Original Steel Die, in Use 168 Years, Is Verified as Authentic After Study of Seal's Many Variations

THE DARTMOUTH COLLEGE SEAL came to light in 1773, when it was adopted at a meeting of the trustees the twenty-fifth of August. On that occasion—the last meeting attended by Governor Wentworth, by the way —the Honorable George Jaffrey presented a steel die mounted in an old-fashioned screw press, and his fellow trustees found it good. The following description was entered in the minutes of that day's business:

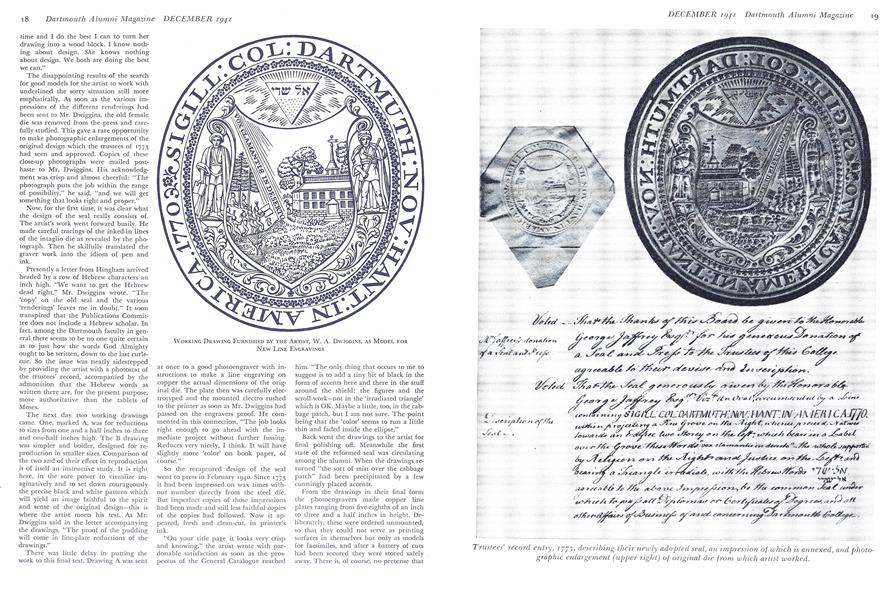

An Oval, circumscribed by a Line containing SIGILL: COL: DARTMUTH: NOV: HANT: IN AMERICA, 1770. Within projecting a Pine Grove on the Right, whence proceed Natives towards an Edifice two Storey on the left, which bears in a Label over the Grove these words "vox clamantis in deserto"—the whole supported by Religion on the Right and Justice on the Left, and bearing a Triangle irradiate, with the Hebrew words [EI Shaddai].

An impression of the seal was thoughtfully appended to this description in the trustees' records. But for this thoroughness on the part of the clerk we might still be wondering whether the female die now in the treasurer's office were really the original one. The written description is ambiguous in its use of right and left: When the keeper of the records placed the pine grove on the right he must have been looking at the die itself, and then at an imprint from it when he located the figures. In any case he has certainly transposed these elements, but no harm is done for there is the impression of the seal clearly establishing that our present die and that of 1773 are identical.

During 167 years the old steel die has been in constant service, except for the brief period when the College was a university and its seal was sequestered in Mrs. Woodward's feed bin. Still in good condition, it remains, as the trustees' record says, "the common Seal under which to pass all Diplomas or Certificates of Degrees, and all other Affairs of Business of and concerning Dartmouth College."

No clue seems to have survived regarding the designer of the seal or the source of his inspiration. The record only asserts that the female die was engraved in accordance with the trustees' "devise and Inscription," which suggests that several hands may have had a part in it. And save for the authoritative word of Frederick Chase we should not even know that the engraver was Nathaniel Hurd of Boston, a preeminent early American craftsman. Hurd's brother, Colonel John of Haverhill, was among the gentlemen who were awarded the honorary degree of master of arts on the same day the seal was adopted, but that apparently has nothing to do with the case.

