interesting how definitely throughout literature this idea of standing connotes self-respect: "The diligent man who stands before kings"; "men who can stand before a demagogue"; "united we stand, divided we fall" and a multitude of similar phrases all are of the same significance. Furthermore, for those who are interested in semantics, consideration can be given to how frequently "arising" is a preliminary to action, as in the statement of the prodigal son, "I will arise and go to my father," or how almost exclusively integrity is deemed to attach to the upright.

In these cases, moreover, the figures of speech are indicative of fact. The hypothesis of Aristotle that man's gift of intelligence is associated with the fact that alone among animals he walks erect is vindicated under the insistent scrutiny of modern science. It is not simply that in standing up our early ancestors released their hands for other purposes than to walk upon; it is even more that in changing the level of their vision they extended their horizons to greater distances and thus became more largely comprehending of areas of life around them. It is to this aspect of spiritually and intellectually standing upon our feet and getting an all-inclusive view of life that I wish briefly to call attention.

In the great lexicon of life, owing to modern conditions, the years of childhood and of adolescence which men like yourselves have encompassed have been less an education in their effect than a preparative for education, a cultivating of receptivity towards and a discrimination among the values which life shall offer. Specifically, in the highly complicated organization of society today, that man lacks education who lacks experience. No man is qualified to utilize education helpfully to his fellow men who has not had occasion to some extent to measure his capacity for self-sacrifice or for enduring hardship. No man is qualified to be dogmatic about life until he has reckoned the extent to which he would be willing to forego self-indulgence physically or in intellectual exhibitionism for the sake of helpfulness to others than himself or to the end of creative or constructive accomplishment. The man who with brilliancy of mind and persuasiveness in the use of words undertakes without experience to dictate what shall be the circumstances of life about him may become a social menace. Plato, in his familiar passage so frequently quoted, states the principle:

"Until philosophers are kings, or the kings and princes of this world have the spirit and power of philosophy, and political greatness and wisdom meet in one, and those commoner natures who pursue either to the exclusion of the other are compelled to stand aside, cities will never have rest from their evils,—no, nor the human race, as I believe,—and then only will this our State have a possibility of life and behold the light of day."

In former times when conditions of life were harsher and when practically every man in college had had experience of his family in contributing from early childhood to its support, there was inevitable comprehension in regard to the essential details of life which in these times are not frequently available to youth. Thinking was not done in such an atmosphere of irresponsibility as attaches to the colleges of today and rationalizing was done with an acquaintanceship with reality which tempered its dogmatism and refined its understanding. It is the lack of checks and balances such as these and it is the inability of the college to compensate for their lack that makes the higher education of today so incomplete until supplemented by experience. Whether consciously or unconsciously, many of the spokesmen of undergraduate bodies in America today have given impression of the undergraduate as one unwilling to stand upon his feet or to listen to any voice excepting the echo of his own desires.

And perhaps the undergraduate is justified in his inquiry as to why should he. The political liberties, the material prosperity, and the lack of social strain of caste or classes in America have created a society that required little of its sons. The selfdenial of countless of their forebears, the generosity of contemporary benefactors, the prodigal appropriations of public funds, the struggle of devoted parents craving every advantage for their children,— these have been made available to any one seeking them, representing at the same time opportunities available nowhere else on earth except to beneficiaries of special privilege. Meanwhile, in some proportion, though definitely a minority, recipients of these endowments, without sense of value of blessings they have never lacked, shrink even from accepting the implications of hard conclusions, utilizing rather an acquired cleverness in bending arguments to conclusions they wish to accept. If required to answer Isaac Watts' rhetorical question, "Must I be carried to the skies on flowery beds of ease?", the tacit reply of many a man would be, "Yes."

