Green Key Week End Expresses Spirit of Undergraduate College as Abundant Spring Slips Swiftly By

By the middle of May all the trees were fully leaved and the lilacs were in bloom along Mass Row and the quiet streets where professors live. This has been a smooth-flowing, fast-maturing Spring. From the end of Spring vacation early in April it has been a swift, intensely budding season of sunny, warm days and cool nights. It has seemed that the season, too, has been under some kind of pressure to achieve full blossom before an unset deadline, somehow sensing that its existence and flowering are too good to be allowed an immature death.

This is parallel to the pressure under which the undergraduate body has lived, desiring the fullness of Spring and the physical, growing joy that has made classroom routine and note-taking seem artificial. None of the pressure has been expressed in words. To say it's only the imminence of war and the uncertainty of the future is to leave out the fact that this Spring in Hanover, of all Springs, has been the fullest and sweetest and has most grown into the College. The Spring and the war have worked together to make the Dartmouth of 1941 a place where the academic life has reached its lowest ebb of importance.

This doesn't mean that the students, any of us, have given up to Epicurus and the gods of the "Lost Generation." If that were the case, there wouldn't be the healthy life of thinking and strong physical enjoyment. There wouldn't have been the excellent mass bull-session in 105 Dartmouth the night that Charles Bolt 6 '4l and David Loughlin '43 argued that "America should go to war with Germany" against Clifton Stratton '4l and George Brand '4l. If Dartmouth now were a place of shattered hope and prodigal, irrational wildness, that debate wouldn't have drawn the goo students "who stayed for three hours to make one of the finest bull-sessions ever known on the campus.

Charles Bolte's "Letter to the President," reprinted in this section from TheDartmouth of April 24, was the percussioncap for the explosion of discussion and Feeling that led up to the war debate, that crowded the Vox Populi columns of the paper, and that made dinner tables and dormitory rooms centers of argument on the war. Bolte's letter in no way represented majority campus opinion, the campus learned, because its force was stronger than campus lethargy. The letter aroused the campus, split the thick silence on the war, and brought into activity the desire of the College io find itself in relation to the war in which America is involved.

The Bolt£-Stratton debate came shortly after the letter. At 8:30 on the night of April 29, 105 Dartmouth was crowded with more students than attended any lecture all year. The debate was to be a "no-decision" discussion. Bolte and Loughlin, who earlier in the year wrote in The Dartmouth an article called "One Man and the War," in which he said "It's a lousy fighting chance, but I'll take it," supported with faith and facts the assertion "We want to go to war now because it's the best way to save America." Stratton and Brand (President of the Forensic Union) supported non-intervention and the contention that "a nation can't take a 'lousy fighting chance'—it must be selfish and take care of its own people." They argued with facts and with debater's logic. The formal argument of the debaters and the informal argument of Bolt 6 and Loughlin lasted for about one hour. There was no decision of the kind that is given after a debate.

More heartening than the unquestionable sincerity of the debate itself, and more important to the campus, was the long, agonizing, patiently searching freefor-all bull-session that brought questions from the floor, that brought hesitant, honestly-considered answers from the debaters, and that made students of all classes mount the platform to speak their beliefs. If nothing else was decided at the meeting, it became certain that there could be no unified decision of the College in regard to the war. The decisions made that night were the individual decisions of students finding their place in relation to a nation at war. Words like "idealism" and "democracy" and "selfish nationalism" were used often; they were seldom used glibly, and they were never adequate.

One freshman, who for three minutes edged his way gingerly up the steps of the platform, finally won the rostrum after cheers and laughter. He stood for two minutes, talking quickly, asking questions with great intensity. "How can we maintain ourselves in isolation.... in a contracting democracy .... from the rest of the world? ... .We are living in a new age. . . .the nations of the world must depend upon each other....no nation can remain self-suffi- cient or isolated. I don't think we can. .. . America cannot isolate herself in a contracting democracy," he said, talking fast and self-consciously. He was applauded when he left the platform.

