The Undergraduate Career of Robert O. Blood Jr. Symbolizes Keen Community Interests of Students

MR. SMALL, A FARMER up at North Pompanoosuc, broke his leg the other day. It meant just about the end of farming for him, with all the preparations for a Vermont winter yet to be made. He had no money to hire help, even if men were available, and his neighbors were working day and night themselves. The end of farming for the Smalls meant the end of living; the Smalls had lived on that bit of rocky soil since there had been a farm there.

The word was spread, and a group of neighbors whose path had never crossed that of the Smalls, but who had lived within a few miles of the Smalls for generations, came last Saturday and began the job of tucking in the farm for the winter. Saturday they dug and stored the turnips, beets, carrots, and cabbages; piled thick evergreen branches around the foundation of the house under the careful direction of Mr. Small, for it is an art and must be carefully done to keep the house warm and snug all winter; and began the job of cutting and piling the winter wood. They're coming back Wednesday to finish that job, but they must leave early, for some of them have evening classes. Dartmouth, in a small but significant measure, is returning home, back to the land.

There has been a lot of this going on in the little rural settlements in the back country around Hanover these last two years. The boys help out in all sorts of jams. They may bring in a farmer's crops when his hired man is drafted at harvest time, fence in pastures, repair a barn damaged by fire, or help establish a refugee on an abandoned run-down farm. It is done unobtrusively, so that it makes scarcely a ripple in Hanover. Only the appearance of a notice twice or three times a week in The Dartmouth-. "Social Service Commission: Farm work trip leaving 38 Robinson at 1.15 today," reminds the general community of the work that goes on. The number of work-hours per week, averaging 40 to 50, is, of course, ridiculously small in relation to the number of students in college and to the amount of work that needs to be done, but the results are important, not only for the Smalls, the Deans, or the Shattucks, but for Dartmouth College as an institution.

Over the years we have become a national rather than a local college. To attain certain values we have lost others, not the least of which is a close relationship with the people of the countryside around us, a relationship the College had in its early days, when the students came largely from Vermont and New Hampshire. Dartmouth has fast been losing meaning for the local villages of Vermont and New Hampshire. Certainly there exists many a Dartmouth graduate who has never acquired his share of the spiritual granite of New Hampshire. In order .to train men who will contribute to their community rather than merely reside in it, whether in Timbuctoo or White River Junction, the college should be a living part of its environment. It should have a personality for the people who live in its neighborhood, and it should have a spiritual as well as geographical place in the countryside.

The fact that the Smalls know that Dartmouth boys have an enormous capacity for home-made doughnuts, the fact that for a few hours one fall afternoon Mr. Dean of Etna and six boys worked hard together digging potatoes, the fact that Mr. and Mrs. Stone of Beaver Meadow drove their buggy to Hanover last spring to hear the Glee Club concert because one of the boys had helped roof their barn the week before—these are tenuous bonds anchoring Dartmouth to the community.

When one of the students is asked, as they all sometimes are: "Why are you doing this sort of thing?" he becomes inarticulate. As Bob Blood '42, the chief moving spirit behind these expeditions, tried to explain: "It's more just a reaction to a situation than a philosophy. The work needs to be done, and we feel that we should do it." A little more questioning brings out the fact that the work they do has really a deep meaning and significance for them. From it they get a satisfaction which no athletic contest can give, for it is a satisfaction of spiritual as well as physical needs. They experience on these trips what is one of the greatest pleasures in life for those engaged in mental work—the joy of working at productive physical labor with one's fellow men. They often sing together as they tramp from the fields to the farmhouse. They have the satisfaction of working as a group to achieve a common end in which they can all take pride and which has been a social contribution. They have done something for themselves as well as for other people. They have given help where it was needed. Their conscious motivation is as simple as that, but behind that response one finds the inarticulate realization that the individual must be his brother's keeper, not only for the brother's sake but for his own.

The organization which does the work, the Social Service Commission, has grown steadily since it was first organized in 1939 with Robert O. Blood Jr. of Concord, N. H., as its first chairman. Bob, the son of the present Governor of New Hampshire, came to Dartmouth in 1938, taking premedical work at the start. He is a Senior Fellow, a member of Phi Beta Kappa, besides playing the cello in the Prokofieff Society and working actively in other student groups.

In his first semester of college Bob joined the Dartmouth Christian Union, which was then a pretty moribund organization. Larry Durgin, president of the Union, George Dreher, Bob, and one or two others were soon looking for action. Learning that the Rev. John Harris of the St. Thomas Episcopal church, now of Trinity church, Boston, often put on dungarees and went into the countryside to give practical assistance to farmers in need, they joined him on one of his trips. They sweated at the unaccustomed labor of clearing a field for a farmer who was ill, and at the end of the day were tired and stiff, but unaccountably happy. At their next meeting Bob suggested that the Union undertake this sort of field work as part of its program and was made chairman of the Field Work Committee of the Dartmouth Christian Union. This committee was before long the tail that wagged the dog, and was soon rechristened the Social Service Commission.

The Social Service Commission which began in the fall of 1939 with eight or ten men, put in a minimum total of 400 man hours of work, even though they did no active field work from December to April. During the winter months they undertook at the request of the Red Cross a social survey, gathering and coordinating information on needy cases in the neighborhood of Dartmouth. In this way they got to know at first hand the immediate needs of the country people and how the Social Service Commission might most effectively help them. Consequently when spring came around they began the field work again with even greater enthusiasm and more intelligent understanding.

Last year, Bob Blood's junior year, the idea spread without any fanfare of publicity, and a total of 90 undergraduates took at least occasional part. There was at least one trip every week College was in session, usually two, often three, and this year the progress is continuing. There is a minimum of administrative machinery. When the boys hear, usually from a local minister, that Mr. Small has broken his leg with his winter fuel uncut, the word goes out, and at 1.15 in the afternoon from two to 18 boys pile into cars, usually borrowed, with tools assembled ready for work. It is as direct and unassuming as that.

It is not merely the fun of productive physical work which brings the boys out to saw wood on a bitter winter day. Nor is it merely the pleasure of "doing good." The work is, in some cases consciously, in most cases unconsciously, one of the many ways in which the undergraduate generation is solving the problem of how to live with honor and self respect in the present world while still retaining the sensitiveness and enjoyment of life which is their natural right. Bob Blood's solution of the personal problem which faces every young man and woman today and the path by which he has arrived at that solution are not acceptable to most people, but they are valuable as the studied conclusions of a young man of good will with a first class mind.

HOLDS SENIOR FELLOWSHIP

Through the Social Service Commission Bob became interested in the larger work of the Society of Friends, an interest which finally led to his joining the Society last September. The decision, of course, was not merely one of formal religious affiliation but one which vitally affected all aspects of his life. This summer at Pendle Hill, a small graduate school conducted by members of the Friends, he did special work in a course in the concept and history of the non-violent movement. Meanwhile, at Dartmouth, after three years of brilliant work in pre-medical study he has dropped medicine, and this year, as a Senior Fellow, he is working intensively lii the Social Sciences so that after he has taken his degree he may join the American Friends' Service Committee. A few young men from that Committee are now at Geneva studying the languages and cultures of the European peoples thJy hope to serve. They are the spearhead of others to come from the United States, who will, as soon as peace makes it possible, plunge into the work of physical and spiritual reconstruction. Through helping refugees, through founding work camps on the model of those the Friends have already established here, through setting up soupkitchens, and by other means, they plan to work untiringly for the reconciliation of peoples and for a decent international organization. Bob hopes to be sent abroad for that work; he is content, however, to go where he is sent, which will be where the central committee thinks he is most needed. He has discovered for himself the concept of the brotherhood of man, and idea and action have fused.

Some of the others in that closely knit fellowship, The Social Service Commission, cannot accept all his ideas, but on the immediate task in Hanover they are united, and the ideas and functions of the Commission are on the way to becoming an integral part of Dartmouth life. Similar groups are springing up in other colleges. Last March when the New England Community Relations Commission held a conference at Dartmouth, of which Bob was co-chairman, over 80 delegates attended. From a generation of men who are too young to have known any period but depression, pre-war, and war, there is coming a leaven of men who may go far toward revitalizing and advancing a civilized democracy. Many of us disagree with some of the fundamental tenets, but the very existence of idealism in the college generation, an idealism, moreover, that is practical and is being turned to immediate and palpable results in the world of today rather than in the mystic regions of when-and-if, is a very bright candle in the dark for the older generations.

Bob is not typical of anything; nor is he exceptional in kind—at least not so much so that he is "different" or "queer"though perhaps his development at Dartmouth, the scope and direction of his activities, are exceptional in degree in the present college. He is one of the rapidly growing group of socially minded students.

When we despair of the seeming inadequacy of the younger generation for the great role in history that has been thrust upon them we are forgetting their place in past history. Born with the bitter taste of post-war disillusionment in their mouths, their childhood spent in the hectic '20s, their boyhood in the depressed and confused '30s, they arrive at manhood to find a ready made war which, in all probability, they will have to fight. Still dazed as they are, they must move. Their passions are not ours, but it is safe to say that no recent college generation has had a larger proportion of practical idealists. Certainly those of us who have vivid recollections of the student world of the '20s realize that in that period Bob Blood and his ideas would have been freakish. Today we accept him and the Social Service Commission as normal ingredients in the undergraduate ferment.

Bob, in fact, is an illustration of a basic shift that has taken place in the aspirations and thoughts of undergraduates in the course of two decades. The spirit of the undergraduates and their end goals today are different from what they were in the '20s, when students were inevitably affected by the flavor and general morale of that exciting decade. Students then came to college in the backwash of World War I and at a time when Prohibition gave the glamor of vice to silliness. It was a decade of what may have been the last brilliant flare-up of American individualism and materialism. The business man and the banker basked in profits and prestige. Americans as a group were conscious or sub-conscious escapists from the necessity of making profound moral choices, and the material prosperity of the decade enabled them to exalt values we now recognize as unworthy of responsible human beings.

' * o The spirit of the time was inevitably translated into the colleges. The distinctly over-ripe tone of local and national politics was reflected in fraternity politics on the campus. That the business of America was business was accepted with little question, and college men looked forw ard to careers in Wall Street or in some lucrative business. The idealist, both in society and in college, reacted sharply, but by and large the course he followed was to condemn and escape, rather to condemn and attempt reform. Intellectuals and artists left the America where George F. Babbitt was king, holding their nostrils, and took refuge on the left bank of the Seine. In college, the sensitive idealistic intellectual became a follower of cults, a devotee of art for art's sake, and in his own way as thorough an escapist as the brethren he considered so benighted.

That world, that society, and that college spirit disappeared after the fall of 1929. Since then the shift of values among college men has kept pace with the shift in the world outside. Those of us who have been so fortunate as to have had daily contact with undergraduates over the last fifteen years have noticed a steady growth of social consciousness. We have noticed a larger and larger proportion of undergraduates preparing for government service rather than for business. We have noticed that adolescent idealism, so prominent in college years, has become more and more practical, more and more concerned with the -world as it is, and with the alleviation of actual conditions rather than with an escape into the pursuit of an unattainable absolute. The undergraduate is the same as he was in the '20s—the same as he has always been. But the world is different. The drives of the class of 1942 are those of the class of 1922, but the pressure of the world in which the men live, and a possible world in which they and their children will live, has directed those drives into far different channels, with far different results.

Bob Blood and his group are symptoms of the change which has already taken place. They are also ingredients in the inevitably greater changes to come. This group, and the men who will follow them in college and out, have responded to the difficult job they have to do—the job of living in the world today with honor, sen- sitiveness, and good-will, and of making sure the job is not rendered impossible for future generations—with a social idealism which may well go far toward making democracy work in America and the world.

ROBERT O. BLOOD '42 FOUNDER OF STUDENT SOCIAL SERVICE COMMISSION

ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

THIS IS THE THIRD in a series of descriptive articles about leaders in the undergraduate body whoare setting high standards in thebranches of student life in whichthey are prominent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

December 1941 By Frank Hall '41 -

Article

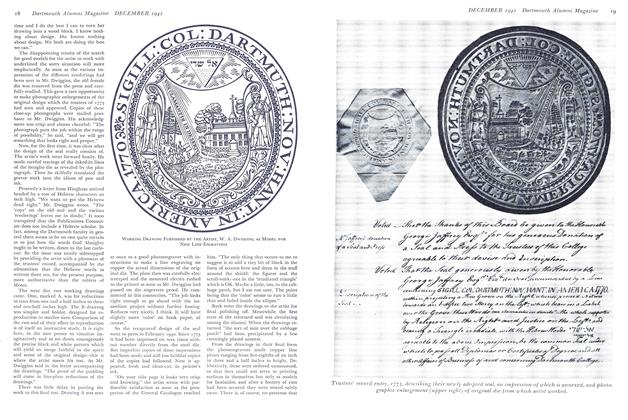

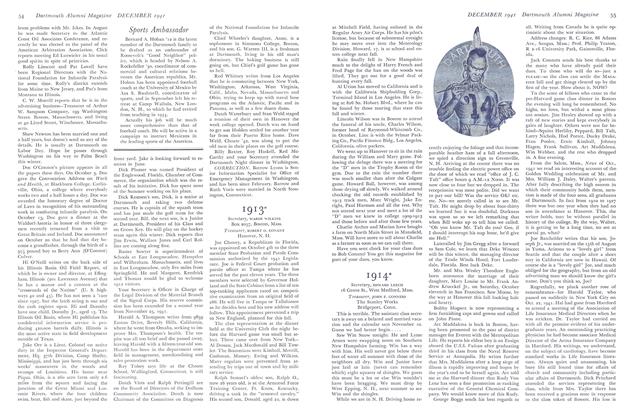

ArticleRediscovering the College Seal

December 1941 By RAY NASH -

Class Notes

Class Notes1937*

December 1941 By DONALD C. MCKINLAY, ARTHUR H. RUGGLES JR. -

Class Notes

Class Notes1912*

December 1941 By CONRAD E. SNOW, RICHARD C. PLUMER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1919*

December 1941 By WINDSOR C. BATCHELDER, MAX A. NORTON -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918*

December 1941 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, DONALD L. BARR

ARTHUR E. JENSEN

Article

-

Article

ArticleTO COMPLETED SERVICE

April 1934 -

Article

ArticleDCAC "Football News"

MAY 1957 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES DARTMOUTH OUT OF DOORS IN THE EIGHTIES

January 1924 By Charles Sumner Cook '79 -

Article

ArticleHanover Browsing

October 1940 By HERBERT F. WEST '22 -

Article

ArticleHow to Fix the Fed

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2014 By Peter Fisher -

Article

ArticleExercising the Mind

MARCH 1999 By Rich Barlow '81