The first meaning of culture was cultivation of the ground for the raising of crops. This required labor and sweat and earthy strength, such as Antaeus always felt when he stood with his feet upon the ground. The secondary meaning, "development of the mind," if to be sought under formal auspices, originally required the hazards and difficulties of travel over long distances, the undergoing of hardships, and the enduring of the rigors of poverty. These were the automatic offsets that tempered and controlled the vague thinking and the specious dialectics to which men otherwise were led by the processes of formal education. Today there are no such controls. Without them our colleges seem to many of us to be becoming less and less capable of performing their desirable functions as educational establishments.

No man who thinks responsibly of education can speak in such a time as this without thought of the lowering threat in the world to all that has made life worth living and has made the past high accomplishments of education possible. And never before have the inadequacies of present-day education to be helpful to all been as definitely exemplified as by many who purport to speak for the student population of institutions of higher learning in America today. There is abundant reason for regret concerning the unconscious selfdelusion of the man who escapes self-judgment for avoiding obligation by claiming major importance for some plausible and otherwise desirable objective. There is even greater reason for concern in regard to the influence of the colleges in the apprehensions amongst student groups lest some word or deed offend the protagonists of force and brutality, race extinction and mass murder. There is at least some basis for inquiry as to the extent to which the college breeds discriminating intelligence when hundreds of men sign petitions to the President protesting that they see nothing of a struggle against the forces of evil in the present exigency. There is concern about the relationship of intellectual development and common sense when undergraduates argue against a preparedness against double-dealing to which other peoples have been subjected and against which we are not defended. There is a widespread bewilderment as to how the intelligent man can so ignore precedent as to believe that anything more than a temporary immunity for us is available from the attacks of a group that has defined its antagonisms to everything which our race has sought to establish for centuries past and for which it stands today. The conclusions alike of the man on the street and of those in high position in regard to undergraduates of today are likely to be that they are a softened generation which capitulates easily to what it deems to be self-interest. The fact that these attitudes are representative of only minority opinion in undergraduate groups does not save the college from indictment. But the ultimate in attitudes amongst the undergraduate generation of this period of crisis and the factors calculated, if enduring, to be violently destructive of confidence in the college of today are the hard materialism and the cynical indifference of some few in every college group who admit that not only would they have a free people abase itself but would, if practicable, compromise with the murderous sponsors of indecency for such respite as might in return be granted to us. Neither the word of the Lord nor the understanding of man can be invoked for these until they stand upon their feet.

To repeat what I said at the opening of the college year: The time has come for us to recognize the fact that for seven hundred years the Anglo-Saxon race—l use that blanket term—has been striving to achieve a form of government, an organization of society, and a manner of living which on the one hand should give order to life and on the other hand should give freedom and liberty in the maximum degree to the individual. And the time has come for us to recognize that in our country and among the people whom we know those ideals have been more fully achieved than they have been anywhere else in the world. It has been the vogue for the past two or three decades to emphasize the weaknesses of mankind. If there were any idols among mankind, we have looked for the clay at their feet rather than for the gold above; if we have discussed public men, we have discussed their weaknesses rather than their strength; if among peoples there have been mixed motives of idealism and materialism, we have dwelt wholly on the materialism. For some obscure reason, in our collegiate bodies and among our intellectuals it has become presumably a sign of intelligence to be pessimistic and to be cynical—all of which seems to me to be contrary to the spirit of which the college should be representative and contrary to the spirit that will make this eventually a better and a sweeter world.

Finally, Men of 1940, there is the personal word which I wish to say to you quite apart from any comment incident to a formal address. There is among us who remain in the College always a sense of impending loss at a time like this. It is difficult to think of the College without your presence, your participation in its affairs, your companionship. Yet, in the large, Dartmouth rejoices that it is to be given this added representation in the world's affairs. It rejoices in the qualities which it believes to be yours as you go forth as its plenipotentiaries. It has faith in your greater importance to society as citizens even than to the College as undergraduates,—and this has been very great. Oliver Wendell Holmes speaks of hearts with inscriptions on them which like that on Dighton Rock are never to be seen except at dead low tide. Yours we have sometimes seen and we know the qualities which they fundamentally bespeak—aspiration, steadfastness, and uprightness. And God for whose glory this college was founded is as eager to have you as His spokesmen as ever He was to have Ezekiel, and He awaits the moment when with receptive ear you will listen to Him as he promises, "Son of man, stand upon thy feet and I will speak unto thee."