The meeting lasted until 11:30. The entire conduct of the discussion and question-and-answer period was one of calm determination to understand and to make understood the place of a lot of college men and a war that is shaking their lives and wringing their futures. The students who left the meeting that night were no more certain of the future than when they entered, but they were aware of its uncertainty and of its demands in decision and action.

Campus concern with the war was drawn into focus by the debate; since then the student body has shown a great preoccupation with the war, a continuing distinterest in organized learning, and a growing desire for strengthening the organic relations of friendship and group work and play. The pressure of uncertainty, each day more intense, has shifted the emphases of life on the campus and has shown in strong relief the inadequacies of the present College framework to cope with the realities of a war that must involve all its members.

One attempt to make the College adequate to the demands of a nation at war was the curricular analysis made under the sponsorship of the American Defense Dartmouth Group, the various educational departments, and The Dartmouth. The date for filing electives was extended one week; The Dartmouth published a series of feature articles and interviews on the relation of various existing courses in the College to work in defense industry or in the military services. For the most part, the analysis showed little that wasn't already knownthat the education given in a liberal college won't teach a man about machinery in a defense industry, or to plot the trajectory of a shell, or to navigate a ship or an airplane, unless the student specifically seeks courses concerned with those jobs. The scarcity of courses of a "practical" nature was not surprising; the correlation of requirements for military training with courses offered was of value to students planning for specific service in national defense. The defense survey didn't attempt an answer to the question: "How can a general liberal arts education help a man drive a tank?" That question was just another form of the same problem that has, with daily-increasing rapidity and strength, been coming up squarely before the individual student and forcing him to make his own answers.

HANOVER HOLIDAY SPEAKER Prof. Dayton D. McKean of the PublicSpeaking Department, author of a bookabout Mayor Hague of Jersey City, willdiscuss "Democracy in Practice" in one ofthe lectures of the alumni college, June 16to 20.

EDITOR'S NOTE: With this issue JamesCraighead Kuhn Jr. '42 of Pittsburgh, Pa.,assumes occupancy of The UndergraduateChair. He is fourteenth in the line ofgifted Chair occupants and succeedsCharles G. Bolte '4l, whose catalytic letterto President Roosevelt is described in thissection. Kuhn is Editorial Assistant of The Dartmouth and is an honors student inphilosophy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleThe Dartmouth College Eye Institute

June 1941 By C. E. Widmayer '30 -

Article

ArticleA Versatile Engineer

June 1941 By Edwin A. Bayley '85, William P. Kimball '28 -

Sports

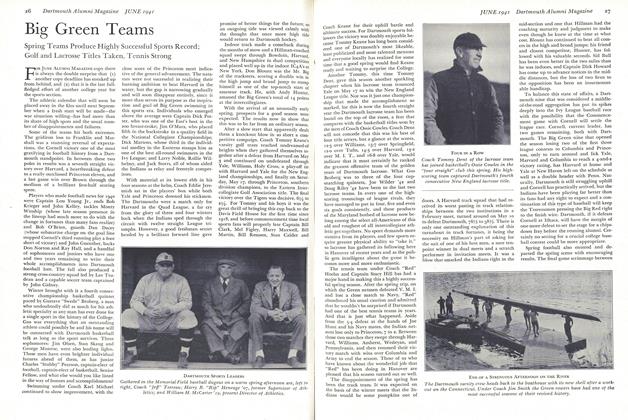

SportsBig Green Teams

June 1941 By Whitley Fuller '37 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921*

June 1941 By CHARLES A. STICKNEY JR., ORTON H. HICKS -

Class Notes

Class Notes1929*

June 1941 By F. WILLIAM ANDRES, VAN NESS JAMIESON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1917*

June 1941 By EUGENE D. TOWLER, ARTHUR P. MACINTYRE

Craig Kuhn '42

-

Article

ArticleIdeals of Work-Service in Vermont

May 1941 By CRAIG KUHN '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

October 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

November 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleJUST A MATTER OF FRAILTY

December 1941 By Craig Kuhn '42 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1942 By Craig Kuhn '42