For the first hundred years and more the die was used only for impressions on wax. In 1876 it was fitted with a corresponding male die and since then blind impressions have been stamped directly on to the writing surface of diplomas and other documents calling for this imprimatur.

Meanwhile, apparently about the time of the Dartmouth centennial celebration in 1869, the problem of converting the sculptured design into linear form, suitable for reproduction with letterpress, raised its ugly head. The first effort of the sort that I have observed appeared on the title page of The Dartmouth for January 1869. It is in the wood-engraving tradition of the time, and the artist, either through misunderstanding or with the deliberate intention of improving on his model, drew quite away from the design on the die. It is perhaps significant of the high Victorian epoch that this artist saw the foreground figure within the shield not as a late savage turned husbandman but as a frockcoated gentleman standing on the front lawn and observing seven Indians in the distance.

Another line drawing, this time published in Chase's History (1891) emphasizes the hazard, even to a scrupulous antiquary, in attempting to turn such modeling into flat black and white. But bad as it is the Chase version of the seal is hardly improved upon by subsequent efforts. During successive stages of degradation the native delegation was decimated, the grove deforested, the edifice remodeled, the garden untended went badly to grass, religion and justice were debauched and even the crying voice was rendered vox clamatis in the official printing of the College charter.

This was the situation when the time came last year to prepare the new General Catalogue, a fifteenyear event which the Publications Committee thought certainly ought to have a decent reproduction of the seal. A thorough canvass of all the available line engravings revealed even to uncritical eyes that no such thing existed. The predicament was reported to President Hopkins and he immediately authorized a fresh start to recapture the spirit and significance of the design on the original die of 1773 so that it could be printed in the new catalogue.

For this task, at once delicate and formidable, the Publications Committee were fortunate in securing the help of W. A. Dwiggins. Mr. Dwiggins is a distinguished calligrapher, type designer, author, typographer and illustrator. Moreover he is an experienced hand with emblems, marks, seals and coats of arms, and before now had brightened the tawdry escutcheon of more than one great institution of higher education that had fallen into similar difficulties. After an exigent appeal by telephone, since the case was so urgent, the Publications Committee made a bundle of the Chase History, some blind pulls from the die in the treasurer's office, and all the proofs from linecuts that lay ready to hand, and despatched the lot to Mr. Dwiggins.

The artist's response was prompt but it was not encouraging. "In this case," he said, "you have a desperately bad design to start with—as design. Made by the niece of the bursar of the day, no doubt, and cut by an engraver who couldn't possibly turn the niece's drawing into relief The best formula to act on would probably be: Assume the niece's drawing in hand, a delicate water-color drawing. Assume that I am a wood-engraver of the time and I do the best I can to turn her drawing into a wood block. I know nothing about design. She knows nothing about design. We both are doing the best we can."

The disappointing results of the search for good models for the artist to work with underlined the sorry situation still more emphatically. As soon as the various impressions of the different renderings had been sent to Mr. Dwiggins, the old female die was removed from the press and carefully studied. This gave a rare opportunity to make photographic enlargements of the original design which the trustees of 1773 had seen and approved. Copies of these close-up photographs were mailed posthaste to Mr. Dwiggins. His acknowledgment was crisp and almost cheerful: "The photograph puts the job within the range of possibility," he said, "and we will get something that looks right and proper."

Now, for the first time, it was clear what the design of the seal really consists of. The artist's work went forward busily. He made careful tracings of the inked-in lines of the intaglio die as revealed by the photograph. Then he skilfully translated the graver work into the idiom of pen and ink.