BACCALAUREATE AUDIENCE OVERFLOWS ON LAWN, HEARS ADDRESS OUTDOORS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleCommencement Climax of 171st Year

July 1940 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThirtymen Celebrate With Record 265 Reuners

July 1940 By BUD FRENCH '30 -

Class Notes

Class NotesThirtieth Reunion of 1910

July 1940 By H. P. HINMAN -

Class Notes

Class NotesGreat Twenty-Fifth for 1915

July 1940 By DONALD C. BENNINK -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Remembers' Craven

July 1940 -

Class Notes

Class NotesFifth Reunion of Class of 1935

July 1940 By THE SURVIVORS

Article

-

Article

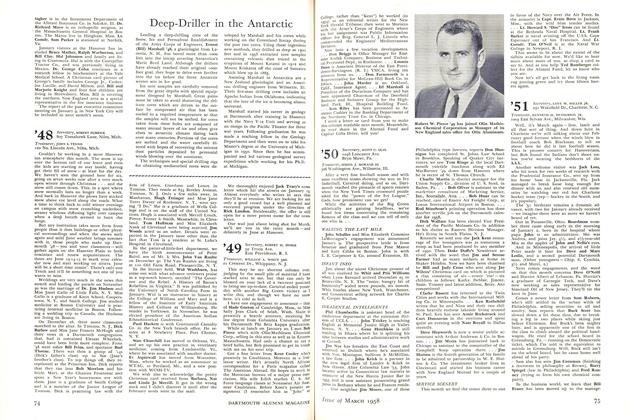

ArticleDeep-Driller in the Antarctic

March 1958 -

Article

ArticleStorage for Dying Languages

December 1995 -

Article

ArticleFINANCES

DECEMBER 1962 By C.E.W. -

Article

Article"More than Teacher"

JUNE • 1986 By Dorothy L. Foley '86 -

Article

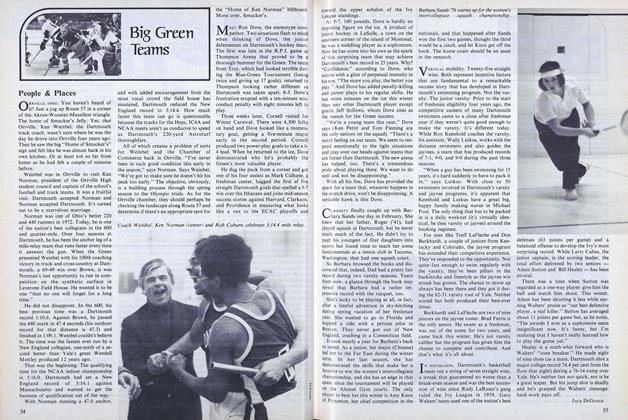

ArticlePeople & Places

March 1976 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

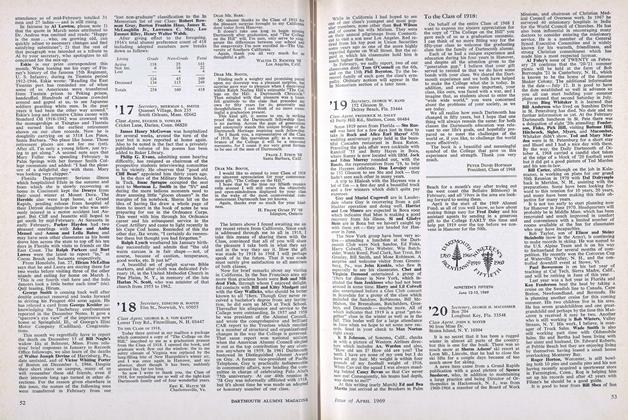

ArticleTo the Class of 1918:

APRIL 1969 By PETER DAVID HOFMAN