The Background, Trials, and Tribulations of Camp William James Predicted a Beginning Toward Realities

[In this Undergraduate Issue of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE the editors include the accompanying descriptionof the beginnings and frustrationsthat have marked the course in recent months of interest among Harvard and Dartmouth alumni andundergraduates in a work-servicecamp. The neighboring villages ofTunbridge and Sharon, Vt., havebeen and still are the locale of themovement which has spread, in itsinterest, to all parts of the country.Mr. Kuhn, author of the review ofWilliam James Camp, is a junior andan editor of The Dartmouth.—ED.]

IN VERY CONCRETE, material terms, Camp William James six weeks ago consisted of a group of 26 young men—13 of them college men, 13 of them CCC men and recruits from farms around Tunbridge, Vermont—living in a small ram- shackle farmhouse about two miles outside of North Tunbridge, cutting fifty cords of wood on contract, working for their meals and what cash wages the farmers could pay them, and living together, cooking together, working together, making them- selves a part of the community whose work they were helping to do.

But those concrete terms only give a beginning of the story and only a beginning of what the members of the Tunbridge Movement—or Camp William James or whatever name is applied—hope to do. That small, unified, harassed group represents the beginning of an idea at work—an idea to bring together boys from colleges, from farms, from city streets in a working group such as the CCC never realized. The working group, living together in close terms, sharing a life of work for a time, is part of the ideal of Camp William James. Another part of the ideal is the accomplishment of specific needed tasks on the land and in the community in which they live.

That concrete beginning is an endproduct in a way though, because it represents a very critical point in the history of the work-service ideal as it has materialized for Dartmouth men. And the history itself is one in which a starting-point is hard to find.

Part of the start of the Tunbridge Movement comes from an essay by William James, "A Moral Equivalent for War," in which that American philosopher early in this century advocated work service for youth as a means of building national fibre and providing an adventurous and creative medium for the energies of the nation's young men. The 26 men at the farmhouse have named themselves Camp William James in acknowledgement of their debt to him for their ideal.

Another thread in the history is the work of Professor Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, whose classes in Social Philosophy at Dartmouth have been called the most provocative and valuable in the College by a number of men, including some of the Dartmouth men now at Camp William James. Prof. Rosenstock-Huessy, early in the century, worked in Germany for the achievement of the work-service camp and for its establishment and spread throughout post-war and pre-Hitler Germany. At Dartmouth last year, Prof. Rosenstock Huessy and his classes, seeing the CCC as one very incomplete and in many ways unsuccessful manifestation of the workservice idea, went to what was then a "side-camp" of about fifty CCC boys at work in the Downer State Forest neat Sharon, Vermont. He began to build between the students and the CCC boys a friendship and a reciprocal relationship that made itself felt in joint competitive athletic activities—in basketball games in the Alumni Gym, in wrestling and boxing matches—and also in bull-sessions, and joking and the beginnings of a real understanding and friendship between many of the boys. That interest in the CCC camps in general, and in the camp and community at Sharon in particular, is one thread of major importance in the history of Camp William James.

But the main thread of concrete accomplishment finds itself in a number of separate fibres—six fibres to be exact. Those fibres were the six Dartmouth men—five of them recent graduates and one of them an undergraduate—who last summer, of their own volition, separately, and with totally different aims but largely the same inspiration, went to Tunbridge to offer their services on farms. They worked, and worked hard, for their meals and a place to sleep, and for what spending money the farmers they worked for and lived with wanted to give them. One of the six was interested in regional planning, and wanted close-hand experience in the problems of the White River Valley area. Others were working for practical experience in farming and settlement problems for theses, or just for the experience of spending a summer at hard manual labor.

To MEET A NEED

What grew from the work of these six men—Art Root '40, A1 Eiseman '40, Jack Preiss '40, Bob O'Brien '4O, Bud Schlivek '40, and Bill Uptegrove '42—was an understanding of the great needs of the Tunbridge community and of similar communities throughout Vermont and New Hampshire—needs that could be answered by work-service of young men—needs that were not being answered by the CCC. The CCC had failed to work in conjunction with the communities, had failed to answer their specific local problems, and was unable to carry on much-needed work on private property because of the laws under which the federal camps operated.

And so the understanding of the needs and the feeling for the community and for the value of their work combined with such outside support as Dorothy Thompson, who, a neighbor to the Tunbridge community, became interested in the work of the six Dartmouth men during their summer in Vermont, and Frank Davidson, a Harvard graduate who had made a study of the work-service ideal and of the CCC camps. The combination of the six Dartmouth men, the outside supporters, and the farmers and townspeople of Tunbridge came on September 25, 1940, in the Town Hall in Tunbridge, where Dorothy Thompson spoke, where some of the Dartmouth men spoke, where Nathan Dodge of Tunbridge, an ardent supporter of the boys, spoke. From the meeting of September 25 came a petition to the President of the United States to open, under federal auspices, an experimental camp on the site of the Sharon CCC Camp, which had been removed in the spring. By January first the experimental camp had federal approval; the camp, set up under the Department of Agriculture, was to work in conjunction with the community in the achievement by hard work of needed tasks in rehabilitating deserted or rundown farms, in the fighting of soil erosion, in reforestation, in small stream-control projects, in road-repair.

January l, 1941, saw what looked like a real start for a real experiment. The six Dartmouth men, one of whom dropped out to return to college, were joined by other Dartmouth graduates interested in the work and by Harvard graduates, and by a large number of CCC recruits and local farm and town boys interested in the work of rebuilding a community. There were forty-five men—young men, from all parts of the country, from all environments—who went to work after January first in building their own barracks at the Sharon Camp site. By February 1 their barracks were well on the way to completion. And by February 1 opposition to the camp began to take form in Washington.

Opposition, enough of it to cause the rescindment of the original approval of the experimental camp, came in the form of a blast on the floor of Congress by Representative Engel of Michigan who condemned the group as a "camp for the overprivileged." J. J. McEntee, director of the CCC in Washington, because of the opposition, or because of fear of the success of the camp and subsequent investigation of the success of the CCC (the explanation the Tunbridge group chooses to give), placed the camp under the regular CCC again, took away its experimental status, and made it impossible for the group to accomplish its projects designed for work with the members of the community on private property. CCC camps may not work on private property; placing the camp under the three C's again meant making it the same as the Sharon camp had been before. The members of Camp William James as well as the backers of the camp from Tunbridge and surrounding townships were convinced that the work of the previous camp under the CCC had been of no value in solving community problems. They were convinced that Camp William James, if it were to be of any aid to the community, must be free to work on private property, must be free to work in conjunction with the local farmers in planning work projects—in short, that the camp must be free from the corps.

There came the turning point to the history of Camp William James. The college men associated with the camp promptly resigned from the CCC; just as prompt were the resignations of some 15 of the CCC boys who had joined them at the Sharon camp site. The remainder of the CCC enrollees, because their families needed the security of a certain job, were taken into other CCC camps, or else left to start work as apprentices in machine tool plants in Springfield, Vt„ and Springfield, Mass. The Sharon Camp was again shut down. The members of Camp William James found private support after much effort. The town of Tunbridge found a farm house, the farm house in which the Camp is now located, which the boys have used for living quarters in return for their labor in cutting wood and splitting firewood. $1000 was donated by Mr. and Mrs. Henry C. Greene of Cambridge, Mass., for the purchase of a suitable camp site for the group. Various other private donations have helped supply the wherewithal of existence for Camp William James.

But what is most important in the development of the past three months, since the abandonment of the Sharon Camp, is the fact that Camp William James has had to be an almost entirely self-supporting proposition, fighting against the tremendous odds of the draft and the appealing jobs open to the CCC men and the local farm and town men in defense industry. The private funds have been little touched; Camp William James in one week in March cut twelve cords of wood and delivered eight of them. With the coming of the sugaring season in Vermont, they went to work with the farmers. For their labor they accept payment in food and in whatever cash their employers can pay, usually amounting to less than $3 a day. Wages earned by the members are their property if the wages are needed to be sent home for the support of their families. In every case, where a family of one of the members needs the money, $22 a month is sent to the family, and $2 a week is kept by each member of the camp for spending money. All other money is put into the Camp's treasury, which supplies the funds for buying food.

That means, coming back to the concrete, material beginnings that Camp William James represented some weeks ago when Bill Cunningham came to Tunbridge to learn the story of the camp, that Camp William James is having to earn its own way, fight out its own problems of keeping together while members of the camp are being drafted, and accomplish its purposes of doing useful work for the community in which it exists. There it is a beginning, and there it is faced by problems that make any realization of its aims at doing any work of major importance to Tunbridge look rather slim, at least in terms of the near future. Page Smith, Dartmouth '40, who joined the camp in January at Sharon, and who became one of its leaders, was drafted in early April. Page Smith was Camp Manager, elected by a vote of all members.

The draft is a problem alongside that of keeping up the personnel in spite of the economic temptation for some of the poorer members of the camp to seek jobs in defense industries. And the problem of support for the camp is still large. Maintaining the camp as a self-sufficient unit for a long time is not feasible; the members of the group and the supporters in Tunbridge realize that outside support, whether public or private, is needed for the continued existence of the camp.

In Tunbridge and in the surrounding towns of Sharon, Royalton, South Royalton, North Tunbridge, and others, the need for the work of the Camp is stressed. Mr. Flint, the owner of the Creamery in Tunbridge who has two sons working in Camp William James, spoke in March to Bill Cunningham about the need for the labor of the young men. He told of how the draft and jobs in defense industries had drained the towns of their native farm labor. From his story of the need for labor on farms and in the communities can be drawn, without going beyond the examples of the effect of the last war on rural New England, the correlaries of more run-down and deserted farms, more depopulated communities, and the growth of the number of communities with high average ages. The need for the labor is emphasized at every turn; the need for support for the camp is emphasized by the members who are struggling to keep together in a group, who are working hard to keep themselves in food, and who are working hard, in small but much-needed jobs, to try to realize their goals of achieving useful work for the community in which they live.

Bill Cunningham called the members of Camp William James "youthful idealists," and such they must remain as long as their efforts to achieve their high goals are beaten down by the realities of national defense and the draft. But Camp William James still, and always, considers itself a beginning. As a beginning it is fighting hard to make its ideals into realities.

PROF. EARL R. SIKES (LEFT), HANOVER HOLIDAY SPEAKER "Economic Efficiency in a Democracy" will be his subject in the week's series of facultylectures and alumni discussions in Hanover, June 16-20.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ORTON H. HICKS -

Article

ArticleWhat of the Senior Fellows?

May 1941 By THEODORE WACHS JR. '41 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1941 By CHARLES BOLTE '41 -

Article

ArticleCourse Elections Stressed

May 1941 -

Article

ArticleOdyssey of Songsters

May 1941 By James H. Rendall Jr '42 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1911

May 1941 By PROF. NATHANIEL G. BURLEIGH, JOHN C. STERLING

CRAIG KUHN '42

-

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

June 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

October 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleINDIVIDUALS WEAKEN THE WHOLE

November 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleJUST A MATTER OF FRAILTY

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleSIGNS OF AWAKENING

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42

Article

-

Article

ArticleWISCONSIN ALUMNI ASSOCIATION MEETS MONTHLY

April, 1923 -

Article

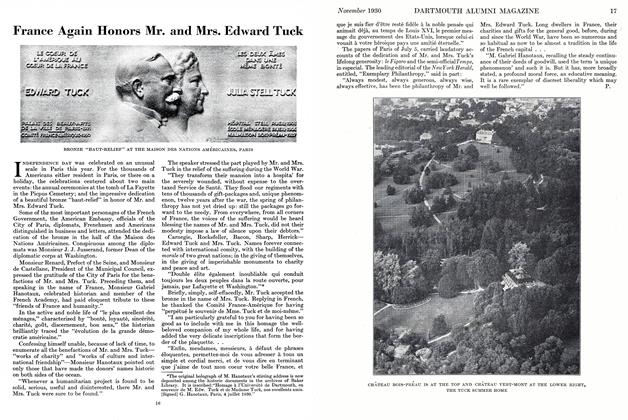

ArticleFrance Again Honors Mr. and Mrs. Edward Tuck

November, 1930 -

Article

ArticleSUGGESTIONS

October 1937 -

Article

ArticleDTSS, Inc.

NOVEMBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleChasing the Best Burger

September | October 2013 By Lauren Vespoli ’13 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER STRAW-VOTES

February 1936 By W.J. Minsch Jr. '36