Presently a letter from Hingham arrived headed by a row of Hebrew characters an inch high. "We want to get the Hebrew dead right," Mr. Dwiggins wrote. "The 'copy' on the old seal and the various 'renderings' leaves me in doubt." It soon transpired that the Publications Committee does not include a Hebrew scholar. In fact, among the Dartmouth faculty in general there seems to be no one quite certain as to just how the words God Almighty ought to be written, down to the last curiecue. So the issue was neatly sidestepped by providing the artist with a photostat of the trustees' record, accompanied by the admonition that the Hebrew words as written there are, for the present purpose, more authoritative than the tablets of Moses.

The next day two working drawings came. One, marked A, was for reductions to sizes from one and a half inches to three and one-half inches high. The B drawing was simpler and bolder, designed for reproduction in smaller sizes. Comparison of the two and of their effect in reproduction is of itself an instructive study. It is right here, in the sure power to visualize imaginatively and to set down courageously the precise black and white pattern which will yield an image faithful to the spirit and sense of the original design—this is where the artist meets his test. As Mr. Dwiggins said in the letter accompanying the drawings, "The proof of the pudding will come in line-plate reductions of the drawings."

There was little delay in putting the work to this final test. Drawing A was sent at once to a good photoengraver with instructions to make a line engraving on copper the actual dimensions of the original die. The plate then was carefully electrotyped and the mounted electro rushed to the printer as soon as Mr. Dwiggins had passed on the engravers proof. He commented in this connection, "The job looks right enough to go ahead with the immediate project without further fussing. Reduces very nicely, I think. It will have slightly more 'color' on book paper, of course."

So the recaptured design of the seal went to press in February 1940. Since 1773 it had been impressed on wax times without number directly from the steel die. But imperfect copies of those impressions had been made and still less faithful copies of the copies had followed. Now it appeared, fresh and clean-cut, in printer's ink.

"On your title page it looks very crisp and knowing," the artist wrote with pardonable satisfaction as soon as the prospectus of the General Catalogue reached him. "The only thing that occurs to me to suggest is to add a tiny bit of black in the form of accents here and there in the stuff around the shield: the figures and the scroll-work—not in the 'irradiated triangle' which is OK. Maybe a little, too, in the cabbage patch, but I am not sure. The point being that the 'color' seems to run a little thin and faded inside the ellipse."

Back went the drawings to the artist for final polishing off. Meanwhile the first state of the reformed seal was circulating among the alumni. When the drawings returned "the sort of mist over the cabbage patch" had been precipitated by a few cunningly placed accents.

From the drawings in their final form the photoengravers made copper line plates ranging from five-eighths of an inch to three and a half inches in height. Deliberately, these were ordered unmounted, so that they could not serve as printing surfaces in themselves but only as models for facsimiles, and after a battery of cuts had been secured they were stored safely away. There is, of course, no pretense that they are replicas of the matriarchal die, but as her legitimate offspring they deserve the best of care.

It is remarkable that since the recovery of the design there has been a growing distaste for the bastard litter of so-called seals which decorate belt buckles, ash trays, note paper, memory book covers and the like. This is an unexpected development: when the Publications Committee set out to get a decent seal for the General Catalogue there was no intention of starting a crusade. There is no present intention of waging war against these monsters that I know of. But it is pleasant to think that there may be enough vitality in the naive old design to sweep the claptrap before it.

In any case the College has its seal once more, to print where it thinks fit. The Publications Committee feels quite happy about it as doubtless do the shades of the trustees of 1773, to say nothing of Nathaniel Hurd.

NEW ENGRAVING OF THE SEALThe seal converted from intaglio torelief printing surface.

WORKING DRAWING FURNISHED BY THE ARTIST, W. A. DWIGGINS, AS MODEL FOR NEW LINE ENGRAVINGS

Trustees record entry, 1773, describing their newly adopted seal, an impression of which is annexed, and photo-graphic enlargement (upper right) of original die from which artist worked.

As SHOWN IN CHASE'S HISTORY

WOODCUT VERSION OF 1869

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ART

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Article

ArticleSocial Idealism in College

December 1941 By ARTHUR E. JENSEN -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1941 By Frank Hall '41 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

December 1941 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919*

December 1941 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR